Movie Review – Intolerance

Principal Cast : Lillian Gish, Mae Marsh, Robert Harron, Fred Turner, Miriam Cooper, Walter Long, Tom Wilson, Vera Lewis, Sam De Grasse, Lloyd Ingraham, Ralph Lewis, Margery Wilson, Eugene Pallette, Spottiswoode Aitken, Ruth Handforth, Allan Sears, Josephine Crowell, WE Lawrence, Constance Talmadge, Elmer Clifton, Alfred Paget, Seena Owen, Tully Marshall, George Siegmann, Carl Stockdale, Howard Gaye, Lillian Langdon, Bessie Love, George Walsh, Mary Alden, Todd Browning, Donald Crisp, Douglas Fairbanks, Harold Lockwood, Erich von Stroheim, King Vidor, Francis McDonald.

Synopsis: The story of a poor young woman, separated by prejudice from her husband and baby, is interwoven with tales of intolerance from throughout history.

*****

This review is based on the 177 minute Digital Cinema Restoration Cut, one of four versions of Intolerance known to exist. This version of the film premiered in 2007.

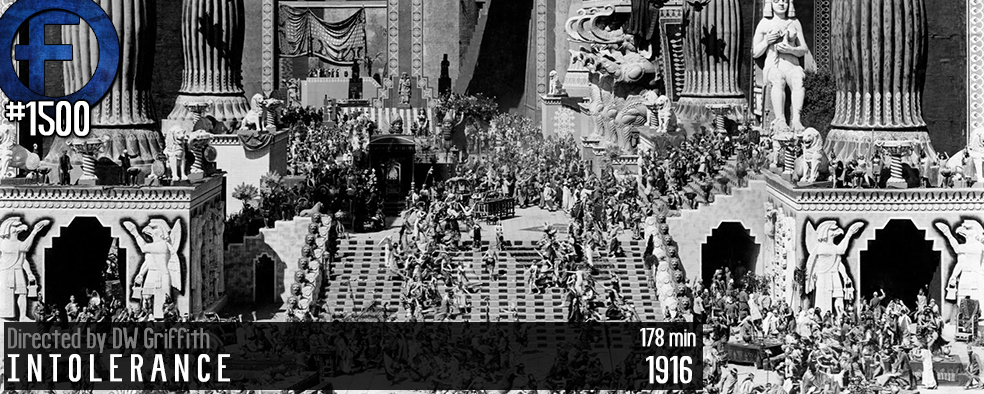

Gargantuan, sprawling, mesmerising: DW Griffith’s 1916 silent film epic is an astonishing work of narrative fiction and a bold, undiminished visual masterwork, tempered only by prevailing social norms and cinematic technicality, and stands alongside the greats of cinema as an all-timer to beat most all-timers. Boasting a literal cast of thousands, Griffith and his production team spared no expense in bringing Intolerance to the screen, with no less than 6 writers (including Dracula director Tod Browning, also appearing in a minor on-screen role, and Gentlemen Prefer Blondes writer Anita Loos) credited and one of the most lavish canvases on which to put their story. The film stakes its claim as a testament to the power of love, or rather love overcoming intolerance of a kind, and manifests through a quartet of varying quality narratives traversing the centuries to deliver exactly that.

In turn-of-the-century America, a young girl, the Dear One (Mae Marsh) falls for local miller boy (Robert Harron), although they’re sent to the city following a worker’s strike empties the factory. Falling into crime and destitution, their love burns despite being kept apart by people’s prejudices. In ancient times, wars rage between the King of Persia (George Siegmann) and Prince Belshazzar (Alfred Paget) of Babylon, and the fate of a young mountain girl (Constance Talmadge) hangs on people’s prejudice, while the city’s fall is precipitated by the actions of opposing religious ideologies. In biblical times, the actions of Jesus Christ (Howard Gaye) – miracles and subversion of the Pharisees’ decrees – bring about the Lord’s crucifixion. And in Renaissance France, religious intolerance leads to the St Bartholomew’s Eve Massacre when the Huguenots and Catholics clash in heated belief.

It’s hard to believe a film like Intolerance, over a century after debut in 1916, remains so prescient and powerful without feeling out-of-time. Indeed, DW Griffith’s follow-up film project after The Birth of A Nation is testament not only to the director’s storytelling prowess but his acuity in achieving something genuinely great – Intolerance is a work of art – and establishes himself as one of the pioneers of his medium, ever. Often intimate and beguiling, equally magnificent and operatic in scope, Intolerance’s choice of time periods and political characterisations of each era feel saturated in belief of their inherent truth. Griffith and his writers weave a magnificently honed and eloquently filmed thread of human suffering, violence and hope through the film’s quartet of arcs, felt most keenly in the Babylon-centric narrative and the “present day” one, set in 1914. Human prejudice can be a frustrating and angering thing, and Intolerance has moments that writ this legacy large upon the screen. Make no mistake, Griffith has something to say here, and he says it well.

