Movie Review – Heat

Principal Cast : Al Pacino, Robert DeNiro, Val Kilmer, Jon Voight, Tom Sizemore, Diane Verona, Amy Brenneman, Ashley Judd, Mykelti Williamson, Wed Studi, Ted Levine, Dennis Haysbert, William Fichtner, Natalie Portman, Tom Noonan, Kevin Gage, Hank Azaria, Danny Trejo, Susan Traylor, Kim Staunton, Henry Rollins, Jerry Trimble, Tone Loc, Ricky Harris, Rak Buktenica, Jeremy Piven, Xander Berkeley, Bud Cort, Dan Martin, Steve Ford, Hazelle Goodman, Paul Herman, Farrah Forke, Niki Haris, Yvonne Zima.

Synopsis: A group of high-end professional thieves start to feel the heat from the LAPD when they unknowingly leave a clue at their latest heist.

********

Few cinema fans today would argue that Michael Mann’s Heat, starring a knockout ensemble rivalling the Harry Potter franchise or Wes Anderson films, is one of the director’s best films. From 1992’s The Last of the Mohicans to 2004’s Collateral he had an unbroken run of critically successful films, and despite most of them not hitting commercial success have come to be regarded as classics in their own specific genres. Heat, a crime-action-thriller starring Al Pacino and Robert DeNiro in what was their first on-screen pairing after iconic careers in separate films, was a remake of Mann’s own 1989 television serial LA Takedown (which, incidentally, featured Xander Berkeley, who makes a minor cameo in this film, perhaps as a tip of the hat) and features Mann again on screenwriting duties. Evoking a dank, depressing take on Los Angeles and its seedy underbelly, Pacino’s detective Hanna and DeNiro’s pro thief Neil McCauley find themselves in each other’s crosshairs as their career paths bring them into a collision of violence and betrayal.

DeNiro was in the midst of a stellar decade of successes at the time Heat came along. 1990 saw his Oscar-nominated turn in Goodfellas, a 1991 remake of Cape Fear (wth Nick Nolte) as well as Backdraft, a remake of Frankenstein in which he played the Doctor’s infamous monster, Scorsese’s Casino (now regarded as a masterpiece), Tarantino’s Jackie Brown, Frankenheimer’s Ronin, and the smash-hit comedy Analyse This. Heat is arguably the most prominent of all those films mentioned (with the exception of Goodfellas) due largely to the incendiary cast, a white-hot script and the scintillating performances, although the uncomfortable on-screen pairing between he and romantic interest Amy Brenneman, some twenty years his junior, remains a singularly jarring off-note.

