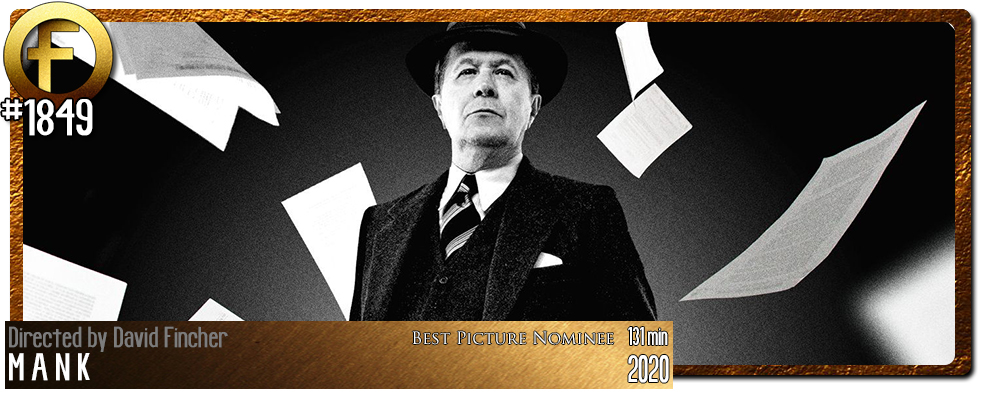

Movie Review – Mank

Principal Cast : Gary Oldman, Amanda Seyfried, Lily Collins, Arliss Howard, Tom Pelphrey, Sam Toughton, Ferdinand Kingsley, Tuppence Middleton, Tom Burke, Joseph Cross, Jamie McShane, Toby Leonard Moore, Charles Dance, Bill Nye, Jeff Harms.

Synopsis: Mank follows screenwriter Herman J. Mankiewicz’s tumultuous development of Orson Welles’ iconic masterpiece Citizen Kane (1941).

********

Fabulous. That’s the only way to describe David Fincher’s movie about a movie; to wit, the controversial development of Orson Welles’ pointed dramatic satire Citizen Kane makes for terrific fodder, led by a magnificent Gary Oldman and a luminous Amanda Seyfried. From its dusty monochrome photography to its dazzling production design and sublime costuming, not to mention Fincher’s trademark sense of showmanship, Mank might be a fatuously fabricated affair derived from actual events but hell if it isn’t an entertaining watch.

Hollywood screenwriter Herman J Mankiewicz, or “Mank” as his associates called him, was a legend of his own lifetime: an industry “fixer”, Mank was often tapped by movie studios to rewrite scripts they were developing or shooting to make them more commercial and successful. He was in is mid-forties by the time he was tapped by wunderkind radio and theatre star Orson Welles (Tom Burke) to write his magnum opus, a script that would cause controversy for its skewering of American newspaper titan William Randolph Hurst (Charles Dance) and his mistress, aspiring actress Marion Davies (Amanda Seyfried). An alcoholic, Mank spends his time holed up in an isolated cabin to work on the screenplay, attended by housekeeper Frieda (Monika Gossmann) and newly hired secretary Rita Alexander (Lily Collins), while flashback sequences introduce us to Hollywood power players such as MGM boss Louis B Mayer (Arliss Howard), Irving Thalburg (Ferdinand Kingsley) and Mank’s project babysitter, producer John Houseman (Sam Troughton). Mank’s brother Joseph (Tom Pelphrey), himself a noted Hollywood creative, also provides emotional contrast for the contrarian drunkard as he pens his most famous work.

If there’s something Hollywood loves more than a great film, it’s a great film about Hollywood. Mank is worthy of the appellation, grafting nostalgic bygone-era looks with a fascinating portrayal of an legitimate industry titan, granted life by the ever-chameleonic Gary Oldman. Howard Mankiewicz is portrayed as a man in love with words, a man in love with drink, and a man for whom a sharp tongue and battle with gambling addiction were often the cause of great misery. His undeniable talent, however, can be seen whenever we watch any of the great films he worked on (including The Wizard Of Oz); Mank doesn’t dwell to deeply on the end result of the script for Citizen Kane (the working title of which is depicted as “American” here) but rather the interpersonal conflicts surrounding Mankiewicz’ rather bohemian life.

