Movie Review – Cool Hand Luke

Principal Cast : Paul Newman, George Kennedy, Strother Martin, Jo Van Fleet, Joy Harnon, Morgan Woodward, Luke Askew, Robert Donner, Clifton James, John McLiam, Andre Trotter, Charles Tyner, JD Cannon, Lou Antonio, Robert Drivas, Marc Cavell, Richard Davalos, Warren Finnerty, Dennis Hopper, Wayne Rogers, Harry Dean Stanton, Ralph Waite, Anthony Zerbe, Buck Kartalian, Joe Don Baker.

Synopsis: A laid back Southern man is sentenced to two years in a rural prison, but refuses to conform.

********

Rough, ragged and featuring an all-star cast, Stuart Rosenberg’s 1967 prison drama Cool Hand Luke remains an enduring classic of the genre and boasts two award-worthy performances from Paul Newman and George Kennedy, the latter of whom would win an Oscar for his role. Masculine, sweaty, pulsating with unresolved sexuality and a violent underbelly, Cool Hand Luke feels like the progenitor of many an imprisoned men narrative, from which we draw modern classics such as Shawshank Redemption, O Brother Where Art Thou and even Toy Story 3. Okay, maybe not quite Toy Story 3. At times corny, at times demonstrably powerful, and even occasionally euphoric, Cool Hand Luke feels like it was made by the very men it depicts, hewn from jagged film stock and thrown together whether it likes it or not.

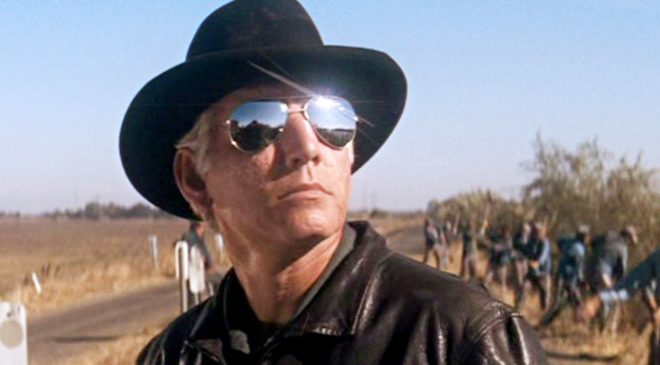

Former war veteran Lucas “Luke” Jackson (Newman) is arrested for cutting the heads of parking meters in a drunken frenzy. Sentenced to two years prison, he is sent to a Florida chain gang to work repairing and maintaining the states extensive road network. The prison is run by a stern warden, the Captain (Strother Martin), and his underlings Boss Paul (Luke Askew) and the sunglasses wearing Boss Godfrey (Morgan Woodward). Luke’s laid-back persona makes him popular with his fellow inmates, including prison leader Dragline (George Kennedy), who sees in Luke something of a kindred spirit. As Luke’s time in prison starts to wear him down, he makes increasingly desperate escape attempts, none of which succeed for long, and he spends more time in “the box” – solitary confinement – for his efforts.

Cool Hand Luke is nothing of not incredibly influential. Iconography from this film has popped up in modern cinema ever since – notably, the silent, menacing Boss Godfrey archetype in the Coen Brothers’ O Brother Where Art Thou, the harsh punishments bordering on sadism in Shawshank Redemption, and Clifton James’ memorable “….gets a night in the box” monologue popping up as a homage in Toy Story 3. See, I told you Toy Story 3 was influenced by this film! Written by author Donn Pearce (from his own novel) and co-scripter Frank R Pierson, Cool Hand Luke’s story of incarcerated friendship and purposeful freedom-driven subtext taps all the dot-point notations of a quality prison movie, including the cruel warden, the crueller guards, and the fraternal sense of communal hope by the inmates, all of whom represent the stock-standard ensemble of representation (save one – there are no black inmates in this film that I noticed, take that as you will). It’s a well written film, regardless of your thoughts on the direction, and the ensemble deliver generally across-the-board solid work bringing even the secondary characters to life in a believable way. A glorified cameo by Jo Van Fleet, as Luke’s dying mother, hammers home the loss and lament of a time when disenfranchisement wasn’t just an African-American problem, it was a national problem for all. The battle between Luke and his desire to escape, and the warden and his gang of guards’ desire to break these men into indentured slavery, doesn’t feel like the focus of the film for its first half, with the story taking a long time to develop the keen friendship between Luke and Dragline and the sense of hope Luke brings to the prison. The script works best when it’s telling the story of the characters, rather than taking time to be nasty or cruel, such is the dichotomy of any prison movie, really.

