Movie Review – Hunchback Of Notre Dame, The (1923)

Principal Cast : Lon Chaney, Patsy Ruth Miller, Norman Kerry, Kate Lester, Winifrid Bryson, Nigel De Brulier, Brandon Hurst, Ernest Torrence, Tully Marshall, Harry von Meter, Raymond Hatton, Nick De Ruiz, Eulalie Jensen, Roy Laidlaw.

Synopsis: In fifteenth century Paris, the brother of the archdeacon plots with the gypsy king to foment a peasant revolt. Meanwhile, a freakish hunchback falls in love with the gypsy queen.

********

In April 2019, the Notre Dame cathedral in Paris, arguably France’s most iconic landmark behind the Eiffel Tower, suffered significant damage after a massive inferno broke out, destroying the structure’s roof and sections of its ancient interior. The event catapulted interest in the building to the forefront of public imagination, an imagination popularised by the ongoing mystique of the famous Hunchback of Notre Dame, an olde-timey story written by Victor Hugo and set in the eponymous building. With the Disney film version of Hugo’s novel easily the most identifiable exponent in modern times, it falls to me to revisit several of the older cinematic takes on the acclaimed Gothic novel, first published in 1831 (nearly 2 centuries ago), beginning with the first full-length feature, 1923’s silent classic starring Lon Chaney and Patsy Ruth Miller.

Paris: 1482, and in the central cathedral of Paris, Notre Dame, a half-deaf, deformed hunchback named Quasimodo (Chaney) works as the building’s bell-ringer. The archdeacon, Dom Claude (Nigel De Bruller) is a good man, whilst his brother, the evil Jehan (Brandon Hearst) controls Quasimodo’s life with hatred and rage. One night, Quasimodo is tasked by Jehan to kidnap the beautiful adopted gypsy daughter of Clopin (Ernest Torrence), Esmerelda (Patsy Ruth Miller), in order to woo her. Although the kidnap is foiled by Captain Phoebus (Norman Kerry), Esmerelda becomes the object of affection and inevitably, unwittingly, stirs lust among local men to the point where she requires sanctuary inside the cathedral, and assistance from the tragic hunched figure in the shadows.

The production of Chaney’s Hunchback venture is something of a jigsaw puzzle. Chaney himself had long desired to play the role of Quasimodo, and the film’s genesis really began some ten years earlier, when the actor acquired the rights to turn Hugo’s novel into the first feature film to bear its name. Legendary producer Irving Thalberg reputedly wanted the film to be a “prestige” production of note, and convinced Universal’s founder Carl Laemmle, to approve the expensive outlay. It is reported that this silent film cost Universal somewhere in the region of $1.2m, (or around $17m in today’s money), which would have been quite an ask for bank approval in the day. The studio would recreate the streets of ancient Paris in exacting detail, as well as the interior of the vaulted cathedral, on the studio backlot in California, and signed then-Paramount-owned director Wallace Worsley to direct. Both cinematography and score are credited to numerous contributors, while the film’s editorial credits are also extensive for a project of this vintage. It should be noted that no original film negative of Hunchback exists, with all available prints derived from lower quality 16mm duplicate negatives after the majority of original prints were destroyed by the studio or simply wore out over time. Hunchback would become one of Universal’s most commercially successful silent films, and remain the only version on screen until RKO’s 1939 remake.

