Movie Review – Napoléon

Director : Abel Gance

Year Of Release : 1927 (2000/04 Brownlow Remastered Edition)

Principal Cast : Albert Dieudonne, Edmond van Daele, Alexandre Koubitzky, Antonin Artaud, Abel Gance, Gina Manes, Marguerite Gance, Yvette Dieudonne, Phillipe Herriat, Max Maxudian, Annabella, Nicolas Koline, Maurice Schutz, Andree Standart, Suzy Vernon, Petit Vidal, Francine Mussey, Robert Vidalin, and Vladimir Roudenko.

Approx Running Time : 5 Hours, 33 Minutes

Synopsis: A film about the napoleon Bonaparte’s youth and early military career.

*****

Master director Alfred Hitchcock once said “The length of a film should be directly related to the endurance of the human bladder.” I’m more keen to popularise my own quote that says a film shouldn’t run any longer than the story it’s trying to tell, regardless of length. Approaching Abel Gance’s 1927 epic Napoleon, an endurance test of a film running a touch over 5 and a half hours, one has to consider both the subject matter and the man making it, both of whom have become French iconic in their own right. Depicting the early life of the famous French military legend, Napoleon Bonaparte, Gance’s astonishing romanticised biographical masterpiece contains some electrifying cinematic invention, a dash of convention, and an altogether enthralling montage of imagery that delights as often as it astounds. I guess one might argue that a man of such mythic stature as Napoleon would warrant an equally epic film, and allowing for creative license and contracted time settings, as a potted-history (and virtuously patriotic) depiction of his early life, the film is an astonishing feat of compelling creative virtuosity.

It’s worth noting that the film’s current marathon running time is dwarfed by Gance’s own “Definitive Version” released in 1927 (re-edited from the theatrical release), which ran out to a staggering 9 hours and 22 minutes; our review of Napoleon is based on the 2000 reconstruction by Kevin Brownlow (and its subsequent 2004 remastering into HD formats) of available footage, some of which had been lost for many years. A further sidebar; apparently Gance envisioned a six-film saga about the life of Bonaparte, up to his death on Saint Helena, however following extensive costs and problems making this film, the burden of making more was prohibitive indeed.

Expansive, often brilliant, occasionally melodramatic to a fault, and always enthralling, Abel Gance’s Napoleon is a virtuously patriotic depiction of one of history’s most enduring figures. My knowledge of French history, more specifically around Bonaparte’s life and his actions through the Revolution, are cursory at best and tempered with the knowledge of Bill & Ted’s Excellent Adventure, I approached Napoleon with my Wiki-fingers at the ready to follow the story and glean an understanding of the players within it. Suffice to say, Napoleon touches a lot of the man’s life, from his early childhood in a harsh, puritanical school in Brienne-le-Château – here, played as a young boy by Vladimir Roudenko, who looks like an ancestor of Elijah Wood – through to his early militaristic leanings and fervent desire to see France remain allied with itself rather than with England, as well as his great love of Josephine (Gina Manes), the aristocrat who would become his wife, and the embodiment of his messianic rise through military ranks to become the great General we all know.

The adult Napoleon is played by Albert Dieudonne, whose visage is a close approximation of the real historical figure, and he absolutely gives the role his all. Dieudonne personifies Napoleon’s fierceness of temperament and stoicism of patriotic endeavour: Bonaparte’s ferocious zeal in protecting his French lineage – a proud Corsican throughout – is highlighted by his cavalier adventures outrunning a variety of pursuing adversaries, all of whom saw him as something of a terrorist or usurper who needed to be killed off. Dieudonne’s performance is actually rather inauspiciously un-emotional, at least in terms of connecting with the viewer, simply because the film’s epic narrative cycles through segmented elements of Napoleon’s life is played so broadly, although the actor is given range to convey both his piercing hostility to subordinates and infatuation with the women in his life. In one scene, Bonaparte actually stares down an advancing lynch mob, incited by Count Carlo di Borgo (Acho Chakatouny), utterly silent; much of the film dwells on Bonaparte’s status as an icon of world history and the film never flinches in portraying him as an early cinematic superhero. Under artillery fire, he barely flinches, standing solid whilst others flee and cower. He’s without flaw, this Napoleon, and whether accurate or not at least the film doesn’t pull its punches in establishing how his tale will be told. Sidebar: Napoleon is typically depicted as a hot-tempered, short firebrand, almost dwarfish at times, although in reality he stood a practically average 5’6″, about the same height as an ordinary man – his short stature appears to have stemmed from his later stage demand that his elite guard all be over 6 foot.

