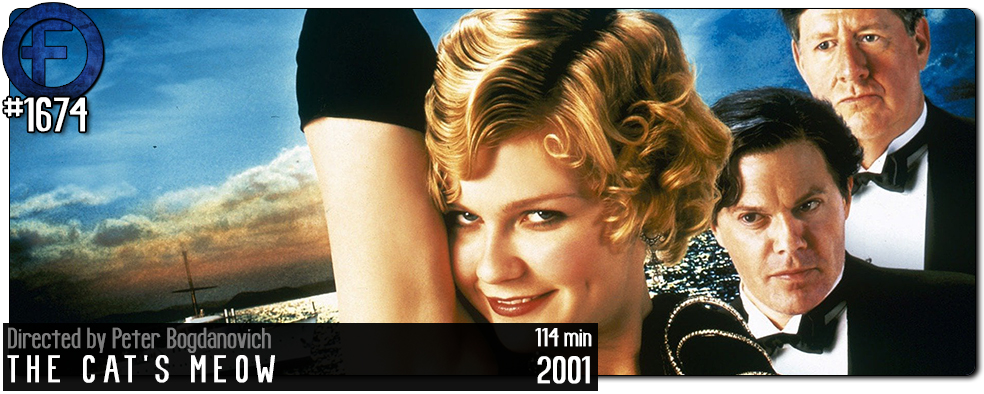

Movie Review – Cat’s Meow, The (2001)

Principal Cast : Kirsten Dunst, Carey Elwes, Eddie Izzard, Edward Hermann, Joanna Lumley, Jennifer Tilly, Claudia Harrison, James Laurenson, Ronan Vibert, John C Vennema, Ingrid Lacey, Victor Slezak, Chiara Schoras, Claudie Blakley, Steven Peros.

Synopsis: Semi-true story of the Hollywood murder that occurred at a star-studded gathering aboard William Randolph Hearst’s yacht in 1924.

********

If there’s one thing Hollywood loves, its movies about itself. Films about cinema – particularly the early years of Hollywood – are almost always entertaining in some manner, and The Cat’s Meow is no different, despite a darker undercurrent running beneath its glitzy exterior. Based on a scandalous story from the 1920’s, in which Hollywood cowboy picture producer Thomas Ince was mysteriously killed during a party aboard the luxury yacht of newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst, The Cat’s Meow suffers from an indignity of terrific casting and a truly delectable screenplay, only to come undone by a bizarre stiffness to the production that undercuts the joy and shallow frivolousness of the people involved. The likes of Charlie Chaplin – then one of the world’s biggest screen stars – and Elinor Glynn, one of the more salacious novelists of her era, alongside the blustering Hearst (himself the subject of a film, tangentially the core of Citizen Kane) and aspiring actress Margaret Livingston (who would be seen in Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans), collide in a frenzy of decadence, subterfuge and death; the film isn’t up to the task of making us enjoy the story, but the story itself is enough to make me enjoy the film anyway.

November 1924, and a gaggle of Hollywood movers-and-shakers board the “Oneida”, a luxury yacht owned by publishing magnate William Randolph Hearst (Edward Hermann) and his mistress, Marion Davies (Kirsten Dunst), for a celebratory birthday party for Hollywood producer Thomas H Ince (Carey Elwes), who has stumbled upon financial difficulty and is using the occasion to cosy up to Hearst and possibly gain a business partner. Also aboard is Charlie Chaplin (Eddie Izzard), currently scandalised by making his teenage co-star, Lita Grey in The Kid pregnant, as well as the largely unsuccessful reception of A Woman Of Paris, and whom is deeply infatuated with Davies himself, romance novelist Elinor Glyn (Joanna Lumley), aspiring journalist Louella Parsons (Jennifer Tilly), and aspiring actress Margaret Livingston (Claudie Harrison), herself the mistress of Ince. As the boat trip goes on, Hearst is increasingly paranoid over his mistress’ affection for Chaplin, despite her protestations to the negative, and Chaplin’s flirtations don’t exactly go unnoticed. It all leads to a violent confrontation that will test the very nature of Hollywood’s power structure.

Directed by Peter Bogdanovich, the story behind The Cat’s Meow is infinitely more interesting than the film itself, and the film itself is pretty good. Bogdanovich, who interviewed a number of key names around this story over his lifetime (including Orson Welles, who refused to openly divulge what he knew), remains perhaps the most knowledgeable person to tell this salacious fable, a story of death and betrayal, of power and corruption, a story Hollywood itself is loathe to probe too deeply. It’s the kind of story whispered around backrooms and hush-hushed from public knowledge, a scandal so enormous it threatened to ruin entire careers; only, the death of Thomas Ince was barely a footnote in history, his fate (allegedly) squashed by the influence and power of William Randolph Hearst, who apparently shot the man by mistake after thinking him to be Chaplin, the latter supposedly having an affair with Davies. The truth is we’ll probably never know the real story, or the exact events of that fateful day aboard the “Onedia”, mainly because the investigation consisted of only a single person being questioned in relation to Ince’s demise, and his death being ruled as “natural causes”. Speculation continues to this day, and the clues around the story of his death seem to point to foul play and an apparent code of silence from guests aboard the yacht keeping mum on the truth; Bogdanovich, working from a screenplay by Steven Peros based on his own play of the same title, happily concludes that Ince was killed by an act of “accidental murder”, a crime of passion, if you will. Whether this works for you or sullies people’s good names (Chaplin, a key figure in the affair, was notable for the various scandals that plagued his career and life) isn’t so much the question as it is a statement of fact. The gall of Bogdanovich to use the “this film and the people depicted herein are entirely fictitious….” tag in the film’s credits is gobsmacking, given the film is entirely filled with real people, despite some fudging of their personalities to suit the story and its largess.

