Movie Review – Blonde

Principal Cast : Ana de Armas, Adrien Brody, Bobby Cannavale, Xavier Samuel, Julianne Nicholson, Evan Williams, Toby Huss, Lily Fisher, David Warshofsky, Caspar Phillipson, Dan Butler, Sara Paxton, Rebecca Wisocky, Tygh Runyan, Michael Drayer, Patrick Brennan, Eric Matheny, Lucy DeVito, Scott McNairy, Ravil Isyanov, Catherine Dent, Michael Masini, Ned Bellamy.

Synopsis: A fictionalized chronicle of the inner life of Marilyn Monroe.

********

Never has the gap between my enjoyment of a film and the performance of said film’s leading lady been so, oh so wide. Blonde is a repugnant, arrogant monolith of hubris and misogyny, led by an actress in what should, by rights, become her career-defining role and snag innumerable awards. Hugely controversial material and motives surround Blonde’s production, a heavily fictionalised retelling of the life of 60’s sex-symbol Marilyn Monroe, from her childhood through to eventual death of drug overdose at the incredibly sad age of 36; the film elicits a variety of angering responses as it stridently and obviously asks a singular question of both the filmmaker and the viewer. As Marilyn herself questions at one point in the movie – “am I a piece of meat?” To wit: Blonde is both a diatribe against the exploitation of Norma Jeane and an exhibitor of exploitation of Norma Jeane, a dichotomy not lost on me amid this near three-hour examination of one woman’s mental breakdown to the point of suicide.

