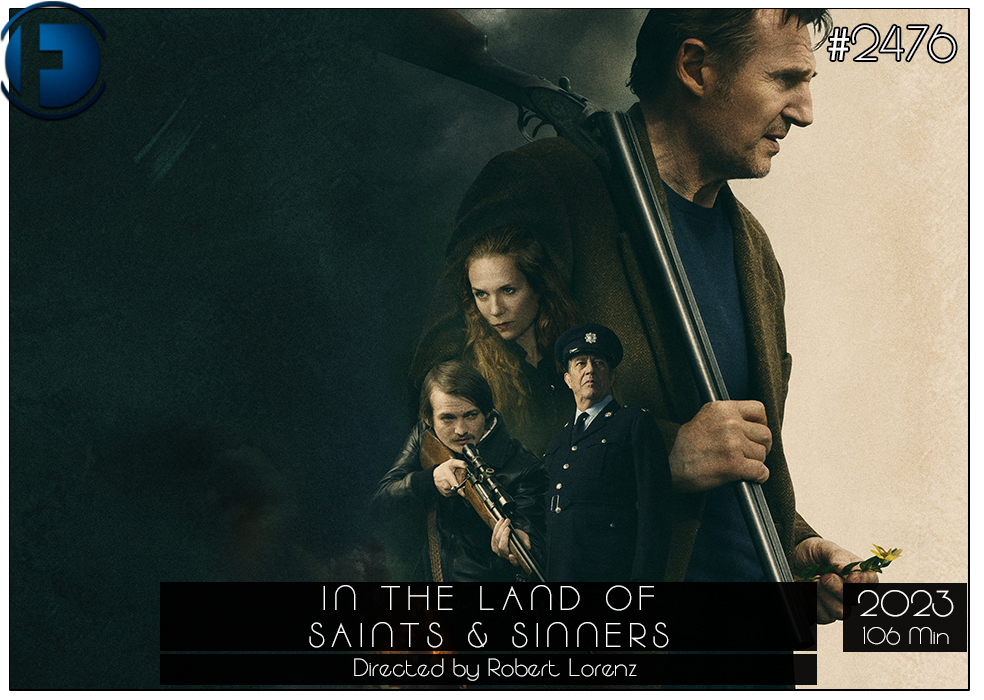

Movie Review – In The Land of Saints & Sinners

Principal Cast : Liam Neeson, Kerry Condon, Jack Gleeson, Ciaran Hinds, Sarah Greene, Colm Meany, Desmond Eastwood, Niamh Cusack, Conor MacNeill, Seamus O’Hara, Mark O’Regan, Valentine Olukogo, Michelle Gleeson, Conor Hamill, Anne Brogan.

Synopsis: A disillusioned hitman comes out of retirement for one last job when an IRA bomber on the run from the law arrives in his sleepy Irish village.

********

The last two decades have been spent idly wondering who plays the grizzled man-of-many-hidden-talents trope better: Jason Statham or Liam Neeson. Given both actors have spent the better part of their careers carving out a niche playing essentially the same character in every film they make, it’s little wonder they’ve become almost synonymous with the action-thriller subgenre. While Neeson’s lead role in In the Land of Saints and Sinners, his second with director Robert Lorenz following The Marksman, won’t be touted among the greatest of his works, it’s still a thoroughly enjoyable, workmanlike shooter with bursts of violence and moments of quiet horror before the bang.

Set in Northern Ireland in the mid-1970s, against the backdrop of IRA violence prevalent in the region at the time, Neeson plays semi-retired contract killer Finbar Murphy, a war veteran looking to hang up his gun. He is friendly with the local Garda, Vinnie (Ciaran Hinds), and several of the village folk, while working for crime boss Robert McQue (Colm Meaney). After a deadly encounter with fugitive IRA bomber Curtis June (Desmond Eastwood), Finbar finds himself firmly in the sights of the young man’s vengeful older sister, Doireann (Kerry Condon), and her associates, who begin tracking him down to exact retribution. Finbar, allied with younger fellow contract killer Kevin (Jack Gleeson), attempts to stave off wanton violence by setting up a rendezvous in town that will unravel his hidden identity and place the people he cares about in grave danger.

