Movie Review – Godfather Part II, The

Principal Cast : Al Pacino, Robert Duvall, Diane Keaton, Robert DeNiro, Oreste Baldini, John Cazale, Talia Shire, Lee Strasberg, Michael V Gazzo, GD Spradlin, Richard Bright, Gastone Moschin, Tom Rosqui, Bruno Kirby, Frank Sivero, Morgana King, Francesca De Sapio, Mariana Hill, Leopoldo Trieste, Dominic Chianese, Amerigo Tot, Troy Donahue, Joe Spinell, Abe Vigoda, John Aprea, Harry Dean Stanton, Danny Aiello, Roger Corman, Peter Donat, William Bowers, James Caan.

Synopsis: The early life and career of Vito Corleone in 1920s New York City is portrayed, while his son, Michael, expands and tightens his grip on the family crime syndicate.

********

It may surprise you to learn that Francis Ford Coppola’s 1974 sequel to his Best Picture-winning masterpiece, The Godfather, was a divisive, polarising film upon its initial release in December of that year. A film even more sprawling in scope than its predecessor, The Godfather Part II was criticised for uneven pace, using a multitude of flashbacks to give us the formative years of a young Vito Corleone arriving in America mixed with the “modern day” Michael Corleone – with Al Pacino reprising the role in his Oscar nominated turn – which many described as “softening” the frisson of the ongoing story at the expense of a mishandled, yet entirely wonderful, prologue sequence that feels inconsequential. In more recent times, the wonder and majesty of the Godfather sequel, a film elongated to over three hours, has seen a reappraisal of the film as easily one of the best sequels ever made, and with its Best Picture winning form at the Oscars, cemented both it and its former film as the most lauded franchise in Hollywood history.

