Movie Review – Ad Astra

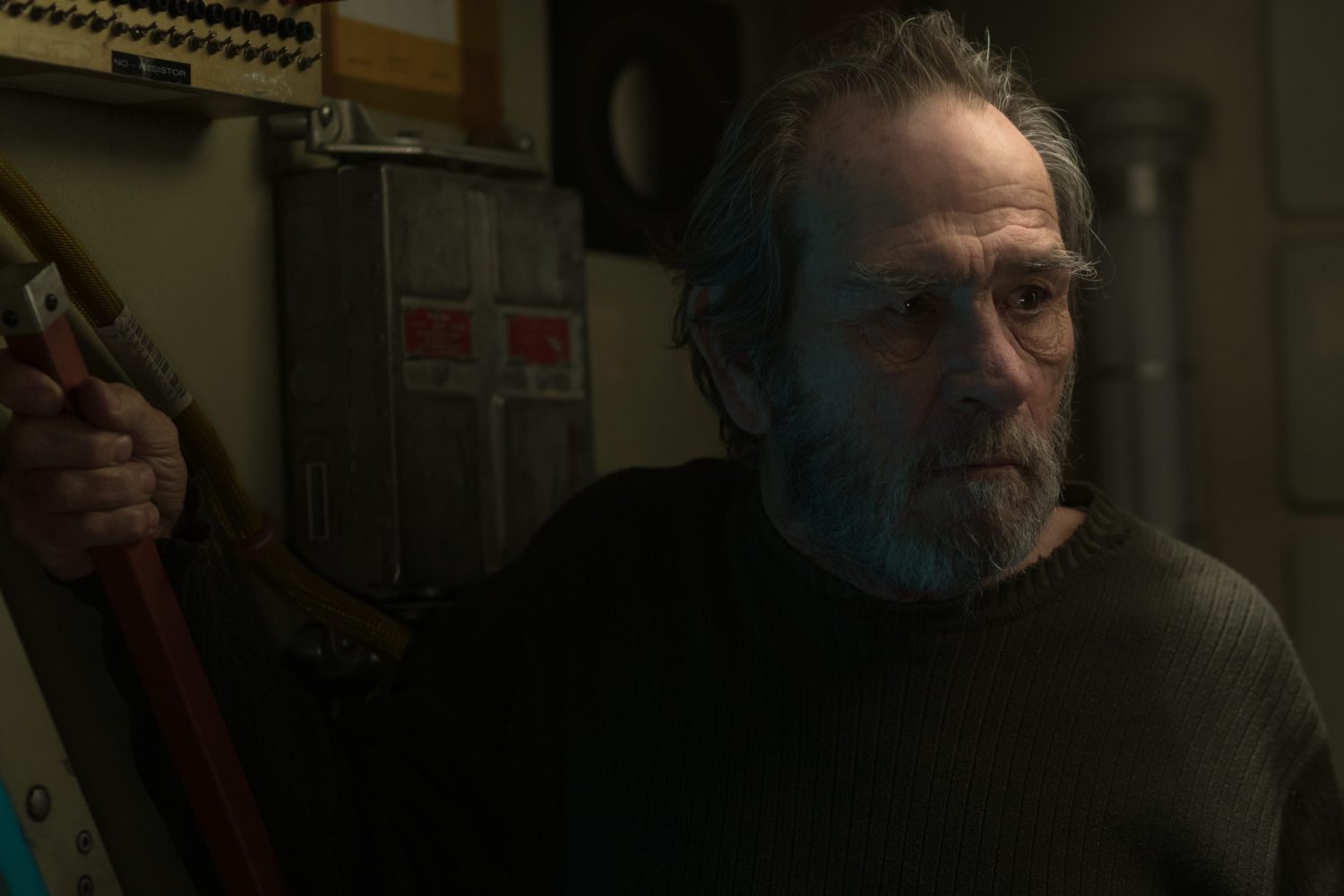

Principal Cast : Brad Pitt, Tommy Lee Jones, Ruth Negga, Liv Tyler, Donald Sutherland, John Ortiz, Greg Bryk, Loren Dean, Natasha Lyonne, John Finn, Kimberly Elise, Sean Blakemore.

Synopsis: Astronaut Roy McBride undertakes a mission across an unforgiving solar system to uncover the truth about his missing father and his doomed expedition that now, 30 years later, threatens the universe.

********

James Gray’s Ad Astra surprised me by being pretty much a remake of Apocalypse Now in space. Famously, Apocalypse Now was a loose adaptation of Joseph Conrad’s seminal Heart of Darkness, and has become almost a storytelling genre unto itself. A man undertakes a dangerous mission of a personal nature through a mighty and dangerous quest to have some kind of fateful question or quest answered; here, Brad Pitt plays an astronaut seeking an absent father at the very end of the solar system to ask why he left. In the past, Jame Gray’s films have left me either asleep (The Yards) or angry (We Own The Night) but I’m pleased to say that Ad Astra, the director’s Kubrikian cosmic escapade, is actually really rather decent.

In the near future, the world has embarked upon a militaristic conquest of our nearest celestial bodies, namely the Moon and Mars, and has established colonies on both. It’s here we meet US Space Command Colonel Roy McBride (Pitt), who is tasked with a mission of the utmost secrecy: to send a message to his long distant father (Tommy Lee Jones) aboard an exploratory spacecraft known as the Lima Project, dispatched years earlier to locate the existence of extraterrestrial life beyond our solar system. Roy must travel from Earth to the Moon, and there board a rocket to Mars, in order to send a laser signal to Neptune, where it is believed the Lima Project is; the Earth is being struck by increasingly destructive energy blasts, said to be emanating from the anti-matter core of the Lima Project’s engines, and Roy must somehow get his father to turn off the switch and save the galaxy. Naturally, he isn’t told the entire truth, and is secreted aboard a desperate rocket launch to Neptune in a last-ditch effort to destroy the spacecraft before it destroys us all.

