Movie Review – Man With The Golden Arm, The

Principal Cast : Frank Sinatra, Eleanor Parker, Kim Novak, Arnold Stang, Darren McGavin, Robert Strauss, John Conte, Doro Merande, George E Stone, George Matthews, Leonid Kinskey, Emile Meyer.

Synopsis: A junkie must face his true self to kick his drug addiction.

********

Enormously controversial upon release, Otto Preminger’s 1955 drug addiction-themed Frank Sinatra drama The Man With The Golden Arm is a flat-out masterpiece and one of the most memorable film experiences I’ve ever had. Revelatory for its sensitive, shocking and accurate depiction of addiction, controversial because such a topic was considered taboo in McCarthy-era USA at the time, and notably refused a Hayes Code seal upon release – usually the mark of death for a major release, although the film went on to become successful at the box office – the film is a gem of dramatic fiction dealing with an all too real, all too human problem with accuracy, truth and remarkable strength.

Sinatra plays Frankie “Dealer” Machine, a former junkie just returned from a Federal Narcotic farm to Chicago, where he immediately runs afoul of the very thing that put him away in the first place: drug addiction. He reunites with his crippled wife Zosh (Eleanor Parker – The Sound of Music), who guilts him to stay with her as her carer after the revelation that Frankie caused her paralysation from a drunken car wreck. As a former card dealer for loan shark Schwiefka (Robert Stauss), he is soon lured back into the city’s dark underbelly, along with snakelike drug dealer Louie Fomorowski (Darren McGavin), who continues to tempt Frankie with returning to his addiction. With the help of his nightclub waitress romantic interest Molly (Kim Novak), Frankie must dance with the devil again before seeing the light.