“Impossible is not French” – Napoleon

Characters enter and leave the film on a whim, dictated largely by Napoleon’s interaction with them throughout his life. Gance, who wrote the film’s screenplay (as well as produced, and edited later versions – the original theatrical version in 1927 was edited by acclaimed French film editor Marguerite Beauge) commands a cast of actual thousands throughout, from large-scale political machination sequences in giant halls, to galloping soldiers and a vast array of military might in the film’s famous triptych finale, and are effective in small ways without protruding into the work of Dieudonne egregiously. The cast are there to support Gance’s focus on Bonaparte himself, means to an end without feeling compulsory or perfunctory. An early scene introduces Revolutionary celebrity Maximilien Robespierre (Edmund van Daele) in one of the most bass-ass establishing shots I’ve seen in silent film – the man, bespectacled, seems to glare at the camera before slowly sliding his glasses off as if to say “what the actual fuck do you want?” with disdain. It’s absolutely awesome. Gance’s camera approaches each sequences subject matter and key players with similar theatricality, giving us interstitial cards followed by lengthy mid-range shots of the character, before continuing with the story.

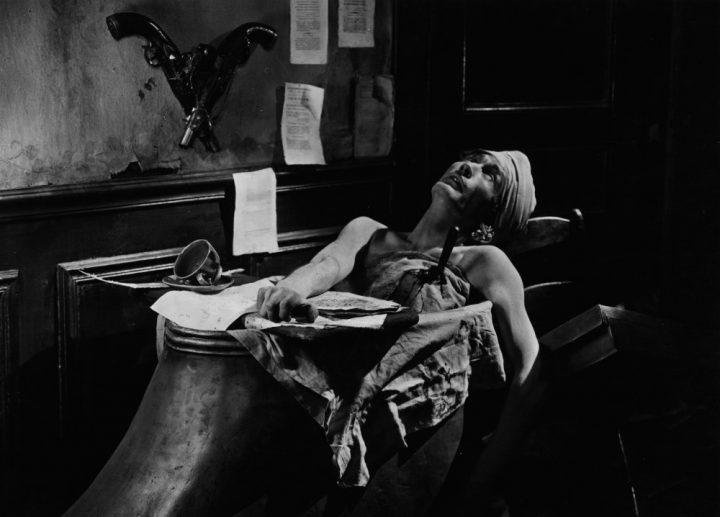

Intertwined with Napoleon’s story are key figures in the French Revolution. Notably, youthful assassin Charlotte Corday, who despised a Liberal-Conservative group known as Girondins (I had to Google them, as I’d never heard of them) and one of their major exponents in Jean-Paul Marat, who she would kill before being beheaded at the guillotine for her crime. Corday is played by Gance’s second wife Marguerite, a fanciful bit of nepotism, but the scene in which she assassinates Marat (Antonin Artaud) works beautifully as a staged piece of historical fact. French actress Annabella (Bastille Day – 1933, Bridal Suite – 1939, Tonight We Raid Calais – 1943) plays the possibly fictional figure of Violine, who harbours a love for Napoleon that’s as unrequited as it is inappropriate. Phillippe Heriat plays Napoleon’s arch rival Antoine Scaliceti, who curries favour with Terror figures (including Robespierre) to bring down Napoleon by surreptitious means, before moving on to more overt methods. Director Gance plays a role in the film himself, as Louie de Saint-Just, a friend of Robespierre and a leading figure in the Reign of Terror.

One recurring motif throughout the film is that of an eagle; during the film’s early childhood sequences, Napoleon curries favour with a pet at the school, and establishes a bond with the symbolism the creature provides. Gance uses this eagle motif throughout the film, particularly whenever Bonaparte is challenged by authority or personal circumstance, almost as a touchstone to his Christ-like status within the narrative. Idealised almost beyond realism, Gance’s Bonaparte is the kind of hero to the French people that is representative of the overt nationalism we see across the globe even today. Some would denounce Bonaparte as an anarchist today; but the film’s salutation of his life and achievement almost always points to authority figures as evil and bad. Getting past this simplistic style isn’t so much a problem as it is weirdly nostalgic, a throwback to a type of cinematic hubris so prevalent throughout much of post-war society of the era.