The obvious comparison to Ad Astra is Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, the film by which all “realistic” space travel sci-fi is measured. Indeed, Ad Astra is borderline OCD when it comes to depicting what we know, expect and reasonably assume about space flight, particularly long-haul space travel between planets. James Gray has crafted a film that feels both lived-in and fantastic, using predictions about technology and science to anticipate how humans might eventually journey further beyond the moon inside our lifetimes. It borrows a little from 2001, a little from Christopher Nolan’s Interstellar, and a smidge from Ridley Scott’s recent The Martian, in giving us accurate-to-the-minute details on how spaceflight might operate into the future. This exquisite world-building is merely the canvas for Brad Pitt’s Roy McBride to engage with his complex emotional journey to locate his missing father, and even if you don’t find the story or characters particularly engaging the scenery and attention to detail is nothing short of sublime.

Gray, who directs from a screenplay he co-wrote with Ethan Gross (Fringe, Klepto), finds much humanity to mine within this cosmic odyssey. The central character is a man of restrained physiognomy (his heartrate never goes above 80, exclaims one science boffin early in the film, ensuring we’re aware of Roy’s proclivity for calm under extreme duress) and melancholy bearing; McBride’s estranged wife is played by Liv Tyler in a role best described as an honorific cameo, whilst his friends are counted on the remaining fingers of one hand. The fact that McBride’s father is the “legendary” space hero Clifford McBride weights heavily on his mind, burdened by expectation and the sense of profound loss at his father’s absence. It’s an interesting internal conflict that forms the crux of Ad Astra’s human narrative, and one I think invests Pitt’s doe-eyed performance with as much intimacy and stoic internalisation as I think he’s capable of; it’s not Pitt’s best ever performance but it’s one that taps into his sense of quiet solitude and introspection, something he’s very, very good at. Outside of the McBride arc, the rest of Ad Astra’s story seems dull and uninteresting by comparison. The supporting characters exist to help McBride go on his journey, and do very little else other than give exposition or propulsion to the film’s endgame.

As he has in the past, Gray has gathered an excellent cast to help tell his story. Donald Sutherland portrays the former friend of Cliff McBride’s who suborns Roy into service, with John Ortiz assisting in the shot-for-shot remake of Martin Sheen standing in the office listening to Harrison Ford at the beginning of Coppola’s wartime masterpiece. Ruth Negga does solid work in a supremely underutilised role as Mars’ resident commander in chief, the colony boss who aides Roy on his secretive personal journey, while spotting Natasha Lyonne in a minor role doing her shtick was surprising and laughably silly – she stuck out like a sore thumb, which may have been the point. Gray imbues a sense of awe and mystery to his film, awe in the achievements of human endeavour and mystery in the link between father and son across the cosmos – hell, it’s a little like Nolan’s Interstellar in this respect, only a little less embracing. The entire time I was watching I kept thinking of similar thematic material in Apocalypse Now, particularly the journey upriver (ie, into the outer reaches of unexplored space) to find Colonel Kurtz only to discover madness and death. Ad Astra’s climax is far less circumspect and controversial, with Tommy Lee Jones’ Clifford McBride nowhere near as psychotic as Brando’s Kurtz ever was, and the film veers wildly into paternal loss and grief through its obligatory “stargate” hallucinogen sequence (Roy has nightmares/flashbacks on the journey between Mars and Neptune, a voyage of some billion or so miles). Does it work as well as it could? No, the climax between Pitt and Jones is something of an anticlimax, all things considered, which was a bit annoying, but the journey and revelatory nature of Pitt’s characters’ emotional state was worth the trip.

Filmmakers often turn to the vast reaches of space to paint intimate pictures of the fragility and smallness of life, how our problems as a species seem indifferent to the vast gulfs of nothing between our world and every other. Ad Astra dips a toe into this subtext, throws a couple of decent action sequences into the mix (a thrilling chase across the lunar surface is well done, maintaining the “realistic” tone of space travel with the “pew pew” of people firing last guns in the vacuum of space) as well as some moments of abject terror (one of the shuttles answers a mayday from a vessel in distress, which turns deadly after a few moments thanks to a violent still-alive simian) to provide one of the least offensive humans-in-space postulates in more than a while. The film asks questions but doesn’t answer then sufficiently enough to make a truly rewarding experience, but the journey is progressively masterful despite this deficit in payoff. I’d wager the film utilises genre tropes to shorthand its message and complex human ideals, but it does so without drawing attention to them in an overt manner.

Ad Astra is a restrained, nuanced examination of a man’s journey into the cosmos; analogous to the human soul, we find his journey torn between duty, family and grief, perhaps even anger that Pitt’s layered performance keeps from bubbling over. Gray’s direction is excellent, the acting altogether excellent, and the visual effects are of an exceptionally high calibre. Almost derailing the film is a script that leans too heavily into ponderous Malickisms; sonorous voice-overs that offer piffling pseudo-psyche nonsense and indifferent internal monologuing for the central character, the kind of eye-rolling garbage foisted upon the world by Terrence Malick. But it’s an otherwise engaging, enthralling piece of scientific fiction that works often in spite of itself. Rewarding human complexity is difficult to pull off, even moreso in outer space (anyone remember Danny Boyle’s Sunshine?) but James Gray has achieved a notable reworking of a classic quest story that is eminently effective almost all the time. Venture into its reaches with my assured recommendation.