I often find these movies to be a little heavy on the sugar regarding the motivations for all involved: we’re meant to feel sympathy for the plight of these men due to their happy-go-lucky nature and the sheer spitefulness of those guarding them, but you have to remember that the men in prison are criminals. They are there for a reason. Sure, ripping parking meters apart and taking the coins perhaps doesn’t warrant 2 years of hard time by modern contexts; nevertheless, the warden himself even indicates that some of the inmates in the Floridian prison camp are there for extended stretches, and have some hard currency against them. As we gravitate to the plight of Luke, Dragline, and the wider ensemble of inmates we meet, and find their treatment by Boss Paul, the more sympathetic Boss Shorty (Robert Donner) and the others (including John McLiam, Andre Trottier and Charles Tyner) to be increasingly vile and inhumane, we need to remember that the men involved – Luke included – have committed crimes against which they need to pay back. The film seems intent on making us like Luke’s laid-back, she’ll-be-okay attitude to the point we’re rooting for him to escape to freedom, but Cool Hand Luke isn’t that kind of movie. It’s a hot, humid, sticky mess of masculine hopelessness and Christian allegory, cast against the dusty landscape of hellish roadways across the state’s rural byways.

Newman, as Luke, personifies the American ideal. He’s superficially not fussed by being in prison, and becomes idolised for his laissez faire attitude by his fellow inmates, none moreso than Kennedy’s irascible Dragline, the leader amongst the prisoners. Recalcitrance is beaten out of the inmates, who must acquiesce to their captors with constant referrals to “the bosses” and a regimented routine of existence. Luke, who seems indifferent initially to the harsh prison lifestyle, eventually confronts Dragline in a hot afternoon boxing match – Dragline beats Luke to a pulp, but Luke refuses to acknowledge defeat, eventually forcing Dragline to walk away in disgust at his own belligerence. This action forces Dragline to recognise the difference in their outlooks, and the older man sees in Luke a chance for some kind of redemption in the despair he faces daily. Luke is depicted as some kind of moral saviour to the inmates, a Christ-like resistance to authority similar to that of Jesus and the Jewish Elders of his day. At one point, Luke’s spirit appears broken after being forced to dig, fill in, and then re-dig a grave-like pit in the prison yard after a solid day on the chain gang, almost a personable crucifixion in many ways, and with his brokenness comes a sense of despair for his fellow inmates, whom recognise their own futile futures inside the prison. Newman’s screen charisma is full-throttle here, creating in Luke a quiet and unassuming man learning to accept the reality of his past, and against Kennedy’s brusque Dragline the pair make quite a team. It’s no buddy-comedy but their is a legitimate friendship in their on-screen pairing, much like that between Morgan Freeman’s worldly-wise Red and Tim Robbins’ innately good Andy Dufresne in Shawshank Redemption. Kennedy rightly snagged an Oscar for his work as Dragline, he’s really, really good, while Newman was nominated for his work (he lost to eventual Best Actor Rod Steiger, for In The Heat Of The Night) as Luke in a role that is truly indelible. Has there ever been a more perfect role for an actor of Newman’s considerable charm and ability?

The supporting roster is truly, truly remarkable. Keen-eyed viewers will spot future Alien actor Harry Dean Stanton (here credited simply as Dean Stanton), a young Dennis Hopper, a young Joe Don Baker, and a young Anthony Zerbe, as inmates alongside Newman and Kennedy. Joy Harnon makes a brief but incredibly memorable cameo as a young woman washing her car in plain view of the working chain gang: her allure is enhanced by the proximity of water and soapy bubbles, and her obvious physical prowess with… er… a hose and a sponge. Morgan Woodward makes his mirror-glasses prison Boss a truly menacing figure of casual violence and sadistic mind-games, and Strother Martin’s iconic line delivery as the prison warden remains a key feature. In truth, nobody puts a foot wrong in terms of performance, all inhabiting their roles and bringing a real sense of truth to the harsh, depraved nature of their situation.

It’s the direction of the film itself that many might stumble over. Directed by then-relative newcomer to cinema Stuart Rosenberg, Cool Hand Luke is a movie that feels somewhat like a student film than a big-budget studio drama. The photography appears fraught with overexposure and a grainy, low-budget ruggedness that in most cases works for the story, a heat-blown warmth to the colour tone that accentuates the hellish conditions the men must all work in. Some of the framing, angles and editing feel incredibly rough, focus issues and jagged rack-zoom handiwork creating a sense of either a rushed editorial process or problematic on-location shoot at some technical level: personally, I think the film works due to its more obvious technical flaws and failings, the legendary cinematographer Conrad Hall’s magnificent framing remaining mired by Rosenberg’s less-than-subtle editing and choice of shots. The violence of the film is sporadic, and usually limited to theatricality rather than realism, save for the film’s climactic moments in which Luke is shot by Boss Godfrey in a truly shocking manner, while the language and depiction of rural American life at the time approaches a nostalgic nihilism. The imagery and subtext of the film isn’t subtle, and the use of songs to elicit more of that allegorical underpinnings works well; Cool Hand Luke is one hot-tin-roof movie.

Undeniably a classic for a multitude of reasons, Cool Hand Luke boasts two genuinely great leading performances and an archetypal modern prison drama foundation. Newman’s performance is excellent, Kennedy’s even moreso, and the sense of bondage and freedom of prison life against a sweaty, hot-stew Florida sun is palpable: you feel grimy just watching it, it’s so raw and gritty. Although showcasing a limited technical quality (in my opinion) the film’s strength lies in its characters, good and bad, and for that it’s most definitely a great film.