Movie Review – Cabinet of Dr Caligari, The (1920)

Principal Cast : Werner Krause, Conrad Veidt, Friederich Fehér, Lil Dagover, Hans Heinreich von Twardowski, Rudolf Lettinger.

Synopsis: Hypnotist Dr. Caligari uses a somnambulist, Cesare, to commit murders.

********

One of the 100 Landmark Films of the 20th Century, Robert Wiene’s expressionist masterpiece remains arguably one of the most influential and significant films—silent or otherwise—ever made. While the central narrative might feel a touch anaemic by today’s standards, the cinematography, makeup, lighting and framing of this German silent classic—shot between 1919 and 1920—boast stark, unnerving examples of a twisted visual style that would all but be subsumed by filmmakers like Tim Burton in the 1990s. The Cabinet of Dr Caligari is not only tremendously atmospheric but also a seminal work of visual storytelling, a striking piece of moving art that demonstrates a command of cinematic language at a time when the medium was still in its infancy. Its distorted imagery and gothic tone still evoke a creeping unease more than a century after its debut.

Told primarily in flashback, the story revolves around Francis (Friedrich Fehér), a young man who recounts a series of tragic and mysterious events in the fictional town of Holstenwall. A sinister showman, Dr Caligari (Werner Krauss), arrives at a carnival with his exhibit, a somnambulist named Cesare (Conrad Veidt), who can allegedly predict the future. When a series of murders begins to plague the town, Francis suspects the eerie doctor is using the sleepwalking Cesare to carry out his malevolent schemes. As Francis investigates further, the tale becomes increasingly surreal, culminating in a final twist that reframes everything we’ve seen and blurs the boundaries between madness and reality.

The Cabinet of Dr Caligari is not only essential to the evolution of cinematic language but also a fertile ground for critical analysis, especially in its subtextual exploration of themes such as authoritarianism, psychological manipulation, control, and mass hysteria. Many scholars and online resources contend that the film reflects the socio-political anxieties of post-World War I Germany—suggesting the country harboured an unconscious desire to be led by a tyrant, a chillingly prescient notion given the events that would follow with the rise of fascism. It’s a compelling theory, and while I’m not entirely convinced—perhaps owing to the cultural distance a century has imposed—it’s impossible to ignore the film’s bleak aesthetic and philosophical weight, which certainly suggest a deeply cynical worldview from screenwriters Carl Mayer and Hans Janowitz. Both men, veterans of the German Revolution and witnesses to the trauma of the Great War, infused the film with a sense of foreboding and despair that mirrors their own disillusionment.

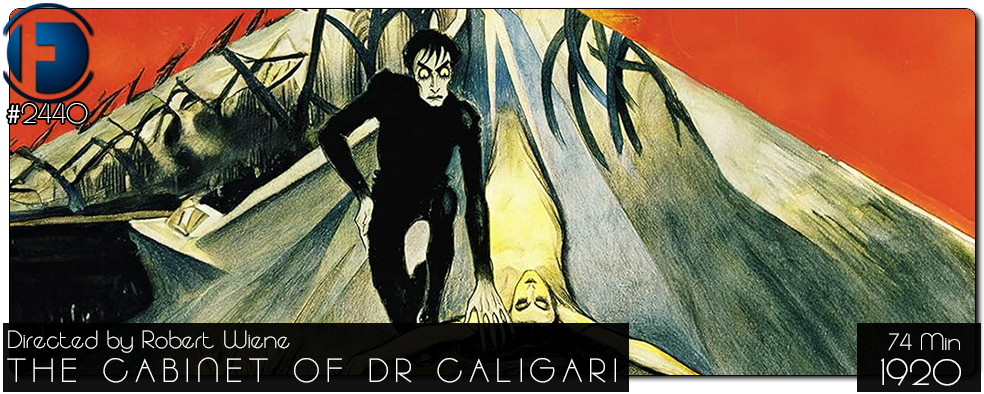

This pervasive darkness is realised through an extraordinary visual palette, driven by Wiene’s visionary direction and executed with haunting precision by cinematographer Willy Hameister. Wiene, himself a German Jew, brought an unmatched inventiveness to this early example of cinematic ‘unrealism’. The film’s angular set design, with its skewed backdrops, painted shadows and distorted architecture, established the visual shorthand of German Expressionism, where psychological states are externalised through stylised mise-en-scène. The houses, windows, rooftops and alleyways of Holstenwall resemble a nightmarish fever dream, a warped reality painted onto canvas and wood, guiding the viewer’s eye toward the human figures like silhouettes trapped in an absurdist painting.

