Movie Review – Old Dark House, The (1932)

Principal Cast : Boris Karloff, Melvyn Douglas, Raymond Massey, Gloria Stuart, Charles Laughton, Lilian Bond, Ernest Thesiger, Eva Moore, Brember Wills, Elspeth Dudgeon.

Synopsis: Seeking shelter from a storm, five travelers are in for a bizarre and terrifying night when they stumble upon the Femm family estate.

********

There’s something deeply unsettling about The Old Dark House. Maybe it’s the misty, rain-lashed hills of the Welsh countryside, the cavernous gothic architecture slathered in shadow and menace, or perhaps it’s Boris Karloff’s menacing, mostly mute butler glowering from the edges of the frame. Whatever it is, James Whale’s 1932 horror-comedy hybrid is a film brimming with sinister atmosphere, off-kilter energy and what can only be described as a delightfully theatrical sense of the macabre. It’s a strange film, one that seems caught in the midst of cinematic evolution: not quite silent, not quite talkie, certainly not subtle, but undeniably intriguing for fans of early genre cinema.

Based on the 1927 novel Benighted by J.B. Priestley, The Old Dark House takes the tried-and-true premise of strangers stranded in an isolated mansion during a storm and infuses it with Whale’s puckish sensibility and a cast to die for. The script – penned by Benn W. Levy – is more serviceable than stellar, occasionally tipping into overripe dialogue or illogical plotting, but it’s never dull, thanks largely to the ensemble cast giving it far more gravity than it probably deserves.

The plot is delightfully absurd: after being caught in a torrential downpour, a trio of travellers – the stern Philip Waverton (Raymond Massey), his glamorous wife Margaret (Gloria Stuart), and their sardonic friend Penderel (Melvyn Douglas) – stumble upon the crumbling Femm family estate. Inside, they encounter a rogue’s gallery of grotesques: the effete Horace Femm (a marvellously camp Ernest Thesiger), his religious zealot of a sister Rebecca (Eva Moore, in full Yorkshire hellfire mode), and their nearly silent, towering servant Morgan (Karloff), a drunken brute with barely repressed violent urges. Upstairs, there’s an ancient patriarch hidden in the attic – the 102-year-old Sir Roderick Femm, portrayed in an amusingly gender-swapped turn by actress Elspeth Dudgeon under heavy makeup – and a locked room concealing a greater, deadlier secret.

As if things weren’t crowded enough, the house receives more guests: boisterous industrialist Sir William Porterhouse (Charles Laughton, in his American film debut) and his chorus-girl companion Gladys (Lilian Bond), whose arrival adds an unexpectedly poignant element of class tension and romance. What follows is an eccentric, often chaotic blend of suspense, horror, comedy, and philosophical musings – with every character a potential threat, and no escape from the relentless weather outside.

Make no mistake, this is very much a film of its time. The dialogue, full of clipped Britishisms and now-antiquated turns of phrase, might leave modern audiences perplexed. Some of the performances tilt into overwrought territory, particularly Moore’s shrieking turn as Rebecca. And yes, the plot occasionally meanders, with characters doing very silly things in the service of very thin logic. But beneath all that, The Old Dark House is a showcase of Whale’s ability to balance tonal extremes – horror and comedy, parody and sincerity – in a way that remains oddly compelling.