The script for Mank comes by way of Fincher’s late father, Jack, who passed away in 2003 – the director has initially planned to make the film after completing The Game in 1997, although circumstances of the day dictated otherwise – and it’s a verbose, heady affair filled with intrigue and simmering subtexts, a delightful concoction of Hollywood politicking and the veneer of perfection surrounding the idylls of external beauty. There’s a sadness sitting uncomfortably close to the surface of Mank’s rather genteel, if somewhat seedy outer layer, a despair of the superficiality of artifice through which all our players must imbibe. Jack Fincher’s script touches on key elements of the day, working Mankiewicz’ slowly decaying sense of propriety into a hazy, smoke-filled elegy of drink and bittersweet lament. Oh sure, there’s glitzy razzmatazz here and there, but Mank is at its heart a tragic story, much like Citizen Kane, in that it showcases a towering figure at the height of his powers who has that power stripped away – Mankiewicz famously signed a contract that he would not be credited for his work on Citizen Kane, only to later recant and request to have his name on the film, causing a rift between he and Welles that would last the rest of his life – and an utter failure to acknowledge the emotional toll he takes on those around him.

It’s fair to suggest that viewers unfamiliar with either Citizen Kane or the early decades of Hollywood’s film industry might find the film a bit of a slog, or at least sit there baffled by what it’s supposed to be about. Mank isn’t interested in subtitled clues to who’s who – you’re meant to work that out for yourself – and Fincher’s direction, as flamboyant as he gets, is curiously impenetrable for those without even a cursory knowledge of this time period. Which goes a long way to determining your overall enjoyment, I’d wager. Mank will become a classic of the film-about-a-film subgenre, make no mistake, and its hugely artistic aesthetic will no doubt have it lining up for all manner of production awards (as well as the creative, for sure), but I have to wonder who Fincher made this film for? If it’s for the cineaste crowd, Mank delights but will remain more a lark than legitimate heavy-hitter. For the casual viewer, the insight insinuated by Jack Fincher’s screenplay is muddied by the incredible artistic licence his son delivers. It’s highly stylised, this film, abstaining realistic accuracy for a fancifully art-deco tone that magnifies the nostalgic elements film fans will adore but one that will make it impossibly incomprehensible for newbies. Am I gatekeeping Mank’s experiential potential? Perhaps, but it warrants stating that your enjoyment of Mank will depend largely on your foreknowledge of the events and people it loosely portrays, and at least a tangential understanding of the truth behind what transpires on screen.

In terms of performances, Gary Oldman shoulders the film through its “present day” and flashback sequences with the charisma and accentuated perspicuity we’ve come to love. Amanda Seyfried is luminous as Marion Davies but in my opinion it’s Lily Collins who maximises her screen time with a wonderful turn as Mankiewicz’ secretary, as she transcribes the writer’s words onto the page. Charles Dance makes a terrific Hurst, and Arliss Howard absolutely steals every scene he’s in as Louis B Mayer, the powerful boss of MGM Studios. Shout out too to Jamie McShane as Mankiewicz’ friend Shelly Metcalf, for his softly spoken work in a quite moving role. If you blink too quickly, you’ll also miss a very brief cameo by Bill Nye (yes, the science guy), as a politician running for the seat of California’s Governor.

If nothing else, Mank joins the likes of The Artist (a film which shares a lot of genetic DNA with this), Hail Caesar!, Chaplin and more recently Tarantino’s Once Upon A Time In Hollywood as a consummately constructed love-letter to the industry’s Golden Age. The crisp black and white cinematography, by Mindhunter lenser Erik Messerschmidt, should snap up the Oscar for that category this year, whilst Fincher’s regular composers Trent Renzor and Atticus Ross provide yet another solidly bucolic score. The little visual tweaks Fincher gives his film are also a blast; from the recurring “cigarette burn” marks artificially installed into the film periodically to suggest an old-school movie, to the mono sound mix and the use of 40’s period titles to open proceedings, it’s this attention to detail that makes Mank more than just a masturbatory circle-jerk, but a genuinely embracing cinematic experience. It helps that the film’s production design is flawless, as are the costumes, and the gamut of visual effects you might expect are absolutely seamless. In short, the production of Mank is quite possibly perfect.

Mank’s dense, literary dialogue and heady, summery tones make for compelling drama, even if the plot’s overt machinations will find ill-footing for the cinematically disinclined. Personally, I loved it, and there are a load of people who will as well; Mank is a delightful, delirious production of superb replication and starkly enjoyable performances, Oldman and Lily Collins in particular. Your mileage may vary but I thought it was fabulous.