The central characters, Mae Marsh’s enthusiastic yet tragically besmirched Dear One, and Constance Talmage’s ferocious Mountain Girl, lead the parade of ensemble cast with excellent screen chemistry and a sense of romanticised melodrama. They’re abetted by the likes of Robert Harron’s scallywag leading man, Frank Brownlee’s curmudgeonly older brother to the mountain girl (nope, barely anyone in this film has a traditional name, which was Griffith’s way of making each character a personification of human aspects, rather than a specific person…) and the various sidebar and supporting ensemble players scattered throughout. Keen-eyed observers might also spot prolific actress Mary Adlen, Donald Crisp (who would also appear in Griffith’s later film Broken Blossoms), Douglas Fairbanks and legendary actor-director Erich von Stroheim (Foolish Wives, Greed), among others cameoing here. A virtual who’s-who of silent film era stars populate the film, some barely recognisable in period outfits. While the acting in Intolerance perhaps isn’t its most prominent facet, nobody here does anything untoward while furthering the story and inhabiting the characters they play: Griffith directs his massive roster of actors with wit, tragedy and empathy, and crafts his story within the frame of his camera.

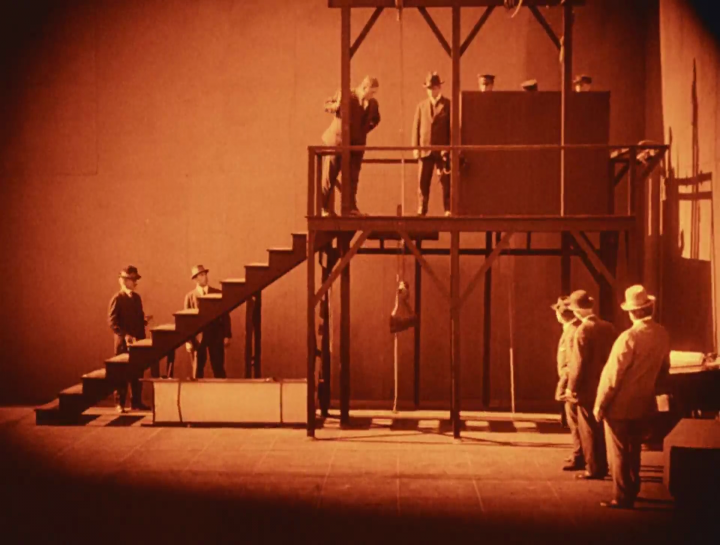

Intolerance does something few films of the period attempted: it cross cut between different time periods. Filmgoers were used to inter-spliced narratives between characters, but rarely (if ever) had a film woven in different characters and different periods in time before. Griffith, in doing this, brought tension to the movie, enabling the audience to feel the parallel themes of each of the four sub-stories, magnifying each and making the whole so much more potent. The film’s glorious cinematography sparkles in the 2007 restoration, maximising the effect of Griffith’s use of vignetting his shots the entire way through to ensure we focus on a specific thing in each frame. It’s an interesting technique, and one employed a lot within the silent era, but I’ve yet to see it handled so perfectly as Griffith does here. Griffith packs so much into each angle and shot, slipping easily between wide and closeup to energise the story and keep audiences locked to the screen. The film is also tinted in numerous shades, most prominently sepia and red/pink, although blue and yellow manifest where appropriate for either the mood of the film or the time and location of the story. I find this kind of thing a little hard to become accustomed to, but having seen it done so superbly with Abel Gance’s Napoleon I’m prepared to accept its charms.

Chief among the film’s most memorable elements is its sheer size. The original cut of the film was a hefty 210 minutes, a bladder-stretching time for silent film audiences and even today a considerable viewing commitment. Few films deserve such length, and even fewer reward the viewer for their persistence, but Intolerance is one of those that both needs and deserves such breadth of scope and cinematic largess. Opulent is a word I’d use to describe many of Intolerance’s enormous sequences, particularly the Babylon setpiece which includes an enormous walled facade that stands many stories high and is as imposing as the film’s length. Little wonder it stood for years after production wrapped and was eventually homaged in an actual building in present-day Los Angeles.

The film’s centrepiece is the incredible battle between the armies of Cyrus and Belshazzar, a violent, magnum opus of a sequence that is staggeringly brutal and handsomely mounted – I glimpsed some cool flame-throwing war tanks inbound and by God did that do some damage! Giant destruction and enormous battle sequences, as well as clever in-camera split-screen visual effects, not to mention the many hundreds of extras used to portray the various events herein, look expensive even by today’s expectations, and there’s little here to refute the claim that Intolerance is among the most expensive films ever made (estimates put the production cost of this film at around $2.5m, or $48m in today’s money, a staggering cost for a film made in 1916) that would send Griffith’s production company into bankruptcy. It’s a film of expense and nothing spared, a film that spans centuries and compiles some bravura production design and editorial prowess that – while not appealing to audiences of the day – certainly feel effective even now. My goodness, the entertainment!

Intolerance is a remarkable film achievement, and certainly one any devotee of silent cinema can overlook. Thematically it’s dynamite, touching on a variety of prejudicial elements of human history and showcasing them in all the opulence and big screen thrills film of the era could provide. The acting is on-point, the production design unrivalled in every sense, and Griffith’s editorial choices holding the four stories together as they build towards their emotional and resonant climaxes mark the film as not only an icon of the period but a genuine classic of the medium’s history. Breathtaking sets and simply epic action sequences are spliced into moving and eloquent (and complex) dramatic moments, coupled with exquisite costume design and cinematography, make Intolerance a film experience not to be missed. Exceptional in almost every sense, Intolerance is the very definition of must-see.