In the Land of Saints and Sinners is conspicuously low-key, from its windswept, craggy Irish landscapes and bristling score by The Baldenweg Siblings — Diego, Nora and Lionel — through to its thick dialects and esoteric ensemble character work. It’s as Irish as they come, and spending contemplative time with Neeson, Condon and a cast this good is a genuine pleasure. As an anglophile, it pleases me that a film like this exists, and thankfully, while it sticks rigidly to the ageing hitman-looking-for-redemption archetype, it avoids many of the pitfalls of the modern Hollywood blockbuster. Sure, there’s violence and bloodshed, and a truckload of good old-fashioned profanity, but the film’s quieter, more sombre tone — and Neeson’s grizzled, gruff countenance dominating the screen — makes it feel like wearing a comfortable old jacket: warm and bespoke.

As much as I didn’t enjoy The Marksman — and I really didn’t think much of that Texas-set thriller — Robert Lorenz’s second collaboration with Neeson is a far more circumspect and evocative affair. Neeson’s natural Irish brogue and effortless screen charisma simply work here, alongside old friend Ciaran Hinds as a circumspect local copper. With such solid casting backing up a rich vein of story potential, Lorenz’s job feels half done before he even steps onto the set. Tom Stern’s crisp photography of the County Donegal locations is breathtaking and places the viewer squarely inside the story, while the attention to period detail from production designer Derek Wallace and costume designer Leonie Prendergast ensures the illusion of time and place is never broken. There’s a wonderful symmetry at play — the suspension of disbelief required for small-town Irish village life sitting at odds with Finbar and Kevin’s chosen professions — and that clash of ideology within this bucolic setting is both charming and quietly disarming.

The screenplay by Mark Michael McNally and Terry Loane is unremarkable in its profundity and simplicity, rarely treading ground that feels fresh or somehow different from the rest of Neeson’s modern oeuvre. However, Lorenz and Neeson’s careful build-up of tension — a slow burn of needling menace and imminent danger — proves propulsive enough thanks to the dynamism of the location and the inherent violence we’re primed to expect. When that violence arrives, it’s quick, bloody and jarring, albeit not without flashes of shocking sadness. Neeson does his best with the subtleties, while returning screen presence Jack Gleeson — the ill-fated Joffrey from Game of Thrones — is wonderfully wry as Kevin, Finbar’s younger upstart competitor-turned-associate. Kerry Condon’s ferociously violent Doireann is all spittle and venom, steely-eyed resolve mixed with an almost fanatical love of country, and much of the film’s excitable frisson comes from watching her move ever closer to tracking Finbar down and decimating anyone in her way. Condon doesn’t hold back, though she’s canny enough never to tip into outright melodrama. If I have one chief criticism, it’s that the film doesn’t delve deeply into her motivations for joining the IRA — “fighting for our country” could mean almost anything these days. If you’re of a certain age it carries more weight, but the film doesn’t quite do the work for younger viewers. Had it shaped her into a more empathetic antagonist rather than the somewhat broad villain she occasionally resembles, it might have provided a sharper counterpoint to Finbar’s redemptive arc. That said, Condon is a firecracker here, and the eventual comeuppance — and it does arrive — is dour, perhaps the most dispiriting element of the whole affair.

In the Land of Saints and Sinners is a quietly beautiful elegy for violence set against legitimate natural splendour. I’d be hard-pressed to call it an all-time classic, but it is undeniably a thoroughly enjoyable Irish-set thriller. The cast are uniformly excellent, the plot — when stripped of lush landscapes and tremendous accents — is fairly generic, and Lorenz’s direction is stately, dynamic and unhurried, allowing the film to linger softly with the viewer afterwards. I can understand why some might baulk at its leisurely pace and rural setting, but if you lean into its rhythms and embrace its modest ambitions, there’s a film here well worth your time.