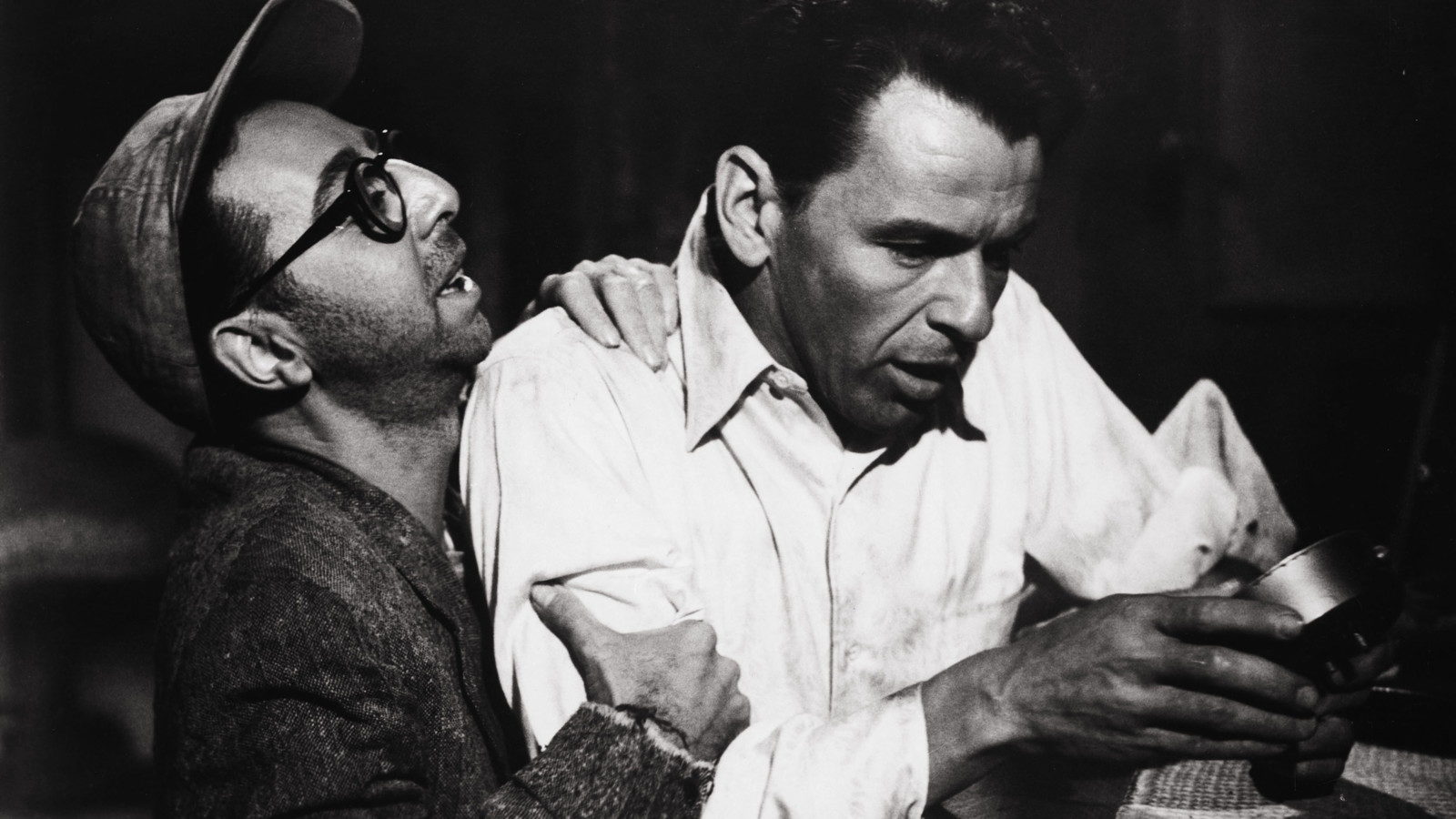

In many ways, The Man With The Golden Arm deals with drug addiction in similar ways to Danny Boyle’s much later Brit-pop film Trainspotting. Director Otto Preminger takes the rank, seedy nature of drug addiction and manifests a sordid tone around how easily people fall prey to its clutches, depicting how it ruins lives, and showcasing how difficult it is to escape. The film pulls absolutely no punches in selling that this is a heroin addiction, despite never mentioning the drug by name, and euphemistically referring to the ingestion as “a fix” to shortcut and bypass censorship. Walter Newman and Lewis Meltzer’s screenplay is beautifully anachronistic of the mid-50’s period in which the film was made, lingo and dialogue as realistic as possible despite the often stylised direction. This is an ugly story told with nuance and grace, a mournful aesthetic blanketing Frankie’s journey from “recently recovered” to “tremulous junkie” in the relatively short span of two hours, and I doubt there’s a more impactful film of its kind from this era. Certainly, a lengthy cold-turkey withdrawal sequence undertaken by a raw and honest Frank Sinatra is superbly done, with Preminger’s tracking-shot camerawork astoundingly in-your-face with brutality at just how insidious addiction can be – and Sinatra, to his credit, never flinches away from the role.

In perhaps his most non-A-list turn ever, Sinatra plays Frankie Machine with a wide-eyed, yet troubled, streak. He aspires to be more, to be better, if only he wasn’t encumbered with a crippled wife he doesn’t love, and a strip-joint hostess who might just be as unfaithful to him as his addition, despite his affection for her. It’s honestly refreshing to see a big name like Sinatra play a role so… dirty, so grimy and salacious, and where you might expect the actor to want to protect his brand or image, here he absolutely goes for broke. He nails the role of Frankie Machine, trying desperately to escape his past, move on with his future, and failing oh-so-humanly at both. This isn’t a morally upright character, not in the least – the dude wants to ditch his invalid wife (well, spoiler, she’s not really an invalid but that doesn’t make his motivations any less pure) for another woman and we’re expected to think this okay? Yet, Sinatra convinces us, alongside a ferocious Eleanor Parker, that this is a decision for the best. Parker, for her share of screen time, is odious as the duplicitous Zosh, a woman banking on guilt to keep her husband in line with the pretence of eternal paralysis, and while her motivations are less clear as the story progresses there’s a symbiotic yin-yang subtext going on here that works for the story.

The supporting cast is excellent, from Kim Novak’s loving yet sad Molly, who yearns for Frankie but can’t be with him because of his habit, through to the bespectacled and earnestly inane Sparrow (Arnold Stang), an old friend of Frankie’s who hustles to get by, and the film’s primary “villain”, the drug supplier Louie. Darren McGavin almost – almost, mind you – makes drugs acceptable with his charm and gentle goading, knowing which buttons of Frankie’s to push in order to get him to use again. His double-act with fellow screen baddie Robert Strauss, as a conniving gambling hustler, Schwiefka, who himself looks very much like a Mafia Don, is the pivot upon which most of the film’s tragic outcomes hinge, and both actors are excellent. Emile Meyer plays the irascible Chicago police chief Bednar, while Doro Merande has a minor supporting role as Vi, a neighbour who has been caring for Zosh while Frankie was “away”.

The film would be nothing if not for Otto Preminger’s daring, exhaustive direction. His camerawork is virtuosic, from protracted tracking shots, Dutch angles, whip pans and terrific crash-zooms, the film’s dynamism and energy crackles through the screen. Cinematographer Sam Leavitt’s brilliant use of monochrome film stock, coupled with stylish lighting design against the dreary (on purpose) set design turn this potential wrist-slitter into something approaching a visual opera. Coupled with Elmer Bernstein’s sublime jazz-infused score, something I’d not thought to consider back when I first watched this, The Man With The Golden Arm is a piece of technical wizardry. At times you can see parts of the sets being moved aside as the camera pushes through; keep in mind, film cameras of the 1950’s were enormously bulky things, and moving them on any kind of dolly track or crane arm was both technically complex and spaciously considerable, but the end result adds a real showmanship quality to the production that engenders realism within the fiction. The film’s production is entirely on a stage, including the exterior scenes, and this sense of constructed reality only adds to the deception drug addicts inflict upon both themselves and their loved ones. Artificiality is the order of the day, until the sunlight bleaches the cockroaches away…

Back in the mid-2000’s, a dirty DVD copy of The Man With The Golden Arm changed the way I thought about “old Hollywood”; depending on your source the film is showing its age on a technical level, but at an artistic one this one could be hung in the Louvre. Preminger, who also directed the incendiary rape film Anatomy of A Murder with Jimmy Stewart, understands humanity and, perhaps even moreso, understands how humans fail, and seeks to represent this rather than hide it away like some dirty secret. It’s a powerful representation of the drug industry, of addiction, and of duplicity, and I cannot recommend it highly enough. A fascinating glimpse into America’s stalled understanding of drugs in the deep shadows of World War II, a rise in crime and how insidious this disease can be, The Man With The Golden Arm is a flat-out miracle of a movie and I find so much to appreciate within it every time.