Movie Review – Amistad

Principal Cast : Djimon Hounsou, Matthew McConaughey, Anthony Hopkins, Morgan Freeman, Nigel Hawthorne, David Paymer, Pete Postlethwaite, Stellan Skarsgard, Razaaq Adoti, Abu Bakaar Fofanah, Anna Paquin, Tomas Milian, Chiwetel Ejiofor, Derrick Ashong, Gino Silva, John Ortiz, Kevin J O’Connor, Ralph Brown, Darren E Burrows, Xander Berkeley, Allan Rich, Paul Guilfoyle, Peter Firth, Jeremy Northam, Arliss Howard, Austin Pendleton, Pedro Armendariz.

Synopsis: In 1839, the revolt of African Mende captives aboard a Spanish owned ship causes a major controversy in the United States when the ship is captured off the coast of Long Island. The courts must decide whether the Mende are slaves or legally free.

********

A stacked all-star cast (of mostly men) deliver a sombre, occasionally shocking, unforgettable story of what it means to be free in Spielberg’s Amistad, based on the real-life story of a group of West African captives who find themselves in the American court system after their “ownership” is disputed by various parties. Amistad serves as the breakout performance of Djimon Hounsou, in the lead role of Cinque, the unofficial leader of the group of captives who led an insurrection aboard the Spanish ship La Amistad, after which the film is named, in 1839. Hounsou, incredibly overlooked for an Oscar-nomination for his turn here, is ably abetted by the likes of Morgan Freeman, Anthony Hopkins and Matthew McConaughey as well as several solid supporting players and a number of notable cameos – including a former US Supreme Court Judge – and essays a genuinely moving story that, if you believe Spielberg, led somewhat consequently to the American Civil War and the eventual outlawing of slavery.

The historical case depicted in Amistad is an intriguing one, and a particularly profound one for the United States and the issue of civil rights. In the late 1830’s, a Spanish schooner, La Amistad, is heading for Cuba with a cargo containing a large group of captured West African people from the Mende tribe, among others. An insurrection, led by Cinque (Hounsou) leaves all but two of the Spanish crew dead – navigators Ruiz (Geno Silva) and Montez (John Ortiz) thwart their attempts to return to Africa and they are, instead, picked up by the US Navy. The Mende are imprisoned under charges of murder. Their defence, led by property lawyer Roger Berman (Matthew McConaughey), and his patrons Lewis Tappan (Stellan Skarsgard) and a black associate, Theodore Joadson (Morgan Freeman) is predicated upon the idea that the Mende are not slaves as they were born on African soil – a claim disputed by Spain, ruled by young Queen Isabella (Anna Paquin), as well as both Ruiz and Montez, and a pair of Navy personnel claiming salvage rights to the group. After the Mende have an initial victory in a New England court, US President Martin van Buren (Nigel Hawthorne) seeks to appeal the decision as the prospect of freed “slaves” might invoke a Civil War in the nascent United States, with the Southern States (personified by Senator John Calhoun, played by Arliss Howard) priding themselves on their slave population. The matter is taken all the way to the Supreme Court, where a former President, John Quincy Adams (Anthony Hopkins), puts forth a defence invoking the US Declaration of Independence, as an argument to freeing the Mende people immediately.

Amistad is nothing of not reverent to its subject matter. Spielberg, looking for his first feature release under the newly minted DreamWorks Pictures shingle he kicked off with Geffen and Katzenberg, turned his Schindler’s List aesthetic to a more American story of prejudice and injustice to give us a story of slavery and politicking that can almost only be described as reverent. The true-life story of La Amistad is one I would have doubted many Americans had ever heard of – much less any international viewers – so for the master director to bring his focus to this small slice of the American civil rights movement, nascent as it was at the time of the events depicted in this movie, was profound indeed. However, despite its prestige and astoundingly spot-the-character-actor cast of thousands adorning this most obvious of Oscar-bait projects, Spielberg trips up over his own feet in defining the case that shaped slavery in the young nation with overly dramatic representation and histrionic White Saviour tropes that undercut a lot of what transpires. That’s not to say Amistad isn’t good – hell, it’s outright great in many respects – but it’s one of those rare Spielberg films where you can see the gears and wheels turning behind the camera to make it all happen.

