Movie Review – Freaks (1932)

Principal Cast : Wallace Ford, Leila Hyams, Olga Baclanova, Rosco Ates, Henry Victor, Harry Earles, Daisy Earles, Rose Dione, Daisy & Violet Hilton, Schlitzie, Josephine Joseph, Johnny Eck, Frances O’Connor, Peter Robinson, Ola Roderick, Koo Koo, Prince Randian, Martha Morris, Elvira Snow, Jenny Lee Snow, Elizabeth Green, Angelo Rossitto, Edward Brophy, Matt McHugh.

Synopsis: A circus’ beautiful trapeze artist agrees to marry the leader of side-show performers, but his deformed friends discover she is only marrying him for his inheritance.

********

It’s hard to watch Tod Browning’s Freaks without trying to work out if he was aiming for pure sensationalism or something more sympathetic. The controversial 1930’s film, which was heavily edited in some territories and outright banned in others, is either one of the most curious little films or the most horrible; starring a bevvy of then-popular human sideshow attractions (you know, the bearded woman, the world’s strongest man, a set of conjoined twins, among others) Freaks could be said to trade off on the misery “normal” people objectify on these hapless souls, but it could equally be so that Tod Browning was attempting to get his audience to side with those we might otherwise scorn, stripping bare our hypocrisy in doing so. Strange and terrible but filled with a sense of hope, Freaks is a film that will linger long with you after it’s concluded and make you question your own sense of self-worth.

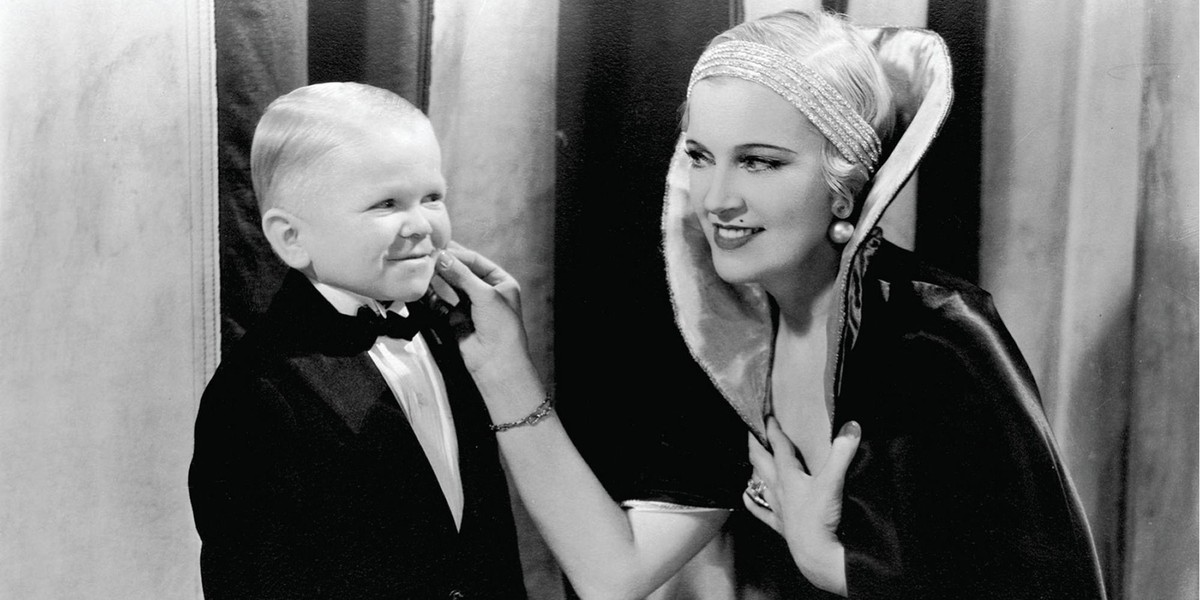

At a rural carnival sideshow populated by the grotesque and freakish of human beings, a conniving trapeze artist, Cleopatra (Olga Baclanova) and the resident strongman, Hercules (Henry Victor), conspire to murder dwarf Hans (Harry Earles) and steal his hidden fortune. Hans’ unrequited lover, Freida (Daisy Earles, Harry’s real-life sister) sees Cleo as a usurper, but Hans cannot be talked out of marrying the regular sized woman. Meanwhile, stuttering circus clown Roscoe (Roscoe Ates, playing himself) is married to one of conjoined twins, Daisy, whose sister Violet intends to marry the circus’ owner. So when Phroso (Wallace Ford), who loves the beautiful Venus (Leila Hyams), discovers the murderous plot they, together with the gaggle of bizarre human shapes around them, plan to stop Hans from meeting foul play.

Tod Browning aims for the sensationally voyeuristic with Freaks, a film categorised as a drama but one which could equally stand alongside the best of the early horror genre. Browning set his film in a circus and showcased not just actors made up to look positively unreal, but actual, living humans with all manner of physical deformities. People with dwarfism (the Earles siblings), microcephaly, sacral agenesis, a set of British conjoined twins, and a variety of the deformed and malformed sideshow acts of the early 20th century play roles in this incredibly bizarre film, one which feels like its supposed to be some kind of learning experience about acceptance and humanity but often gets lost in the gratuity of it all. This isn’t to suggest Browning’s film isn’t good, because it is quite charming (as well as utterly grotesque), but only in that can’t-look-away trainwreck kind of charming.