Regardless of story or character, though, the chief brilliance of Napoleon is its technical prowess. Gance’s direction could be described as that of a virtuoso and an visionary, casting aside convention and creating a film that doesn’t just depict the life of France’s greatest commander, but inhabit it utterly. No doubt monstrously expensive for its day, among the first thing to note about the film is its astonishing costume and overall production design, which looks to have been a no-expense-spared affair. Whether it’s the beer-halls of Corsica or the battlefields of France, the film is brilliantly mounted in every regard; the hundreds and thousands of extras look splendid in costume, whilst the location photography (and there’s a lot of that) is equally widescreen and beautiful. Secondly, the film is a non-stop barrage of just about every type of filmmaking technique you could name, including dolly tracking shots (films of the era were predominantly locked off static shots), POV shots, hand-held action footage, rapid-fire cutting, superimposition, split screen (as depicted by its three-camera triptych finale), and colour tinting, to name but a few. Naval battles are achieved using models in the same vein as Ben Hur’s famous slave-ship sequences. Napoleon is an astonishingly inventive production, with Gance using every trick in the book to throw the audience into the character’s story as best he can. I guess if your film is a bowel-testing five hours and change, you’ve got to keep people’s attention somehow. Napoleon is to silent film what Berlioz was to Romantic period musical composition. Often, it’s euphoric.

“He’s a man of strength, this Bonaparte, just what we lack in Paris” – Jacques François Dugommier

Napoleon is a delightfully creative film. It staggered me just how masterful Gance’s work here is. His use of titles, his use of framing and inter-cutting, his ability to generate tension through instantly iconic shots (like rain-swept battlefields, or Napoleon’s storm-bound boat journey, or the bloody insurrection on August 10, 1792, in which a soldier is hanged, to say nothing of the aforementioned Robespierre introduction) is second to none. Although I was following the story with Gance’s own notes at my side, so I could understand what it was I was seeing on the screen, had I not I would have been just as astonished by what Gance puts on the screen. Blue and orange tints elicit nighttime or daylight respectively, whilst moments of “anger”, such as battle or human rage, are tinted red (obviously). Corday’s assassination of Marat is given a brilliant green hue, whilst some more sedate moments are produced in brilliant monochrome. A “Victim’s Ball” sequence in the third act (apart from being quite racy) is hued entirely in overexposed pink – and includes nudity, so beware, prudes! The national French colours of red, white and blue are used to great effect in several scenes, whilst the score by UK composer Carl Davis, written in 1980 and re-orchestrated for the film’s recent home video release, belts out the anthem La Marsiellaise periodically, as well as accompanying gunfire, cannon-fire and other virtual visual audio cues with timpanic percussion that hammers home the point.

Napoleon is of significant historical note thanks to its concluding triptych sequence, using a system pre-dating Cinerama technology but basically being the exact same thing, albeit slightly less advanced. Filming sequences with three interlocked cameras, Gance could produce a true widescreen image that would heighten the climax of the film’s final reel. It’s an effect that works well considering the film’s vintage, but by today’s standards is clunky, almost awkwardly out-of-place considering the quality of that which immediately preceded it. If a film is to be defined by a single element, then there’s worse that could be thrust upon Napoleon than the invention of an entirely new way of storytelling.

“From this morning, I am the Revolution.” – Napoleon Bonaparte

Conclusion

All manner of bloviation by me cannot stem the tide of this film’s operatic largess. Napoleon is dynamite (pun intended), a grand, spectacular opus that is both thrilling and captivating not only for its attention to detail with the story but the depth of technicality provided by Gance’s direction. Whether you’re a fan of French history, a lover of silent film, or a casual observer looking for something unique and genuinely jaw-dropping to check out, Napoleon delivers legitimately awe-inspiring storytelling in a way that defies the era in which it was made, whilst simultaneously defining it. Boasting extravagance and editorial splendour, frantic camerawork and a towering performance by Albert Dieudonne in the title role, as well as a cast of thousands propping up the decade-spanning width of Abel Gance’s story, Napoleon is arguably one of the greatest films ever made, and certainly one of the most amazing silent films you’ll ever witness. Just astonishing.

i want to watch this movie!!!

By all means, go right ahead!