Based on the cumbersomely titled non-fiction book “Mutiny On The Amistad: The Saga of Slave Revolt And Its Impact on American Abolition, Law and Diplomacy” by historian Howard Jones, from a screenplay written by Gladiator scribe David Franzoni, Spielberg tries to bring brutality and realism to what is essentially a period courtroom drama that the film never quite manages to acquit itself of with solidity. Depicting slavery in the American experience is something you do with underlying truth – the performances of the largely black cast are searing in their honesty – and there is a scene, quite distressing, in which the solders aboard the La Amistad throw off several dozen of their captives, weighted to drown at the bottom of the ocean; it’s this moment in an otherwise prosaic film where Spielberg almost jumps the shark into shock value, unbalancing the audience with screams and human ugliness out of tone with the remainder of the film. The filmmaker had, until that point, managed to make us angry enough at what white and Spanish slave traders had done until that point the movie was doing its job superbly, but at this point Spielberg pushed a little too hard and crossed several lines. Reality and realism is one thing, but knowing where to pull back a bit… that’s the key. Still, as confronting as this is, it’s a moment magnified by innumerable smaller moments of abject horror and terror threaded throughout the narrative. Franzoni’s screenplay is steeped in societal and political whims of the day – the day being the year 1839, on the Eastern seaboard of America – and you get the sense balancing the requirements of the film’s intended audience and historical accuracy were really ill-fitting bedfellows.

Spielberg wants to depict the horrors of the La Amistad’s journey from West Africa to the American coast with similar ferocity that he would afford the D-Day landings in Saving Private Ryan (a film that would come along the following year) but he’s much more restrained, circumspect in his blood, gore and human anguish save for the aforementioned sequence in which chained up captives are hurled from the decks to drown far below. Make no mistake, Amistad is a film filled with terrible imagery, but it’s homogenised somewhat for the sake of viewer comfort when, by rights, it probably shouldn’t have been. The film’s focus quickly turns to the trio of court cases in which the captive Amistad slaves are tried on US soil – the first under Judge Judson (Allan Rich), who is replaced by a supposedly easily-influenced Judge Coglin (a young Jeremy Northam), before the grand finale in the US Supreme Court – and it’s here that a lot of the two-and-fro of America’s ugly history of slavery is given full-throated condemnation by Matthew McConaughey’s Roger Baldwin, as well as Anthony Hopkin’s more circumspect President John Quincy Adams. It’s these moments of self-reflective national disgrace that Amistad comes into its own, with Franzoni giving equanimity to the argument against slavery, and populating the Southern States “States rights” claims (that are, sadly, still prevalent today) with a peppering of red-faced faux-apoplexy masquerading as indignant lawmakers trying to argue the indefensible. Modern context notwithstanding, Amistad’s stance on slavery is crystal clear and makes no bones about it.

Arguably the standout performance in the film is Djimon Hounsou, as Cinque, the strong-willed, proud African beset with desperately trying to find his freedom from captivity and return to his home. There’s a magnetic force to Hounsou’s portrayal here, an honest-to-God lightning strike of a role and actor so in tune with each other its as if he was born to play the part. Hounsou’s raw screen power boils the screen, an incendiary internal strength to the man who at his heart is good, but will fight like a lion to earn his freedom – a motif carried succinctly throughout the narrative and represented by a single fang claimed by Cinque as a reminder of his homeland. Razaaq Adoti plays Cinque’s compatriot, Yamba, who finds religion through the effort of local missionaries, with equal internalised strength despite having a smaller role, and the varied other black performers playing La Amistad captives all have small beats of character work to depict throughout the film.