As a story I guess the film works well enough – a beautiful trapeze artist wants to swindle a midget out of a fortune by marrying, and then poisoning him. It’s not exactly rocket science, which leads me to think that Browning’s motives may have been more sensationalised than the soft-focused romantic subplots might suggest. The “freaks” of the film are all depicted as being relatively confident with their lot in life, given the film was shot during the Great Depression there was a notion that the screenplay, by Willis Goldbeck and Leon Gordon, is representative of dichotomy of American wealthy elites and the jobless poor, and I guess if you squint you could make a case for that. Today, however, nearly a century beyond that defining moment in global history, the film plays like a straight-up drama and although the performances from most are especially wooden and clunky, it still works. The appearances of the gathering of disabled and deformed characters tends to play hard into our sympathy for the sheer sake of voyeuristic scandal but Browning never pushes the limits of alienating us towards them; these people are just that, people who have some kind of unfortunate physical disfigurement that many might consider weird, but with a fairly pastoral tone the film depicts them as relatively normal.

I can’t help but be struck somewhat by a similarity of tone to Lynch’s The Elephant Man, in which the incredibly tragic story of John Merrick tore at the heart of what it means to be human. Freaks goes a fair way to depicting its stable of stars in compellingly normal scenarios; from getting dressed, partying, having babies, dining together, to sitting around chatting with each other, which humanises them in a way some audiences may find uncomfortable. The jarring impact of seeing these often distressingly disabled people in mundane social settings contrasts heavily with the bookending “sideshow freak” sequences through which they make their money; again, Browning seems to be able to balance the ghastly with the empathetic, jettisoning simple shock value for a more humane, understanding focus. What’s more tragic is knowing that a large portion of the “freaks” in the film actually made their real-life living being freaks for people to gawk at, on stage or in other shows. Several led quite tragic lives off-screen (the conjoined twins, for example, were treated appallingly by their various owners – yes, they were owned – until being abandoned at a supermarket and forced into relative obscurity through sheer dumb luck) and others had quite good careers (Harry and Daisy Earles were part of a small-statured family that traded heavily on their diminutive size, with Harry appearing several years later as a Munchkin in The Wizard of Oz), but seeing them all gathered here with their various disabilities having a good time is strangely beautiful. In short, Freaks demands that we see these people as people first, freaks last.

As he did with Dracula the previous year, Tod Browning does superbly well with the film’s more horrific moments. The way he uses the camera to build the story around some quite average performances is masterful, maximising his better actors whilst reducing the disadvantage of the poorer ones. He also evokes some significant atmosphere of dread around the setting, as if the surrounding woodland is closing in, pressing the bunch tighter together as Cleo’s poisoning plot starts to unfold. His use of shadows and clever lighting to enhance the “freakish” nature of the film’s stars, particularly on outdoor sequences (which were obviously shot indoors, but hey) is remarkable, and the film’s terrifying climax, in which Cleo is hounded through the encampment by almost all the misshapen creatures within is pure genre genius. The ratcheting terror, as the grotesque and obscene approach the murderess through the mud and rain of that stormy final night, is a sequence film fans will savour for its inventiveness and sublime horror aesthetic.

Sadly, we will never get to see Tod Browning’s full vision for Freaks. The original theatrical release clocked in at around 90 minutes, but after some reportedly awful test screenings the studio made significant cuts, and additional alternative footage was used to make the film more palatable. The film’s famous final shots, in which Cleopatra is seen in her own “Freakish” state after being attacked by the carnival folk, seems confusing to many because the previous scene, in which the fate of both Cleo and her conspirator Hercules as they’re attacked are shown in all its glory, was among those moments forever lost to us, resulting in a quite jarring (but still effective) denouement for the vanquished villainess, whilst a tacky romantic coda for Hans and Freida grinds with the sting of studio interference. The version we’re left with runs a brisk 60 minutes and change, perhaps adding to the mystique of this incredibly intriguing cinematic venture.

Freaks isn’t a film for the casually curious. It’s a fairly confronting work balancing exploitation with legitimising those perceived as “different” through no fault of their own. Browning’s visual style is beautiful, even if the story and several performances lack the prestige of, say, Dracula, and as an argument for telling truly human stories it’s hard to go past. But it’s not always clear what the film’s motivations are, and it’s in this regard that Freaks comes with a caveat. My belief is that Browning was attempting to unmask the sideshow exhibits and medical curiosities as actual human beings, not the monsters the entertainment industry pigeonholed them as. Even occasionally the film does slip into a more salacious tone, using the various physical abnormalities to generate sadness or a sense of tragic helplessness in the viewer, yet on the whole I think Browning’s motivations were more pure than the title and overall outcome musters in our subconscious.