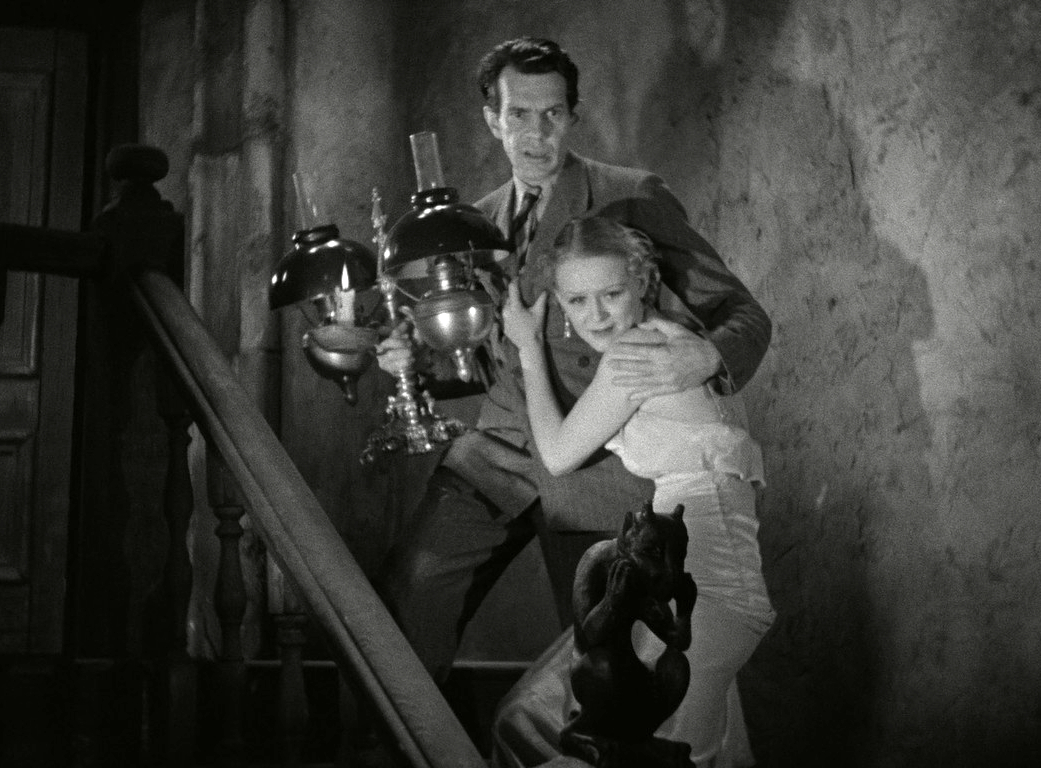

There’s a deliberate theatricality to the production, from the exaggerated personalities to the shadow-drenched cinematography by Arthur Edeson, who also shot Frankenstein and The Maltese Falcon. The house itself becomes a character, groaning and creaking with a haunted life of its own. Whale makes terrific use of the space: towering staircases, looming windows, and cavernous rooms become backdrops for dramatic silhouettes and sudden bursts of terror. The opening scene – a rockslide nearly crushing the protagonists’ car – is a particularly effective use of miniatures and visual trickery, setting the stage for the heightened realism to follow.

Karloff, fresh off Frankenstein, is again relegated to a near-wordless monster role here, all lumbering gait and wild-eyed menace. As Morgan, he is simultaneously pitiable and terrifying – a blunt instrument teetering on the edge of chaos. He’s not given much to do narratively, but his looming presence adds a necessary threat level to the film’s otherwise mostly verbal confrontations. Meanwhile, Ernest Thesiger’s Horace practically steals the show, swanning about with droll commentary and a nervous energy that feels like Noël Coward fell into a Hammer Horror production.

Where The Old Dark House really comes alive is in its moments of stillness – the quiet dread of creaking floorboards, the flicker of candlelight on a frightened face, the way Whale holds a shot just long enough to make the viewer feel uncomfortable. There’s a creeping tension that bubbles underneath the silliness, and when the film does lurch into horror territory, it does so with a weirdly satisfying punch. Admittedly, modern horror fans weaned on James Wan-style jump scares and gore may find this all a bit too quaint. But for aficionados of golden-age genre filmmaking, there’s a lot to love.

One of the more fascinating aspects of The Old Dark House is how it both honours and subverts the conventions of the haunted house narrative. Whale’s tongue is clearly planted in cheek for much of it – from the arch line deliveries to the exaggerated character types – but he never fully tips over into parody. Instead, he walks a fine line, creating a film that feels like it’s gently mocking its own genre while still delivering on the requisite chills. It’s as if Whale is saying, “Yes, this is all a bit ridiculous, but you’re going to enjoy yourself anyway.” There’s also a streak of social commentary running beneath the surface, although how much of that resonates today is debatable. The upstairs-downstairs dynamics, the contrast between stiff-upper-lip aristocracy and working-class resilience, the underlying critique of religious zealotry – it’s all there, if a bit undercooked. Laughton’s Porterhouse, in particular, feels like a character lifted from a different film entirely, but his emotional vulnerability adds a surprisingly human layer to the madness unfolding around him.

I’ll admit there were moments where I found myself slightly adrift in the film’s arch tone and seemingly random shifts in focus. The pacing can be uneven, and the structure of the narrative leans heavily on coincidence and contrivance. But even in its clunkier sequences, there’s an undeniable charm to The Old Dark House. It’s a film brimming with creative energy, playful irreverence, and genuine cinematic craft. In the end, The Old Dark House is perhaps best appreciated not as a polished classic but as an artefact of genre evolution – a stepping stone between the expressionist horrors of the silent era and the more codified chills of post-war horror cinema. It’s odd, it’s awkward, it’s occasionally brilliant, and it’s never, ever boring. For fans of Whale’s other works – particularly Frankenstein and The Invisible Man – this is an essential, if underappreciated, companion piece. Recommended with a mild shrug and a theatrical flourish.