The film is often cited as a cornerstone of the horror genre, and rightly so. Caligari himself—stooped, wide-eyed and malicious—is one of the earliest incarnations of the ‘mad doctor’ archetype, his appearance so iconic it continues to influence character design and visual storytelling even today. Wiene achieves an oppressive sense of dread through his use of off-kilter camera angles, abrupt edits and the disorienting geometry of his sets. I mentioned Tim Burton earlier, but I was also struck by how much of The Nightmare Before Christmas owes to this film’s aesthetic. The exaggerated shadows, warped lines and claustrophobic staging feel like a precursor to the gothic stop-motion style that Henry Selick and Burton would later popularise.

Central to the film’s effectiveness is the performance of Werner Krauss as Dr Caligari. Krauss is utterly mesmerising, his heavy makeup and exaggerated gestures lending the character an almost mythic quality. With his wild hair, dark-rimmed spectacles and sinister smirk, he straddles the line between deranged scientist and unholy magician. It’s a performance steeped in silent-era theatricality, where gestures speak louder than dialogue ever could, and in this context, Krauss is magnetic. Conrad Veidt, meanwhile, gives a deeply memorable performance as Cesare, the sleepwalking killer. Despite having relatively little dialogue—or, indeed, agency—Veidt commands the screen with an eerie physicality that conveys both menace and pathos. There’s something deeply tragic about Cesare, a man caught in the grip of another’s will, and Veidt captures this inner turmoil with economy and grace. His hollow-eyed stare would become one of the most enduring images of silent horror, and his work here undoubtedly paved the way for his later role in The Man Who Laughs (1928), which would in turn inspire the creation of the Joker in Batman lore.

Wiene’s decision to end the film with a twist—revealing that the story we’ve just seen may have been the delusions of a madman—elevates The Cabinet of Dr Caligari from a visually inventive murder mystery to something far more psychologically disturbing. It’s a proto-Shutter Island moment, a narrative sleight of hand that forces the audience to question the reliability of everything they’ve just witnessed. In a modern context, it might feel like a gimmick—we’ve seen the “it was all a dream” trope done to death—but in 1920, this kind of narrative subversion was groundbreaking. The twist not only recontextualises the plot but also deepens the film’s engagement with themes of mental illness, control, and the subjective nature of truth. It’s a masterstroke of storytelling, and one that lingers long after the final frame.

Had the film merely ended with the reveal of Caligari controlling Cesare, it would still have stood as a visually arresting oddity, a product of its time with an eye for the uncanny. But that final scene changes everything. It reframes the entire narrative as the hallucinations of a psychiatric patient, turning Caligari from an external antagonist into a projection of internal trauma. It’s a neat little rug-pull, and one that encourages repeat viewings to piece together the clues. It’s also why the film endures—not just for its pioneering aesthetics, but because it invites interpretation. It rewards analysis. It remains unsettling.

If you’re a student of film history or even casually interested in the evolution of cinematic language, then The Cabinet of Dr Caligari is essential viewing. It’s the kind of film that invites both admiration and interrogation, where every frame is packed with symbolic intent. Casual viewers, admittedly, may struggle with its overt theatricality, silent-era acting, and jarring visuals—it’s not a film that meets the audience halfway. But for those of us who relish being challenged by cinema, who love being immersed in an artist’s vision no matter how alien or antiquated it may seem, there’s an immense amount to savour here.

A titan of the silent era and easily one of the most visually inventive films ever made, The Cabinet of Dr Caligari stands as a conviction of the power of the cinema. Its influence can be seen in everything from Metropolis to Frankenstein, from Edward Scissorhands to Black Swan, and its themes continue to resonate in a world still grappling with madness, manipulation, and the tenuous nature of reality. Unsettling, beautiful, and boldly original, Wiene’s classic remains a cornerstone of horror and a milestone in the evolution of film as art. The Cabinet of Dr Caligari comes thoroughly recommended.