Movie Review – Once Upon A Time In The West

Principal Cast : Henry Fonda, Claudia Cardinale, Jason Robards, Charles Bronson, Gabriele Ferzetti, Paolo Stoppa, Keenan Wyn, Frank Wolff, Lionel Stander, Woody Strode, Jack Elam.

Synopsis: A mysterious stranger with a harmonica teams up with a notorious desperado to protect a beautiful widow and her land from a ruthless assassin in the employ of a railroad tycoon.

********

One of the most influential Westerns ever made, and arguably one of the best exemplars of cinema in general, Once Upon a Time in the West, directed by Sergio Leone, is regarded by modern filmmakers as one of the touchstones that turned them into directors. When the likes of Quentin Tarantino, George Lucas and Martin Scorsese name-drop the film as an inspiration to their own careers, you know you have something very special at work here; although it has dated a little, the technical and narrative proficiency at work with Leone’s bona fide classic is as strong today as it was on release in 1968. It’s the kind of film I wish I was able to make myself; were I a director I’d hold this up as the pinnacle of the artform in the way I’d imagine it. Widescreen cinematography in which every frame is a piece of art, stunning tension elevation through sublime editing, and a terrific ensemble working with a visual master — Once Upon a Time in the West isn’t just a movie, it is — as the kids say these days — cinema.

Plot synopsis courtesy Wikipedia: Once Upon a Time in the West unfolds against the dying embers of the American frontier, where the arrival of the railroad signals both progress and ruthless opportunism. When widowed settler Jill McBain (Claudia Cardinale) arrives in the desert town of Flagstone to find her new husband and his children murdered, she becomes entangled in a bitter land dispute involving crippled railroad baron Morton (Gabriele Ferzetti) and his cold-blooded hired gun Frank (Henry Fonda). Circling this conflict are two enigmatic drifters: the taciturn, harmonica-playing gunslinger known only as Harmonica (Charles Bronson), who harbours a deeply personal vendetta, and the charming outlaw Cheyenne (Jason Robards), whose shifting loyalties complicate the struggle for survival. As alliances form and betrayals simmer beneath Leone’s operatic widescreen vistas, the fate of a single parcel of land becomes the fulcrum upon which vengeance, greed and the twilight of the Old West precariously balance.

From its near-wordless opening quarter hour, inimitable for the arrival of Charles Bronson’s Harmonica and the ambush laid by a trio of hired guns, through to the cultural smashing of nostalgic Old West and post-western modernity as the curtain fades, Once Upon a Time in the West is both a eulogy for a bygone era and a fascinating exercise in the craft of filmmaking. The film’s plot, in which a suddenly widowed frontier woman must survive the travails of omnipresent railroad expansion amid the vengeful denizens of the land seeking to extract the last of their potential, isn’t exactly refreshing these days — the characters are archetypal and the situational plot twists reek of subgenre cliché, although this is less a critique and more just a factual aspect of the production — but Leone, through his cinematographer Tonino Delli Colli and his editor Nino Baragli, crafts one hell of a gut-punch elegy for the genre thanks to captivating camerawork and long, protracted editorial choices that many might find too opaque to matter. To me, however, it matters a lot.

Once Upon a Time in the West isn’t compelling through its inherent narrative, and a lot of the film’s detractors might suggest the story itself is among the weakest elements of it, but I’d argue that the plot, together with the various characters’ motivations and arcs within it, are enough to bolster what is a magnificent opus of style very much being over substance. It runs counter to suggest such story weaknesses exist given names like Dario Argento and Bernardo Bertolucci appear in the credits as having a part to play, but there you have it. The film looks amazing, with the 2018 4K remastering making Delli Colli’s crisp visuals and astonishing colour palette absolutely pop. Everything looks so epic, so mesmerising in Leone’s patented widescreen format, filmed in lush Technicolour and presented in a sublime 2.35:1 aspect ratio, you find yourself holding your breath inadvertently whilst watching; it’s so beautiful. I could wax lyrical about the framing and camerawork of this film for hours — every inch of the wide aspect is put to work, from the hundreds of extreme close-ups of various characters to wide establishing landscape and vista shots, including some very busy background extras and long crane movements that look so crisp they could have been shot yesterday. Leone forces his camera — and by extension our eyeballs — to do a lot of work conveying aspects of his story that might not seem too obvious at first glance. The dusty landscape, the flea-bitten Old West towns, the mechanical grind of locomotives and the suddenly punctuative violence within lengthy sequences of relative silence or calm — Leone crafts the film’s rising tension and ants-in-your-pants anticipation with panache and a sure hand.

Coupled with the fantastic cinematography is the editing by Baragli, who from the outset delivers perhaps the greatest opening sequence in all of American cinema — the arrival of Harmonica at an isolated outpost to be confronted by a gang of armed killers, a fifteen-minute buildup of quiet, melancholy brooding and a sense of foreboding that isn’t released until the final shots ring out. The horror of violence, the pain of loss, the withering rage of vengeance and all emotions in between are delivered with metronomic perfection thanks to sublime editorial choices and pacing from Baragli, choosing to showcase some moments with violent excess and offering restraint in others. It’s an exquisite ballet of cutting, and for a film running nearly three hours it demands attention thanks to the quality on offer. When anyone ever asks what my film inspirations are as a filmmaker, I point them to the opening half of Once Upon a Time in the West, and just ask that they pay attention to the editing.

