Movie Review – Nosferatu: Symphony Of Horror

Principal Cast : Max Schreck, Gustav von Wangenheim, Greta Schroder, Alexander Granach, Georg H Schnell, Ruth Landschoff, John Gottwot, Gustav Botz.

Synopsis: Vampire Count Orlok expresses interest in a new residence and real estate agent Hutter’s wife.

*******

The early days of cinema were something akin to the Wild West; a distinct lack of concern over things like copyright, for example, would come back to haunt Nosferatu, since director FW Murnau openly admitted to basing his film on Bram Stoker’s famous novel “Dracula,” albeit with names changed and some minor plot details removed. We’re lucky to have Nosferatu at all, really: Stoker’s estate sued the film studio and won, and was ordered to have all prints destroyed. Luckily, some international prints survived the cull, meaning Murnau’s vision of horror remains intact and enjoyable to this very day. Considered chief among the definitive vampire films ever made, Nosferatu’s legacy is entrenched in the genre – well before vampire’s sparkled, or even before they became debonair, charismatic men of allure, Nosferatu’s depiction of Count Orlok, the titular monster, was that of deformity and hideousness.

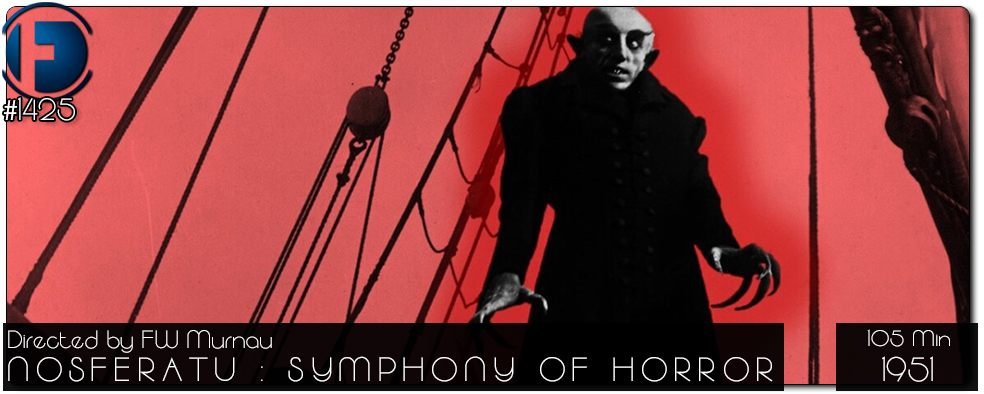

For me, the vampire film that defined my cinematic love of the genre was Coppola’s Dracula, starring Gary Oldman and Keanu Reeves. It was apocryphal, faithful, and utterly astounding in its use of the visual medium to accomplish some (still) sublime moments of genuine gothic horror. Within Nosferatu, a film that arrived some 70 years prior, one can see the genetic material Coppola would utilise in his own depiction of the classic horror creation. Personified by an utterly creepy Max Schreck, the central vampire character – here referred to as Count Orlok, rather than Dracula – is hideous and malformed, a literal walking corpse with garish eyes and skeletal limbs, a vertiginous slenderman of nightmarish countenance who commands the screen whenever he’s on it. As any good rip-off is wont to do, Murnau’s film follows Stoker’s original story quite closely, only changing the names and places from the literary text in order to skirt outright adaptation. Using a fairly bright colour palette, Murnau manages to bring a wonderful sense of menace and underlying sinister tones to a film tinted alternately in gold, blue, aqua and monochrome, extracting the frisson of terror audiences came to enjoy.

“Nosteratu: does not this word sound like the call of the death bird at midnight? Take care you never utter it, lest life’s pictures fade into pale shadows, and ghostly dreams rise from your heart and feed on your blood.” – Opening text.

Synopsis: The European town of Wisborg: young property manager Thomas Hutter (Gustav von Wangenheim) is sent by his scabrous employer, Knock (Alexander Granach) to obtain the business of a mysterious Count Orlok (Schreck) in renting a local property. Hutter leaves his wife, Ellen (Great Schroder) to travel to the far off Carpathian Mountain estate of Orlok, where the young man discovers his client is actually a hideous coffin-dwelling creature of the night; Hutter obtains Orlok’s signature, only to discover the man has rented the house immediately opposite his own back in town, in order to be closer to Ellen. Local professor, Bulwer (John Gottowt) offer up his knowledge on vampirism through his class, and as he is made aware of Orlok’s arrival in Wisborg, becomes engaged to hunt down and destroy the sinister creature.

German film director FW Murnau was a creative force unlike any other working in the film industry during the early 20th Century. Nosferatu is perhaps his most revered film, although it certainly isn’t his most accomplished – to wit, Sunrise remains the best of his films I’ve reviewed on this site thus far. Murnau’s sense of style and command of the mise-en-scène is demonstrably his strongest aspect, and as with both Sunrise and (to a lesser extent) Tabu, his 1922 horror film Nosferatu is indicative of an unwavering creative flair. While Nosferatu is a grand exponent of Murnau’s early output (much of his material prior to Nosferatu has been lost, unfortunately), there’s a sense of exploratory gamesmanship with the viewer here that I really enjoyed. The film isn’t polished in the sense of its technical skill, nor is it particularly “horrific” in the manner of its later genre brethren, but what it does do is hone in on Murnau’s exceptional skill with framing and his dynamite editorial vernacular, and play up the strengths of it memorable cast – especially Schreck and Granach, playing the derivative Dracula and Renfield from the Stoker text respectively.