The Cat’s Meow is a delight of wit and charm, a film of patter-dialogue and banter torn right from classic Hollywood films of the era. There’s an effervescence to the ensemble’s work here, a charming sense of theatricality to the way the film intercuts between characters and events, and Bogdanovich balances the arcs of each of the participants with ease. Nobody in the film feels shortchanged for screen-time, although it’s quite obvious who the focus is (and should be) on. As Hearst, Edward Hermann’s commanding, bellicose performance rattles along brilliantly, and his chemistry with on-screen consort Kirsten Dunst, as Marion Davies, is actually really sweet (given their age gap, it should have been creepy as hell, but it isn’t) and for her part Dunst is excellent in the role of the bubbly, flirtatious muse. Carey Elwes exudes the charm and manic perseverance required to bring Thomas Ince (back) to life. The Hollywood producer was apparently something of a giant in the early days of American cinema, presiding over the ubiquitous cowboy film and turning his production shingle into a factory-style film-making enterprise that would change the industry. Sadly, his name somewhat faded after his death, and as mentioned he’s barely a footnote in the annals of Hollywood today, even though he produced countless Westerns for the genre. Elwes sports that dapper gent tone and glib-tongued rapaciousness to readily he’s actually creepy. Eddie Izzard brings a playful wretchedness to Charlie Chaplin that was absent in Robert Downey Jr’s essaying of the same man, and for the life of me I can’t help but wonder how Izzard never became a bigger star. He effortlessly encapsulates the tragic figure of the tortured comedian. Watching the likes of Joanna Lumley and Claudia Harrison clash wildly with Jennifer Tilly’s coarse Louella Parsons is a hoot, and the vapidness of the entire coagulation of Hollywood names aboard the yacht is delightfully pernicious.

While it certainly tickled my fancy, The Cat’s Meow probably won’t entice casual viewers into its charms. It’s a film in which a cursory understanding of who everyone is, and the specific time in their lives, is important, because it plays heavily into motive. Chaplin’s career was at a crossroads creatively: A Woman Of Paris was not well received on debut, because he wasn’t in it (a fact repeated often in this film), and his follow-up film, The Gold Rush, was massively over budget and plagued by production problems. Davies, Hearst’s long-time companion, felt stuck in dreary dramatic roles when all she wanted to do was appear in comedy, something Hearst was against because it demeaned her talent. Glyn, for her part, maintained an air of sophistication around the vacant-eyed Hollywood elite, partying to accentuate her lustre as an erotic novelist. And Louella Parsons: of all the people involved in the incident, it would be her who should benefit the most. Portrayed by Tilly as a loudmouthed social ignorant, Parsons parlayed a career with Hearst’s newspaper company that would see her become the foremost gossip columnist in the United States, and certainly one of the most influential people in Hollywood. Silence pays its own way, if you believe The Cat’s Meow.

With it’s jazzy 1920’s musical soundtrack, and captivating cinematography by the acclaimed Bruno Delbonnel, The Cat’s Meow certainly plays well within its period-piece wheelhouse. The costuming and production design aboard the yacht, where the film almost exclusively takes place, is first rate, a loving throwback to the freewheeling decade of decadence following the conclusion of the Great War. The film is really well edited, something I came to appreciate when handling such an expansive cast of characters in such a confined locale, and Bogdanovich’s framing and style here reminded me of Woody Allen’s style, restrained and letting the actors do all the work. The film is driven by dialogue almost to a fault, lacking any real action other than the climactic death of Thomas Ince, and Bogdanovich uses his camera to infiltrate the story vicariously, subtly, rather than ostentatiously. It’s like the frenzied bits of Luhrmann’s The Great Gatsby viewed through a prism of morphine, slowed down and given time to breathe. That said, the film sputters here and there, lacks conviction in its own temperate nonchalance of tone, grinding to a halt at times before springing to life again quite quickly. The various subplots work well enough together, although the crux of the film – Chaplin’s infatuation with Marion, and Hearst’s paranoia over their affair – hedges its bets a little too often for my liking.

If you’re a fan of Hollywood’s history then The Cat’s Meow is a film you’ll enjoy. It’s not exactly a showstopper, however, and if you’re unaware of who all the people are in the film then you’ll probably spend a lot of it quite confused, but on the whole the film delivers some delightful dialogue and winning performances from an eclectic and dynamic cast, even if at times the film seems strangely inert. Hermann is wonderful, Dunst is great, Izzard delivers far more than I expected, Elwes struts like a peacock, and everyone else is up to the challenge. Well shot and edited, and given its snappy, finger-clicking soundtrack there’s few cinema aficionados who won’t find The Cat’s Meow at the very least an interesting glimpse into a story buried deep in Hollywood’s history and hidden by shadows.