Movie Review – Rapa Nui

Principal Cast : Jason Scott Lee, Esai Morales, Sandrine Holt, Eru Potaka-Dewes, Gordon Hatfield, Anzac Wallace, George Henare, Rena Owen, Pete Smith, Rawiri Paratene, Cliff Curtis, Lawrence Makoare, Hori Ahipene, Nathaniel Lees.

Synopsis: Love between the representatives of two warring tribes changes the balance of power on the whole remote island.

********

Ill-fated Romeo & Juliet themes abound in this Kevin Reynolds period epic that’s nowhere near as bad as the critics made out to be, but definitely isn’t very good, either. History be damned, Reynolds and his co-writer Tim Rose Price compress hundreds of years of Polynesian Island Rapa Nui’s empire fall into a relatively brief interlude about deforestation and overpopulation, as two distinct classes of the island’s inhabitants war over the rapidly diminishing supplies of food and try to complete the ruler’s questionably disproportionate distribution of manpower to building the nation’s iconic maoi, enormous statues that now dot the isolated landscape. In what becomes a fairly benign spot-the-titty competition amidst a valiant effort to replicate an ancient society’s great downfall, Rapa Nui is cumbersomely written although handsomely mounted by the master of the 90’s spectacle epic – led by Jason Scott Lee and a vastly underrated Esai Morales (Mission Impossible: Dead Reckoning), the film’s grand tone and truly spectacular landscapes form a competent yet empty blast of cheesy simplified human failures and sweeping romantic masculinity, with poor Sandrine Holt stuck in the middle.

The film unfolds in the 17th century, at a time when the inhabitants of Rapa Nui, aka Easter Island, believes themselves to be the only humans on Earth thanks to their isolation and the absence of evidence proving otherwise. Long Eared tribesman Noro (Jason Scott Lee) and Short Ear Make (Esai Morales), both warriors from the main rival clans on Easter Island seek the approval of their society whilst recognising they are always to remain enemies thanks to being born to different tribes. While the island’s ruler, Long Ear leader Ariki-mau (Eru Potaka-Dewes) tasks the subservient Short Ear tribe to construct massive stone effigies, or moai, to curry favour with the gods, using up the rapidly diminishing natural resources, the islanders also prepare for the annual Birdman Competition, a ritualistic contest that determines the leadership of the island for the upcoming year. Noro, fuelled by ambition and a desire to unite the island, finds himself caught in a love triangle with the beautiful Ramana (Sandrine Holt). Ramana, torn between the two warriors, becomes a symbol of the cultural and personal conflicts that underpin the narrative.

Kevin Reynolds knows how to put on a show. Following the blockbuster success with Robin Hood: Prince Of Thieves, Reynolds and producing partner Kevin Costner would sink $20m of Warner Bros money into what would become one of 1994’s biggest financial flops, although you get the sense that there as a road paved with good intentions somewhere in the background to all of this. Rapa Nui isn’t a bad film, and it’s not exactly dishonest with the overall endeavour it undertakes to bring a little-known ancient culture to the big screen, so props for Reynolds for swinging his dick at the studio to get them to sink money into the project. It was, however, a misguided enterprise, with the film gathering a paltry $305,000 in global receipts before it… well, sank without a trace. I’m here to declare Rapa Nui unworthy of such ignominy, although the calamitous ROI isn’t entirely unearned due largely to a paper-thin plot, uneven characters and a hinderance of emotional connection. Between this film and Ridley Scott’s equally maligned 1492: Conquest of Paradise, audiences showed through their wallets that there was simply no appetite for historical epics of this nature in the 1990’s.