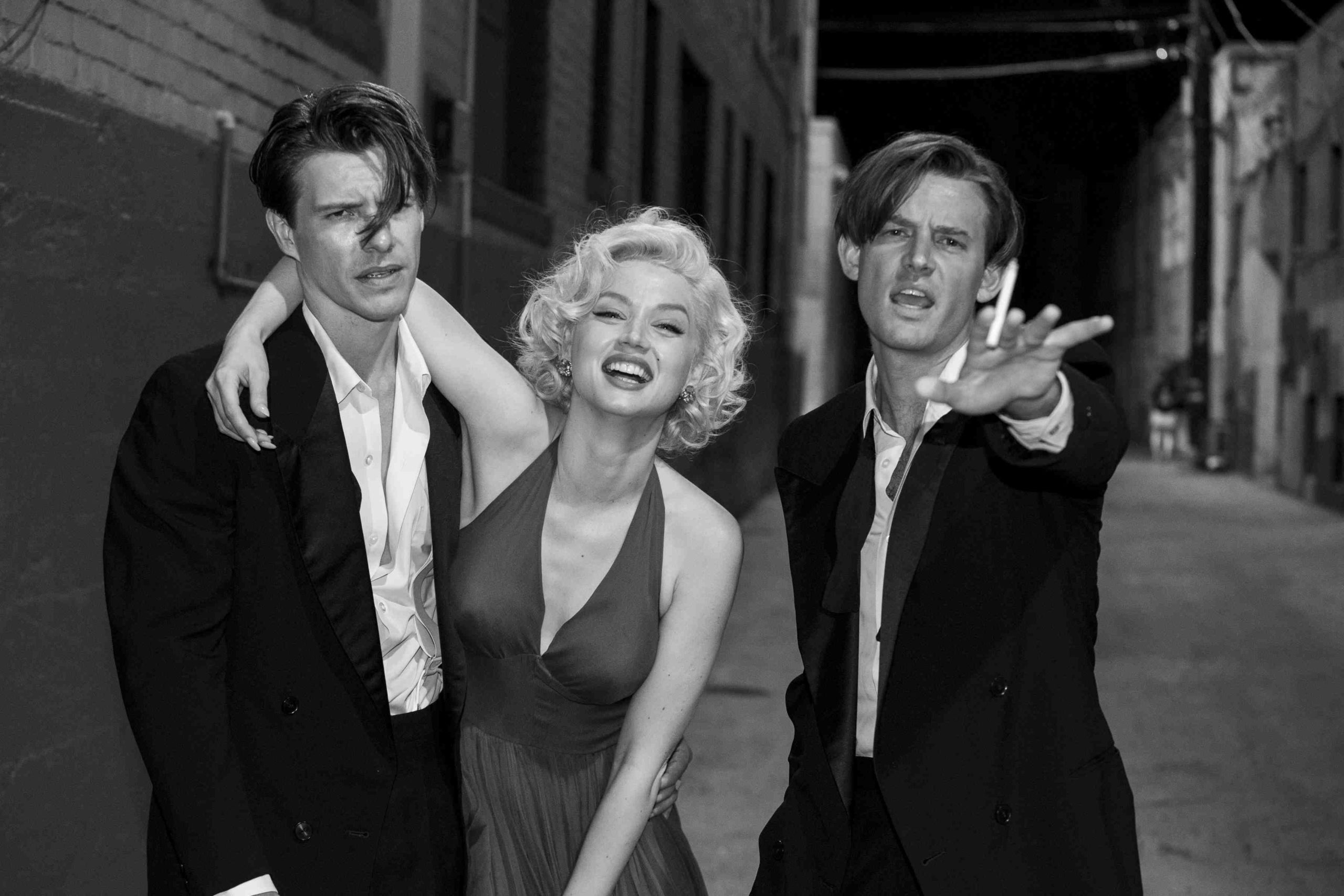

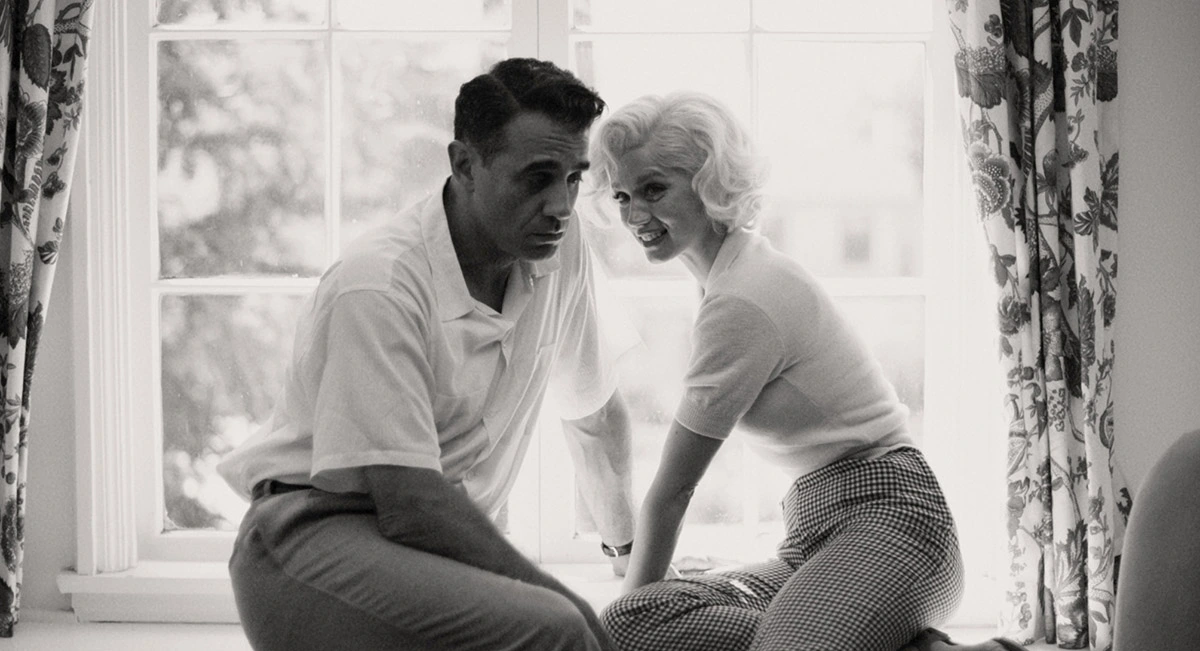

In the early 1950’s, aspiring actress and former nude model Norma Jeane Mortenson (Ana de Armas) finds herself cast in a Hollywood B-movie after being sexually assaulted and raped by a producer. This is simply another in a long line of degrading encounters for the woman, whom as a young girl was raised by her mentally unstable mother, Gladys (Julianne Nicholson), and who believes her long lost father will eventually return to love her at some point. Norma Jeane, working under the stage name Marilyn Monroe, struggles with working in the male-dominated movie industry and suffers continued bouts of anxiety and depression, alleviated somewhat by various relationships with, alternately, the son of Charlie Chaplin, Cass (Xavier Samuel) and his friend Eddy Robinson Jr (Evan Williams), a retired baseball athlete (Bobby Cannavale), and even renowned playwright Arthur Miller (Adrien Brody), most of which end in violence or dissatisfaction. As her career rises, Norma Jeane becomes entangled with the US President, Kennedy (Caspar Phillipson) and it is through this relationship that her life, her desire to be a mother, finds her on the precipice of tragedy.

Blonde is a challenging film. Personally, I found it dreadfully confronting, not so much for the subject matter but for the lurid, distasteful manner in which Marilyn Monroe, a figure of much adoration and retrospective sorrow, is treated throughout. As an object of sexual desire throughout both her life and the decades since, Monroe’s life is perhaps undeserving of such fanciful and propagandist treatment. Based on Joyce Carol Oates’ 2000 novel, Blonde’s fictional retelling of Monroe’s life is nothing short of sensationalist pornography, a fornication with fabrication far removed from even a “based on a true story” apologist card. Director Andrew Dominik, who also writes the screenplay, seems to have found himself making some kind of statement on the sexualisation and degradation suffered by Monroe (and, to some extent, woman in general) and how Hollywood treated her as a literal piece of meat, whilst simultaneously treating her story as exactly that – a piece of meat to be gorged upon by insatiable men – and the film’s tone is one of disgraceful incomplexity. We’re at a point in society, I like to hope, where usurping a woman’s legacy – a complex, controversial legacy in almost every respect – in such a dark, malignant manner of falsehood is something to be ashamed of.