Modern proponents of vampire lore have given the blood-sucking monsters a sense of primal sexuality and “hotness”, for want of a better word. You might argue that Anne Rice’s playful sensuality with the vampire, personified in the Tom Cruise film Interview With A Vampire, paved the way for a softening of the monster that inhabited the darkened bell-towers of our collective minds, to its detriment. The sparkly Twilight saga only magnified the millennial equivocation with which we romanticised the immortal life led drinking blood, through Edward Cullen and his beautiful beau Bella and their insipid, crushing romance. Vampires are inherently abhorrent, monstrous creatures by definition; stoked by history and affluent tragedy (Dracula was once an aristocratic member of Transylvanian society before succumbing to the dark pact he made with the devil), modernity has de-fanged them to the point they’re no longer truly evil.

Stoker’s Dracula isn’t a creature of sympathy, but rather a manifestation of selfishness and base desire; Murnau recognised this in the author’s work, and imbues his Count Orlok with a similar romantic mendacity. Orlock is an apex predator, albeit one hindered by sunlight (curse you, undead flesh!) and he behaves like a shark circling its prey, stalking both Hutter and Ellen and all the sailors aboard the vessel he voyages from Transylvania to Wisborg on. Orlok is a creature to be feared, and Murnau generates this not only through stark high-contrast photography but through Schreck’s creepy, eerie performance, enabled as he is through some tremendously effective makeup.

One of the more surprising elements to Nosferatu is how bright the film is. Unlike most modern horror films, darkness appears not to be an ally of Murnau’s production. Much of the film is shot in broad daylight, making suspense through shadow feel less like a feature and more a technical limitation. Instead, Murnau gives the film its skin-pricking sense of dread through trick photography and the cast’s performance rather than a specific visual motif. Despite its 1922 limitations, Nosferatu is also surprisingly epic, shooting on atmospheric locations through Germany and Slovakia that give the film a real feeling of scope. The soundstage sets do feel a touch flimsy compared to their bricks-n-mortal exterior counterparts, but Murnau wisely uses a lot of different angles to hide this element of his film. While not the resplendent masterpiece of visual daring that Sunrise was, Nosferatu has its own unique charm that elicits enough chills to maximise the thin story’s efforts.

If anything, Nosferatu’s writer, Henrick Gleen, is to either be commended for simplifying Stoker’s story enough to give us a 90 minute film, or blamed for simplifying it so much it’s actually rather boring. Anyone who has ever watched a version of Dracula will find each beat of the story play out in a speedily condensed fashion, casting aside careful narrative tension for brevity and superficial entertainment. Indeed, Nosferatu isn’t particularly deep thematically, despite the sonorous (and often amusingly cliched) interstitials that punctuate the movie. Nosferatu is a film that benefits substantially from its location filming rather than its writing, and this benefit if only exemplified by Murnau’s visual coherence rather than Gleen’s screenplay. Apparently Murnau also rewrote a significant portion of the film’s final reel, although you can’t really tell.

It’s easy to see why Murnau’s Nosferatu is considered the cinematic vampire game-changer it is today, its determined style and perfectly sunny disposition notwithstanding. Schreck’s Orlok is definitively creepy, the film’s production values superb, and the supporting cast all delivering charismatic and career-defining performances. Murnau’s use of the camera isn’t particularly exciting but he maximises the story’s inherent menace and underlying terror with acutely deft touches of screen magic, and even when the story stagnates in the second half, he cannily keeps things moving at a brisk enough pace to keep the audience interested. The template by which all other vampire films are measured (and only very few equal for sense of iconography), Nosferatu is interesting if not outstanding, and although today it might be considered cliched, at the time delivered requisite chills enough to test even the hardest audience member’s mettle.

All these years later, I still remember watching Nosferatu. In college, an independent theater was showing a double feature of Nosferatu (with live piano accompaniment), and the 2000 film Shadow of the Vampire. It was a fun night out, for sure. I remember Nosferatu had great atmosphere and cinematography, but a really weak story. Pretty much exactly what you described. Man, I haven’t thought of that in years. Thanks for the trip down memory lane.

Nosferatu and Shadow Of The Vampire have special place in my heart simply for the fact that Shadow was the last film I watched prior to the television coverage of 9/11. We switched off that film (on VHS, no less) and back to the TV just in time to see the first tower collapse. Suffice to say, both Shadow and Nosferatu (which we’d watched earlier that afternoon, Australian time) remain indelibly linked with that awful day.

That said, the pure inventiveness and visual strength of the film mitigates an otherwise weak story, which I found surprising considering the source material. I’m glad I could bring back some fond memories.