Movie Review – Safety Last!

Director : Fred C Newmeyer + Sam Taylor

Year Of Release : 1923

Principal Cast : Harold Lloyd, Mildred Davis, Bill Strother, Noah Young, Westcott Clarke, Earl Mohan, Mickey Daniels, Anna Townsend.

Approx Running Time : 74 Minutes

Synopsis: When a store clerk organises a publicity stunt, in which a friend climbs the outside of a tall building, circumstances force him to make the perilous climb himself.

******

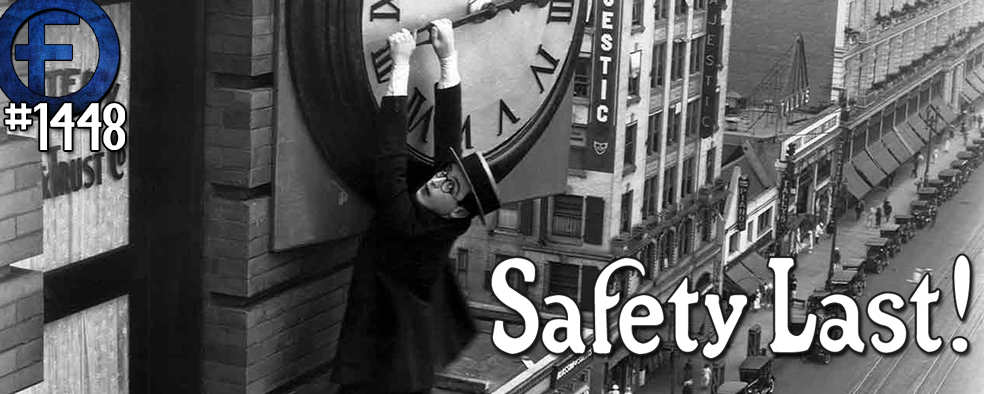

Safety Last! is the iconic silent film starring early Hollywood contemporary of Charlie Chaplin and Buster Keaton, Harold Lloyd. Lloyd, a far more prolific film producer than either Chaplin or Keaton, and in terms of box office overall a more successful one, made his name in Hollywood with his bespectacled “glasses” character, an enthusiastic go-getter which suited the Roaring 20’s of America’s globalist expansion, and this film is the oft-cited champion and most popular exponent of his output from the day. It’s the film from which we draw one of the most famous images in all of silent film, that of Lloyd dangling precariously from the broken clock-face atop a Los Angeles highrise, and while the film is more than just this thrilling moment on screen, there’s few better examples of silent film’s consummate ability to craft comedic moments that thrill audiences.

Lloyd plays a young haberdashery clerk who’s come to the big city to make good, so as he can marry his small-town sweetheart (Mildred Davis, Lloyd’s eventual real-life wife). Although his career takes an abrupt turn when he decides to hold a skyscraper climbing publicity stunt with his Pal (real life human fly, Bill Strother) the main competitor, as a way to get money to set up a home with his gal.

Idealism and virtue are the order of the day for Safety Last!, a cleverly mounted silent “action” film that spends a large portion of its first half setting up the plot before revealing its brilliantly climactic highrise climb sequence. Lloyd’s All American hero – unnamed, but various sources indicate the character was also named Harold – is crisply defined and eminently enjoyable, trying to prove his worth to Davis’ romantic interest, while also having to avoid local LA cop (Noah Young) alongside Strother’s accomplice character. The film’s climactic ascent to the top of an LA skyscraper is played like a protracted Looney Toons short, farcical and spliced with clever (and not-so-clever) asides with supporting actors, and in truth this is the film’s real strength.

The film opens with a sombre note, of Lloyd’s character seemingly heading towards a hangman’s noose before the camera reframes and we see him stepping onto a train station platform and heading off to the big city. It’s a weird way to commence a lighthearted movie and at first I kinda wondered if I was watching the wrong movie, but once the manic departure sequence kicks in (Lloyd accidentally takes a woman’s baby off the platform instead, lols) the story and plot take second place to the central character’s comedic adventures. As with both Chaplin and Keaton, the major stars of silent film had established screen personas they took with them to each film, and Lloyd’s bespectacled waistcoat wearing protagonist appears honed to perfection. His wide-eyed idealistic nature, his sense of playful fun without being mean, and his apparent disregard for the laws of physics and personal safety (hence the title of the film) make him an endearing, if diffident, hero.

There’s a lengthy slapstick sequence involving Davis’ innocent romantic lead arriving at Lloyd’s place of work, unaware he’s merely a haberdashery clerk and not the general manager, with Lloyd having to pretend his seniority before fellow colleagues whilst avoiding the respective authority figures (Westcott Clarke, as the store’s uppity floor walker, is a delight) in what is the film’s most accomplished amusement moment. The addition of real-life building climber Bill Strother, in his only feature film role, as Lloyd’s buddy, lends an air of credibility to the wide shots of “Harold” climbing various Los Angeles landmarks, but the character actually spends the entire film running from Noah Young’s insistently persistent policeman. Sure, there’s good-natured gags, and plenty of avoidance humour mixed with the chase sequences, and the physical comedy aspects of the film are first rate, but you’re watching this film mainly for the climactic climbing sequence and I’m here to tell you, Safety Last! doesn’t let you down.

Filmed using trick photography and clever camera angles (as well as several roof-mounted sets to fake the side of a building), Safety Last! is nail-biting in its more thrilling moments towards the end. Lloyd uses every story device he can to make his external ascent as tense as he can, from dogs barking, birds alighting on his head, and even ropes and netting making their way into his climb to try and prevent him achieving his goal. It’s incredibly Chaplin-esque, and works more often than not, although the blithering tunnel-vision trope where a character seems to lack peripheral vision before being clocked on the head by something does become tiresome, even though it’s funny. The way the film cuts between wide shots, close ups and trick shots (the master shot of the character climbing the side of a multi-story building was achieved by Strother dressed like Lloyd, with the close-ups all performed by Lloyd dressed as Lloyd) is excellent, drawing the viewer into the character’s plight and at times making one hold one’s breath. The film’s sheer inventiveness cannot be overstated, and it’s easy to see why this sequence holds up as one of the pinnacles of the silent era.

Safety Last! is bright, shiny Americana at a time when the country was booming. The cinematic shorthand employed by Lloyd and directors Fred Newmeyer and Sam Taylor is vintage period stuff, and the film’s energy and vivacity, as well as the many, many funny moments, legitimise it as one of the silent era’s greatest exponents. A deserving classic, and a roundly hilarious movie. Great stuff.