I watched the film through gritted teeth as Dominik’s stylised recreation of Hollywood’s 50’s and 60’s came with a stark monochrome palette and shifting aspect ratios, a director enamoured with the art of it all and yet unwilling to offer restraint when dizzying rage lurks behind the screen. Indeed, the film’s aesthetic is one of legitimate art-house griefscape, a tragedy for both Monroe, actress Ana de Armas, and us as viewers, forced to quite literally witness a woman being so humiliated, so degraded, so maltreated by those around her who only wanted one thing: her body. It’s uncomfortable to watch but not in a good, expand-your-viewpoint kind of way. This is an incredibly triggering film, filled with sexualised violence and themes of rape, abortion, mental illness and self-worth, the latter of which was in limited supply for poor Norma Jeane, so if you’re wary of approaching material of such explosive or emotional weight it might be best to skip this one.

As awful as Blonde is to watch, the performance of Ana de Armas in the title role is nothing short of astonishing. Asked to deliver a searing fictional portrayal of one of the 20th century’s most famous women, de Armas delivers a pitch-perfect, doe-eyed and heart-breaking turn, a wrenching, honestly affected and remarkably sour-yet-strong depiction of Monroe from screen ingenue to broken, wretched dance-monkey. The complex nature of Norma Jeane’s dichotomous relationship with the public as Marilyn Monroe isn’t examined in anywhere near enough detail, as much as she’s forced to endure a litany of unhappy relationships, abortions and miscarriages (honestly, if I’d lived her life as depicted by Dominik’s rancid creative choices, I’d have offed myself too), de Armas’ performance is one of grace, maturity and incredible depth. Again, the film itself is a train wreck of hideousness, but Ana de Armas is a beacon of performative brilliance inside it.

Supporting turns from the likes of Bobby Cannavale, as former baseballer Joe DiMaggio, and Adrian Brody, as Arthur Miller, offer historical context to Norma Jeane’s life off-screen – in keeping with Oates’ novel, the real-life people aren’t named outright or credited as anything other than their career titles (athlete, author, President etc), but it’s pretty obvious who these people are – whilst the appearance of Aussie actor Xavier Samuel, as the resentful and dilettante son of silent screen star Charlie Chaplin, and Evan Williams as the son of Warner Bros star Edward G Robinson, who engage in a polyamorous relationship with the screen siren is among the film’s least resistant hurdles of enjoyment. The film’s torturous opening sequence, in which a young Norma Jeane – played with remarkable effectiveness by young Lily Fisher – endures her embittered and utterly insane mother’s “parenting”, including driving through a massive wildfire and nearly being drowned in the bathtub, and I nearly switched it off at this point. It’s as if the film enjoys Norma Jeane’s suffering, a perculiar delight in ignominy and indignity captured by Dominik’s inescapably glaring spotlight-lit camerawork.

My distaste for the film isn’t without its caveats. There was one moment that did stand out as a brilliant piece of creative muscle-flexing. At one point Marilyn arrives at a film premiere, to the clamour of an adoring waiting crowd. As the flashbulbs pop and the hubbub intensifies, Marilyn sashays through the baying crowd, a crowd of entirely men whose mouths distort and distend, as if in yearning to taste her very flesh in what amounts to a nightmarish visual cue akin to the nature of the subject’s mindset. For this moment alone I give Andrew Dominik credit; his film is a weird mix of Kubrick’s distant, ice-cold visual tone and Zack Snyder’s hyper-stylised kinetics, with a lot of green-screen, digital artifice and Lurhmann-esque flamboyance in key sequences. Despite this, Blonde’s inelegant tone and desire to torture us with this inexplicably lurid tragedy-fable in such a grotesque manner is baffling. The hammer blows come thick and fast, an inescapable whirlpool of assaultive behaviour and misogyny, no doubt rooted in realism but delivered without a shred of nuance. In Blonde, men are creatures of base desires, not complicated entities in their own right, animalistic deviants driven by lust and power, which isn’t so much the issue as is the continued tsunami of awfulness Norma Jeane’s story underwent within this context. It’s an unsubtle and unsavoury take on both Monroe’s career and the period of Hollywood in which she lived, and I’ve no doubt a lot of what transpires in the film may be rooted in conspiratorial anecdotes, but if sullying the name of a real person utilising fictionalised encounters and unsubstantiated events then it leaves a very, very sour taste in one’s mouth.

The predominant feeling I had whilst watching Blonde was revulsion – not for the de Armas or Norma Jeane, but for the way in which her body, her soul, her mind, were violated in such a tawdry manner throughout the movie. This is mental torture-porn at its very worst, and while an incredibly difficult watch should be endured if only for Ana de Armas’ defining performance. I want to say I think we’ll see Blonde feature prominently in the various industry award’s nights but I sincerely wish we didn’t: de Armas deserves every award under the sun for making this jarring film even the slightest bit palatable (which isn’t saying a lot), and as Marilyn/Norma Jeane she’s astounding. Blonde, however, is ghastly; a fever dream nightmare subjecting us to a horrifying, despairing descent into tragedy that offers nothing by way of intellectual or emotional catharsis at what we see. Just a dour, terminally dreadful three hours.