Movie Review – Shane

Principal Cast : Alan Ladd, Jean Arthur, Van Heflin, Brandon deWilde, Jack Palance, Ben Johnson, Edgar Buchanan, Emile Meyer, Elisha Cook Jr, Douglas Spencer, John Dierkes, Ellen Corby, Paul McVey, John Miller, Edith Evanson, Leonard Stong, Ray Spiker, Janice Carroll, Martin Mason, Helen Brown, Nancy Kulp.

Synopsis: A mysterious drifter named Shane (Alan Ladd) rides into a Wyoming valley and becomes entangled with homesteader Joe Starrett (Van Heflin) and his family as they struggle to defend their land against a ruthless cattle baron, Ryker (Emile Meyer), and his hired gun (Jack Palance), embodying the fading code of the Old West.

********

Shane is a film that comes with a lot of nostalgia for me, even if my memory of the film itself isn’t particularly clear. I distinctly recall a time in my childhood, when I was roughly ten or so, when my father – a massive fan of cowboys and Indians as a genre of storytelling – told me that he thought Shane was one of, if not the greatest film ever made. Dad’s western bias notwithstanding, when it eventually screened on local television one day, we sat down to watch it together, and I remember being absolutely affirmed in my father’s opinion that it was a very, very good movie. The best ever? Forgive me, father, for at that point it was either The Last Starfighter or the original Star Wars that held that title, but I always retained fond feelings about Shane as a film, knowing it was a good movie while also serving as a strong bonding memory with my dad.

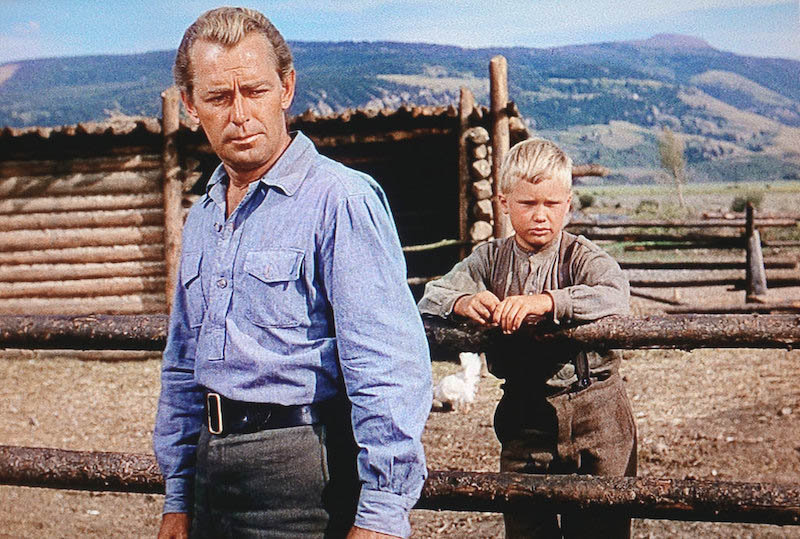

As archetypal Hollywood westerns go, they don’t come much more archetypal than Shane. Set in the late 1880s, the story revolves around a settler family in America’s Wyoming Territory and their conflict with local ranchers who want to push all the homesteaders off their once free-range land. Along comes the mysterious Shane (Alan Ladd), a drifter of sorts whose dark past he tries to keep hidden until the violence becomes too great for him to remain idyllically pacifistic. The family – Joe Starrett (Van Heflin), his wife Marian (Jean Arthur) and their young son Joey (Brandon deWilde) – are the de facto leaders of their small group of settlers, residing near a muddy outpost town where cattle baron Rufus Ryker (Emile Meyer) recruits a dangerous gunslinger, Jack Wilson (Jack Palance in an early role), to run the homesteaders off their properties.

Time hasn’t been kind to Shane’s style of storytelling, with its clunky 1950s editing and restrained violence undercutting much of the potential power of the central character’s dark past. While the majority of the film’s conflict really comes to the fore in the riveting third act – and is steadily built throughout the film thanks to some genuinely brilliant cinematography (shout out to DP Loyal Griggs, who captures the beauty and desolation of frontier America with colourful enthusiasm) – George Stevens’ direction is actually pretty lacklustre, lacking a real sense of showmanship or verve, and giving the film an aesthetic that often feels more made-for-television than big screen. There’s a lengthy barroom brawl early in the film that has some remarkable moments of ferocity, but it’s jarringly edited by today’s standards, resulting in a discombobulated and oddly inert fight that lacks grace or real energy. The climactic showdown in which Shane takes on Ryker and Wilson, and in which the film suggests that Shane may have suffered a mortal wound, is rich with tension but, sadly, again lacks the visual dynamism the script demands.