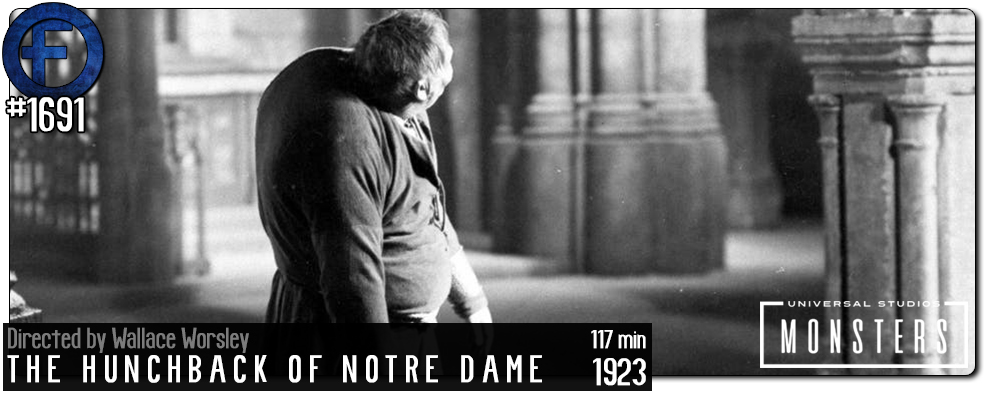

Regardless of provenance, the Chaney version of Hunchback is iconic for a multitude of reasons, notably among them the performance of the cast (including Chaney), as well as the monolithic Hollywood facades replicating the titular cathedral (build full scale on the Paramount lot, along with a clutch of macabre surrounding streets and sewers) that fill the screen at every possible opportunity. It’s a dauntingly epic film production, to be sure, as pure a Gothic horror as might come from the 1920’s, mixed with a mildly laughable tragic romance that feels slight by today’s standards, but offers plenty of indelible imagery to manifest under Worsley’s atmospheric direction. The vaulted ceilings of the cathedral, the eye-wateringly tall facade – complete with the structure’s famous gargoyles and statues – feature prominently, and Chaney’s continued clambering across the exterior of the facade must surely have induced gasps from the audience of the day, such is the realisation that he’s climbing at significant height! Indeed, from costuming to set design, lighting and cinematography, the film feels expensive even now; despite the poor quality of the available print the emotion and energy of the cast and story seep from the screen.

Chaney, as Quasimodo, is electrifying in the role. The actor, noted for performing his own makeup effects throughout his career, is mesmerising as the title character, bug-eyed and monstrous in form and yet maintaining a somewhat innocent clownish feel engendering sympathy. Chaney’s affectations and over-the-top performance style might feel outdated but he still brings a truly heartbreaking sense of tragedy to the forlorn, disfigured creature. For her part, Patsy Ruth Miller is roundly excellent as the center of everyone’s affections; as Esmerelda she personifies the good and moral center of humanity, beset on all sides by the lecherous Parisian underworld and the frivolous aristocratic elite, all of whom stake their claim upon her beauty and youthfulness. Miller isn’t a wilting flower, mind, and offers certain femininity and strength of character to her role, and the subtle, dangerous hint of sexuality (she’s frequently garbed in thin costuming or bound and grappled by muscular men…) provide allure to this early 20th Century classic. Co-star Norman Kerry, as the lusting Phoebus, is a showboat of masculine handsomeness, while Ernest Terrence’s, Clopin and Brandon Hearst’s sinister Jehan give the film a sense of danger and villainy. Although the acting style is of the period, with considerable hammy facial expressions and a lot of clutching oneself in abject horror/shock/fear, the cast are all uniformly excellent in their respective roles and bring emotional heft to the production at all times.

It should be noted that the version of Hunchback for review here is from Flicker Alley: the score is compiled by Donald Hunsbury and Robert Israel, and performed by the Robert Israel Orchestra, and to a degree it’s a seamless blending of action and music. There are moments of the available score that don’t quite match the tone and timbre of the visuals, however, but is probably in keeping with the original musical accompaniment, to the best of my knowledge. Orchestral strains highlight and accentuate the on-screen action as best as possible, veering into hysterically melodramatic moments here and there before returning to the film’s more sanguine musical motifs. Crucial moments, such as an early torture sequence of Quasimodo, as well as the film’s climactic riot before the Cathedral’s massive frontage, and the tragic fate of Quasimodo himself, play particularly well with the music, although a lot of the emotional content transfers solely from the performances themselves.

As with any silent film, you need to be prepared to give the film a solid chance. It’s got plenty of action, romance and dramatic moments of importance, but as with all films of the period they take some acclimation to really savour. The interstitials are by-and-large formulaic and give exposition and dialogue where required, and for a plot-and-dialogue-heavy story like Victor Hugo’s there’s a lot to explain for unfamiliar audiences. Some might find themselves frustrated by the constant intrusion by title cards, and I hesitate to suggest the film could do with less of them, but sometimes I felt the abundance of them here kept the film’s pacing and energy limited in what it could have achieved. That’s just me, though, criticising film techniques from a century ago. Arguably, however, any fan of silent film will remain transfixed by the film’s staggering production design and opulent sense of occasion. Chaney’s makeup is dynamite, the effects utilised throughout the film superbly rendered (the legendary Bastille is rendered as what appears to be a matte painting of some sort) and the performances from all are solid enough to keep the film moving even when the title cards threaten to overwhelm. The Hunchback Of Notre Dame has rarely looked as stunning as this 1923 epic, and despite the ravages of time playing havoc with available film source material, the power of Wallace Worsley’s iconic direction and the studio’s gargantuan spend on set-design enshrine its legendary status, as well as reminding us all of just how great a performer Lon Chaney was in his day.