Having said that, it’s a fair complaint to suggest that the film is slowly paced — or just slow, as my wife mentioned numerous times — and I agree with this as a criticism. Yet, the film isn’t designed for the fast-paced entertainment value of, say, Leone’s other spaghetti westerns in the famous Dollars Trilogy. Here, the morbid curiosity of the collapse of the Old West and gradual morphing into a post-colonial age thanks to technology and commercial engagement is enough to satisfy me as a viewer, but I’d be crazy to suggest it will do the same for others; rather, the film’s loping pace and painterly atmosphere make for a gentle, almost paradoxically modern lullaby for a bygone era. Leone doesn’t turn his characters into heroes or villains in the vein of the genre beforehand, although it’s certainly the case that Henry Fonda is an irredeemable asshole here, but rather as archetypes fading into irrelevance thanks to the arrival of the railroad. Morton’s physical disabilities make him an arch-villain stereotype, but he’s somehow softer than a cartoonish bad guy the film’s style might seem to suggest. The slow collapse of the cowboy way of life, the ingratiating and implacable onset of unions, organised workforces and technology, form a mournful poem capturing the sunset of an entire genre — Leone’s triumphantly operatic zenith.

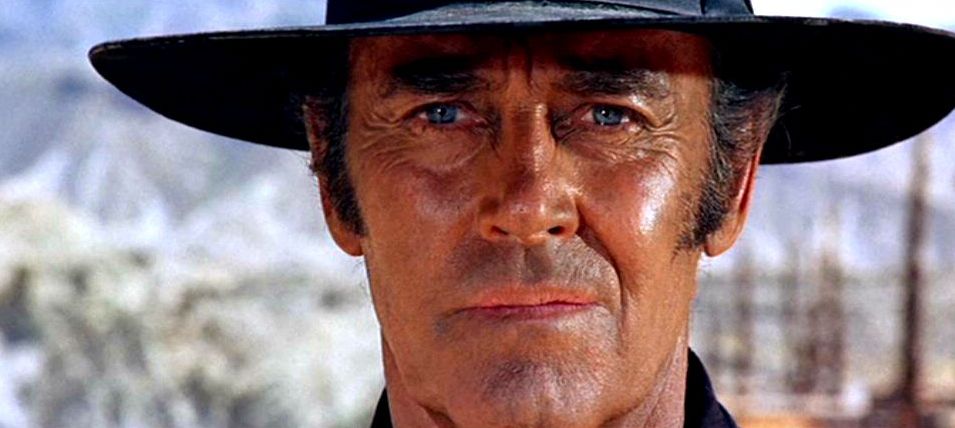

But for a moment, let’s reconcile the stunning technical elements with the equally glorious (and pitch-perfect) cast. Leone’s decision to cast long-time all-American screen hero Henry Fonda into a child-killing, whore-loving asshole is one of the great subversions of a career and screen persona you’ll ever see. Fonda’s flinty glare as he scours the landscape and scowls in extreme close-up is thrilling — an actor who can do more with a clenched jaw than many can with an hour-long monologue. He contrasts well with the more laconic Jason Robards as Cheyenne, a man whose allegiances seem to vacillate depending on who he’s near at any given time. Charles Bronson’s grizzled face is given prominence throughout the film, and while the actor isn’t afforded a great deal of depth to the role, his cool factor is absolutely off the charts. Arguably the weakest acting element is Claudia Cardinale as Jill McBain, although this is perhaps more a concern of direction and writing than performance, as she’s asked to do a lot with conspicuously little, and her character is the least formed of the main quartet. She’s certainly got the looks for the role, the strong-willed ex-hooker turned widow (her husband, Frank Wolff’s Brett McBain, is unceremoniously gunned down by Frank the same day Jill arrives from New Orleans), and I think had she been given more emotional depth than she has here the film’s lynchpin role might have been stronger.

The fourth element of this film that works so superbly is the orchestration of composer Ennio Morricone, who delivers perhaps not the most memorable melodic motifs ever but certainly the most elemental. The film’s music is incredibly dextrous, offering violence, love and grief in equal measure, from its haunting harmonica riff to its soaring orchestral balustrading and emotive vocal accompaniment — Morricone’s score lacks the instantly identifiable melodic motif of The Good, the Bad and the Ugly, but the music here is used sparingly and superbly. And, although perhaps not given enough retrospective recognition, the production designers, costumiers and set designers deserve acclaim for their spectacular work on this movie, giving the film a real weight and depth and sense of place, as well as dusty realism that is only magnified by Leone’s superb lensing.

It’s hard for me to fairly criticise this film when I’ve had an adoring relationship with it for the last thirty years, since I caught it on VHS back in the day. It struck me then as a visual triumph, and in rewatching it now I’m incapable of a lesser argument. It truly is a hypnotically beautiful movie, a near-perfect conflagration of visual design, narrative ambition and production superlatives. In many ways it reminded me of another Fonda film, 12 Angry Men, for its strong technique and mastery of the cinematic form, and although Once Upon a Time in the West may not be quite as potent with its story or characters, it’s arguably the best example of a modern widescreen cowboy movie ever made — if not, it’d have to be in the top five. Once Upon a Time in the West is, in my humble opinion, legitimately a classic and arguably one of the greatest American movies.