Having said that, there’s an elegant simplicity to Shane that, despite some wooden acting from many of the supporting players, feels genuinely charming in spite of everything. A.B. Guthrie Jr.’s screenplay, adapted from Jack Schaefer’s 1949 novel, treads a lot of the same ground repeatedly, with the constant drumbeat of everyone’s leaving, but we’re staying from Joe Starrett becoming almost psychotic given the forces working against the farmers. Every five minutes or so, one of the other homesteaders threatens to pack up and leave, and every time Joe has to stand his ground and exhort them to stay. This works the first few times, but tedium eventually creeps in and you start to wonder whether Joe isn’t just a blithering idiot for wanting to remain so stubbornly rooted to the land.

Van Heflin and Alan Ladd are easily the best performers here, despite not being the pair nominated at the Academy Awards – that honour went to young Brandon deWilde and a memorably creepy Jack Palance – and their chemistry together is what ultimately holds the film together. DeWilde has the misfortune of being a fairly weak child actor, and one of my long-standing complaints about screen urchins of this era is that you can see them acting rather than feeling anything remotely naturalistic. It pulls you out of the film when you start noticing the performance for its creakiness rather than its integration into the story. The kid isn’t annoying, thankfully, but he feels heavily coached rather than organically inhabiting the role. The sexual chemistry between Alan Ladd’s Shane and Jean Arthur’s Marian, while never overtly stated, is clearly present but heavily restrained by 1950s moral codes around portraying even implied spousal infidelity on screen. Sadly, this would prove to be Jean Arthur’s final major big-screen role, as she dropped away from Hollywood and retired almost entirely after this film.

The production design is magnificent, to be fair, and perhaps the saving grace of the film’s occasionally televisual feel. The location photography is stunning – Shane looks absolutely gorgeous in 4K – with the Wyoming landscapes and the mountains near Jackson Hole, where the Starrett homestead and nearby town sets are located, gloriously framed against the epic, wide-open American West. When the film moves onto soundstages, the artifice becomes more apparent, but Stevens’ direction remains solid in these sequences, and elements like costuming, set design and lighting are all strong, even if they never quite feel dirty enough. You know that crisp, antiseptic lighting so common to films of the 1950s and 1960s, where there’s never a hair out of place or a genuinely unfortunate streak of mud on anyone’s costume despite living in the muck? Yeah, Shane has plenty of that. The film carries a restrained fantasy in its depiction of the Old West, and if you can suspend your disbelief just a little, it remains a worthwhile experience.

And then there’s that ending. After the violent showdown in the saloon, Shane – reputedly wounded but never actually shown bleeding – rides off on his horse, with young Joey crying out after him, into the vast wilderness, supposedly to die of his injuries. I rewound this sequence a couple of times and, as far as I can tell, while Shane is clearly not as saddle-ready as he might otherwise be, there’s no definitive indication that he’s riding off to die in the scrub. Joey references the wound, but it’s never made clear whether it’s mortal or merely a graze, and Shane’s demeanour remains deliberately opaque. Those who argue that he’s riding off to die might be correct, but there’s just as strong an argument against it. A heroic martyr’s death certainly feels appropriate within the film’s broader themes of a fading Old West – the settlers representing a more modern United States, no longer beholden to the gunslinger past embodied by Shane himself – and I do appreciate the unresolved nature of the finale. As a kid, Joey’s desperate cries for Shane to return were deeply emotional; as an adult, the moment feels less heroic and more mournful, akin to watching an uncle or cousin leave to live overseas.

So what do I make of Shane today? It’s a film firmly rooted in its 1950s production values, with a directorial style that favours low-key restraint over spectacle, but the underlying story is strong enough – even if it now feels very familiar – to overcome many of its shortcomings. Alan Ladd and Van Heflin, and to a lesser extent Jean Arthur and Emile Meyer, are compelling screen presences, while the glorious location photography and Victor Young’s stirring score firmly anchor the film in its time and place, positioning it as a defining work for director George Stevens. There’s a reason Shane has endured as a cult classic, if not an outright mainstream one, and while it feels clunky and plain in places when viewed through a modern lens, there’s no denying the impact of a simple story told effectively. Definitely a cracker for fans of westerns, and an intriguing forerunner to the Clint Eastwood Man With No Name vengeance cycle that would follow a few decades later.