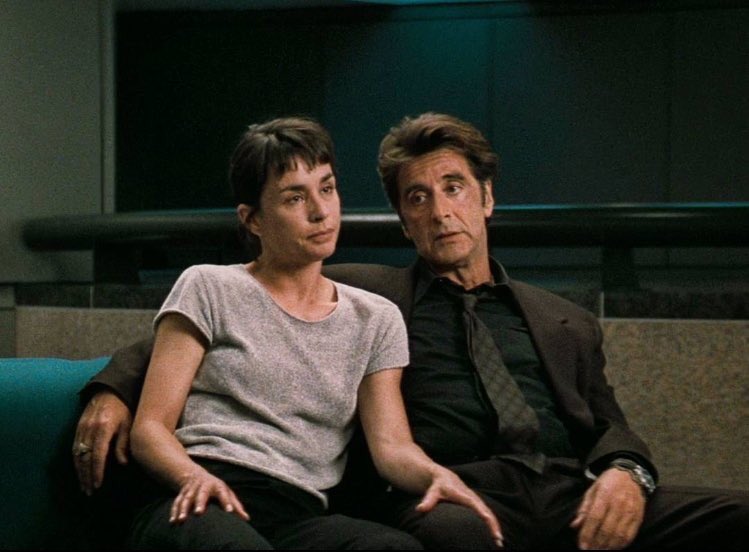

For comparison, Al Pacino was also in the midst of a career best decade in the 90’s, following a Best Picture Oscar tilt for The Godfather Part 3, a Best Actor win for Scent of A Woman, and critically acclaimed turns in Carlito’s Way, City Hall, Donnie Brasco, as well as his eminently meme-worthy work in both The Devil’s Advocate and Any Given Sunday. While Heat gives Pacino a chance to play a more low-key character than he is typically afforded, his famous “hoo-haa” style does pop in a few times and gave me a chuckle in re-watching this film. The iconic scene putting both Pacino and DeNiro in a scene together, in a dingy LA restaurant as they indicate their mutual unwillingness to stand aside, has to be one of the great dialogue sequences in film history, and their chemistry together is palpable.

Mann populates Heat with a legitimate “all star” cast, from an at-the-peak-of-his-powers Val Kilmer, the late Tom Siemore, a creepy Jon Voight, bit players Wes Studi, Ted Levine and Mykelti Williamson, a young Natalie Portman, grizzled Danny Trejo and blank-slate Henry Rollins, as well as a snakey, slimy William Fichtner, and cameos from the likes of Hank Azaria, Jeremy Piven and the aforementioned Xander Berkeley. Inexplicably, Mann even gives us the astounding sight of “Funky Cole Medina” singer Tone Loc acting in a scene opposite Robert DeNiro, which I would imagine is one of the more bizarre directorial choices Mann has ever made; I would also imagine DeNiro had no idea who he was acting with until well after the fact, and that makes me laugh. Strong female roles to Diane Venora, as Hanna’s put-upon long time girlfriend, Brenneman as DeNiro’s infatuation, and Ashley Judd as Val Kilmer’s on-screen love interest, add balance to what is pretty much a sausage-fest most of the time, with the balance being between work-life and play for the central characters, despite a constant feeling of being underwritten only as contrast for the hyperbolic masculinity everywhere else.

Where I think Heat really works the strongest is its editing. This is a superbly edited film, and running at nearly three hours (depending on whether you watch the original theatrical or more recent directors “definitive” cuts) you’d be forgiven for expecting some parts of the movie to feel a little slower – you’d be wrong, however. Heat moves like a freight train, with every second of the movie counting in terms of propelling either the narrative or character arcs forward. Mann balances the DeNiro plot and the Pacino plot like a conductor, expertly weaving between both as it suits the story, and maintaining a propulsive tone that explodes upon the viewer with the film’s climactic street shootout in downtown LA. And yet this moment arrives about midway through the film, with a number of resolutions and character beats to come still maintaining interest thanks to tense, almost unbearable sense of fatalism permeating the movie. Will the bad guys get away with it? Will the police catch them? Who, and how many, will die in the meantime?

Mann never embellishes his film, content to just let the characters tell the story and oftentimes Heat feels very much a verité production with its fly-on-the-wall style cinematography and pulsating, score-free action. Indeed, the film’s bravura shootout sequence is a wall-shaking frenzy of gunfire and reverberations mixed with clattering glass, bodies and violence, yet at no stage does it resemble action films of the period (looking at you, Michael Bay and Dominic Sena), with a washed out colour palette and real graininess to the footage. The fact that there’s a cleanliness to the edit, going against the action film grain in many ways, is indicative of Mann’s grasp of using violence to punctuate the quiet around it. There’s no pornographisation of the violence other than that its intent is to horrify the viewer – and it often does – which gives Heat its torn-from-the-headlines feel of realism.

Look, I’m an unabashed admirer of Michael Mann and his style of filmmaking, despite it not always working for me (Black Hat), and I think Heat is easily his best overall work. Captivating writing and performances, stylish camerawork and sheer star-power ensure Heat remains the absolute classic it has become regarded as, and always will be. Pure filmmaking dynamite.