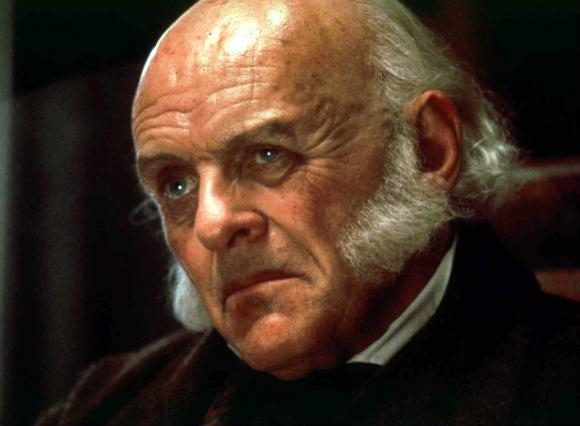

Alternatively, the role of up-and-coming lawyer Roger Baldwin was given to Matthew McConaughey, whose earnestness and straightforwardness in the previous years’ A Time To Kill, Contact (also in 1997) and U571 (2000) would turn him into an A-list celebrity, and while I think he’s an actor ill-suited to the film’s genteel tone here, he gamely goes for broke alongside his superior cast. Morgan Freeman and Stellan Skarsgard have meaty, of underused, roles as friends of Baldwins, whilst Anthony Hopkins’ limelight-stealing John Quincy Adams is an evocation of eminent power used so delightfully I’m not surprised he was afforded an Oscar nomination. A caveat: that Hopkins got an Oscar gong and Hounsou did not is one of history’s great acting oversights. Smaller roles to Pete Postlethwaite, as a prosecutor, David Paymer as US Secretary of State, Chiwetel Ejiofor as a man who translates Cinque’s native tongue into English, and Anna Paquin as the Spanish Queen are well regarded and quite easily sustain the wrangling and permutations of the various legalese spoken and delivered throughout, whilst a dithering Nigel Hawthorn, as then-US President Martin van Buren, is terrific.

Amistad’s prestige casting and story isn’t the only thing the film has working in its favour, however. Spielberg’s filmmaking style is in full flight here, manifesting as sublime framing, superb editing and Kaminski’s softly-softly cinematography make for an enchanting looking film despite some uneven pacing and propagandist leanings. John Williams’ scores the film with rich African themes and a traditionalist orchestral accompaniment in one of his more sombre, nuanced works; I think the score to Amistad would work well as a triple-play alongside Empire of The Sun and Schindler’s List, such is its ephemeral temperament. At a tick over two and a half hours there’s a question of pacing, and I admit at times that Amistad does drag its feet getting to the point a bit, but I understand Spielberg and Franzoni want to stretch out the tension as much as they can, and they do. Unfortunately, the film’s climax is something of an afterthought, a footnote of exposition lacking any catharsis or euphoria, simply having former US Supreme Court Justice Harry Blackmun read the actual verdict of the real case might have seemed impactful in the printed screenplay but I found it lacking. American viewers more familiar with rousing judicial verdicts may disagree with me.

Look, there’s a fair bit in Amistad that’s really, really great. The film wears its heart and soul on its sleeve, as Djimon Hounsou does with every tear and hard-stare of his performance in the central, pivotal role of Cinque. That a lot of folks have forgotten just how terrific an actor he can be is a tragedy in itself, as the dude is routinely cast in derivative action or thriller films in largely supporting roles. Despite the overbearing nature of Franzoni’s screenplay and McConaughey’s diffident yet earnest performance, salvaged mainly by Freeman, Hopkins and to a lesser degree Skarsgard, Amistad is a worthwhile if slightly too self-assured Oscar-bait flick that tells a riveting moment in US history that is vastly intriguing and probably deserves a wider documentary to explore the various corners of this case. Led by a command performance from Djimon Hounsou, who flourishes under Spielberg’s exacting gaze, Amistad’s legal-heavy proceedings are prodigiously enthusiastic if not always precisely rousing. I just wish I’d enjoyed it a little more.