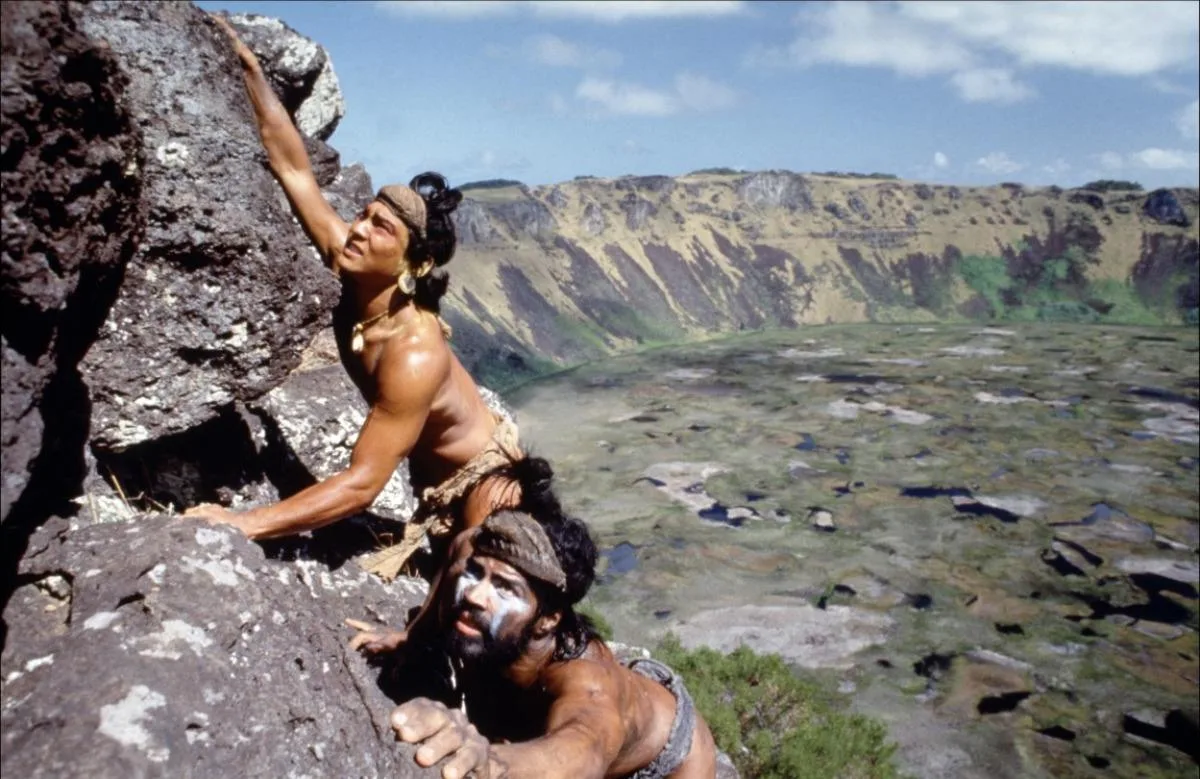

The plot isn’t exactly thematically creative, either. Two dudes lusting after the same gorgeous beauty, all the while having to contend with the fact that they belong to different tribes, meaning at least one of them is an “other” and reviled as such. Throw in a culture of violence and depravity – and a distinct lack of modernity – and you have a backdrop for a divertingly benign love story wrapped with jealousy, impending conflict and giant fucking statues. Legendary for its archaeological maoi, Easter Island’s claim to fame, the film seeks to depict how these enormous monoliths were carved from the rock escarpments around the coastline, hauled across the tundra and into position overlooking the surrounding ocean, and as much as I can decry the film for skewering historical accuracy, this aspect to it is really quite well orchestrated. Heck, even the Birdman cult, from which this film takes great liberties in representation, was a real subsect of the island’s society at one point, so you can’t really fault the filmmakers for at least trying to bring accuracy to what transpires on-screen, even if all the buff, clean-shaven hunks dotting the frame might feel a touch supermodel-catalogue casting. I applaud Reynolds and his team for at least trying to give us an authentic experience with a Polynesian culture, even if it’s botched by shallow writing and a comedic streak that turns the film’s primary antagonist into a clownish trope that undermines much of the premise’s serious undertones.

Crucial to the film’s success is the casting, and I think the acquisition of both Jason Scott Lee and Esai Morales are net positives for the movie. They make solid, if underwritten, dual leads, as the men competing for the hand (or rather, vagina) of young Ramana. For her part, poor Sandrine Holt is grossly underutilised as the romantic interest, a tokenistic role that serves little purpose than be titillating and beautiful enough to compel out heroes on their respective paths to inevitable conflict. Holt is gorgeous enough, but I spent more time staring at her breasts than I did understanding her character – she’s a vacant sex symbol for the boys, as depressing as that might seem, but absolutely designed for the 90’s as a glamorous leading lady. To be honest, there was so much nudity in Rapa Nui that it actually became distracting. Don’t get me wrong, I’m all for historical accuracy as much as the next person, but there were so many naked people cavorting, dancing and standing in the scenery you couldn’t help but be caught off guard by just how rampant the nudity really was. A sequence in which a naked Sandrine Holt’s character is attacked in a reed-filled water pool by a gaggle of equally nude female islanders might seem gratuitous, with its unsubtle water-play subtext, because it doesn’t really move the characters forward, and…. hell, who am I kidding, it was gratuity, plain and simple. Boobs, bums and babes everywhere, and while my 90’s-era film fan self would have undoubtedly declared Rapa Nui to be the visual treat film of the year, the more mature version of yours truly watched on in amazement as Reynolds took every opportunity to flood the frames of his film with on-point cultural representation at the expect of my concentration on the story. Instead – boobs.

From a production standpoint, everything about Rapa Nui screams “big budget” filmmaking, and coupled with The Police drummer Stewart Copeland’s sweeping, downbeat score there always feels like there’s an expectation throughout the film that you should Be Impressed. But spending a lot of money in a far-flung shooting location doesn’t ensure cinematic success, and while the windswept vistas of the real Easter Island look absolutely stunning on a big screen, the emptiness of the story and thinness of the characters make for a truly rugged viewing experience. Rapa Nui is nowhere near the filmmaking disaster contemporary reviews might have made it out to be, and as a film experience it’s assuredly one of the more visually dynamic – and hell, just for representing Pacific Island culture so enthusiastically, if egregiously, I’ll give it a couple bonus points – but there’s a deficit in emotional connection here that no amount of “sweeping epic” camerawork can overcome.