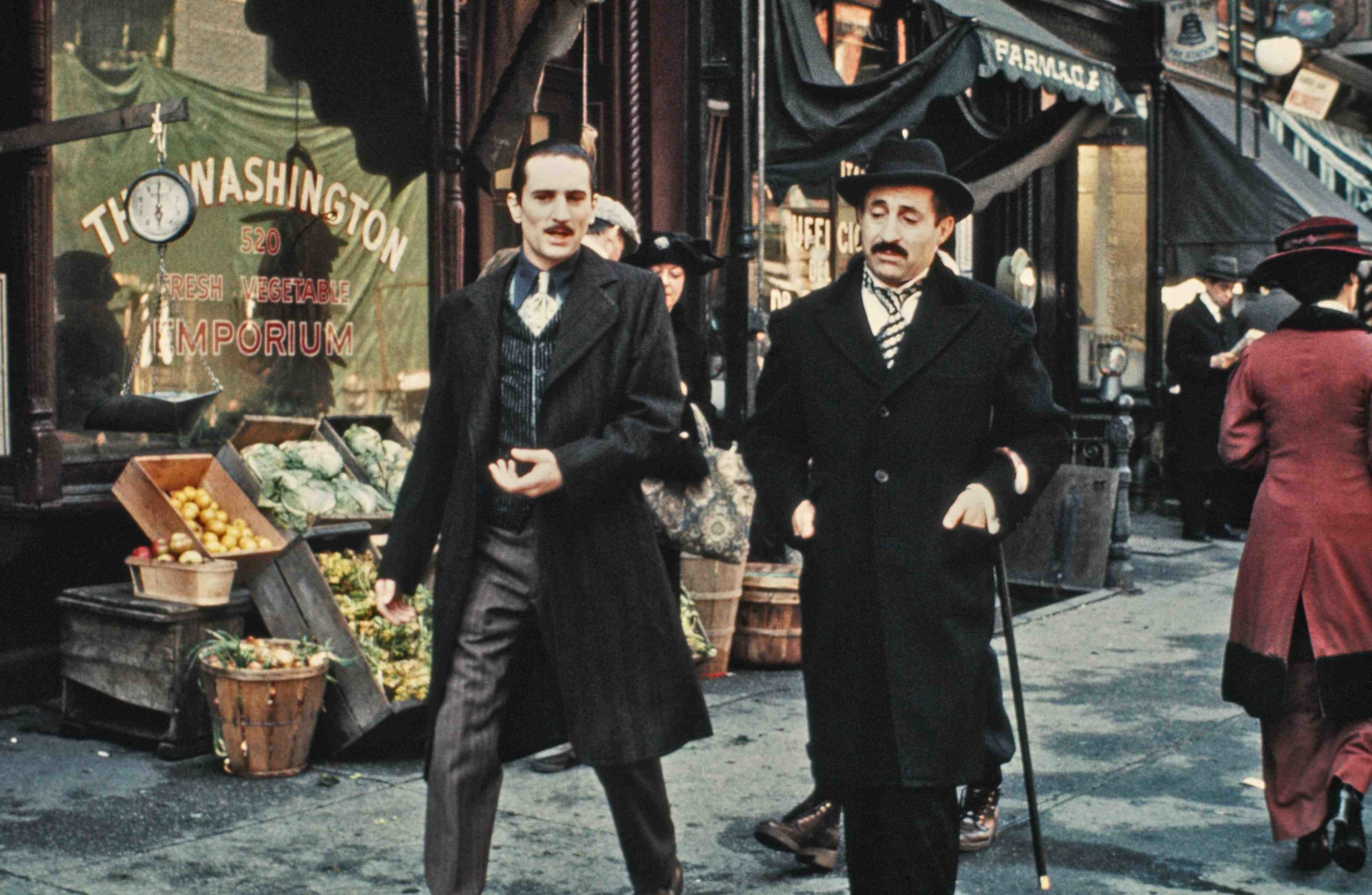

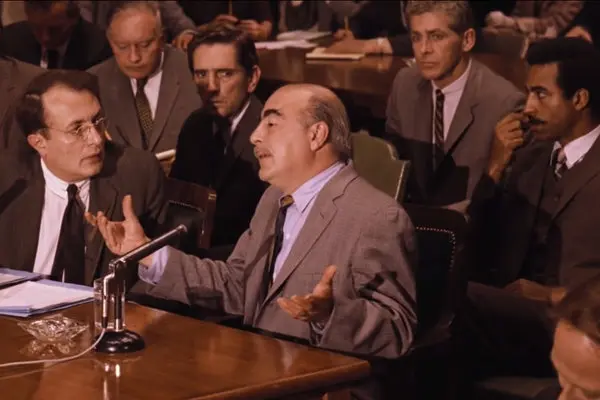

The Godfather Part II is split into two distinct narratives. The first, and by far the most prominent, is set in the late 1950’s and sees Michael Corleone (Pacino) now running the Corleone Crime Family from his Lake Tahoe estate; on the day of his son Anthony’s First Communion, Michael and his wife Kay (Diane Keaton) are nearly assassinated in a hail of bullets, leading to Michael’s dedicated hunt for the names of those who betrayed him. Michael’s business relationship with Florida-based gangster Hyman Roth (Lee Strasberg) is problematic for those around him, particularly his brother Fredo (John Cazale) and family consigliere Tom Hagen (Robert Duvall), while estranged family capo Frank Pantangeli (Michael V Gazzo) turns squealer in an ongoing US Senate inquiry into the Corleone crime syndicate. The second narrative sees a young Vito Corleone (Oreste Baldini as a child, Robert DeNiro as a young man) arriving in America from Sicily in 1901 after he is run off by a sadistic crime boss who brutally murders his mother. The young Vito works the streets of New York City, putting his contacts and intellect to good use setting himself up as a local “Godfather”, for whom many Italian immigrants turn to for help. He is ruthlessly berated by Don Fanucci (Gastone Moschin), the local crime boss of the lower East Side, and is befriended by a young Clemenza (Bruno Kirby) who helps him set up a successful criminal enterprise.

Retrospectively, there is some truth to the notion that Coppola’s sequel is an unevenly paced, occasionally ill-focused affair. From a storytelling standpoint, the balance between the two storylines never quite feels as formidable as its reputation might indicate, with the Vito storyline almost supplanted by the far more dramatic, turgid antics of Michael and his immediate family. The franchise’s brutal violence is evident from the first few scenes – a young Vito Corleone watches in horror as his mother is blown in half by the shotgun of a ruthless Sicilian mobster, setting the stage instantly for a return to the Mario Puzo playbook of wanton death and destruction wherever the mafia existed. Cutting across to the 50s-set Michael Corleone and his family, celebrating his son’s communion, is an echo of the first film’s wedding opening scenes, although here things are laced with undertones of more sinister effect, which a crooked US Senator (GD Spradlin) upbraiding Michael in his office over plans to acquire more Las Vegas casinos, in contravention of Nevada’s gambling laws. Sporadically interspersed with this narrative, DeNiro’s Vito parallels the gradual rise of the young Italian as a powerful force in his new York City neighbourhood, eventually setting the scene for the events of the first film. It should be noted that Marlon Brando declined to appear in a small flashback sequence following a dispute with Paramount (unlike James Caan, who did return for a single scene and was paid the same amount as he was for the entire previous film, what a boss move!), but the way in which Coppola so easily writes around his absence, and magnifies DeNiro’s role as the younger version of the character, is excellent.

Again written by Coppola and Puzo (and again winning Oscars for Adapted Screenplay) from Puzo’s original novel, The Godfather Part II spends a lot of time dealing with Michael’s gradual loss of control over his own family, even when his business interests succeed enormously. Pacino towers over the film, a hypnotic, explosive presence of bottled rage and hurt loyalty – he bleeds for his family and he’ll walk over anyone and everything to keep them together. Even when Kay decides to leave him, shattering his idyllic nuclear-family ideal, Michael’s ruthlessness in life rises again to the fore and, for the audience at least, ruminates on his tragic loss of humanity at the expense of wealth and power. There’s no hiding it this time: Michael is a ruthless asshole here, stomping everyone around him into the ground to achieve his aims, and it’s the film’s depiction of this absence of empathy or a moral centre that is so exponentially frightening. A man with everything to lose is a dangerous man indeed. The dialogue is a promulgation of the earlier film’s instantly popularised Mob-speak, jingoistic and apocryphal in nature to the real-world behaviour and language of the time; there’s allusions to sleeping with fishes, DeNiro gets to utter the iconic “make him an offer he can’t refuse” line herein, with a lot of subtitled Italian from the entire cast: Coppola’s writing for the screen is masterful indeed. Pacino says so much with a look – hell, they all do – that often words aren’t needed. A flash of anger, a glimmer of hatred, the haunting moment Michael kisses Fredo at a party to indicate he knows it was he who betrayed their family, and nothing need be said.

Of the two distinct narratives, I honestly prefer the one involving DeNiro’s Vito Corleone. Getting to see how the figure of Brando was formed prior to the events of the first film is a fascinating, scintillating method of engaging the viewer. The all-too-brief interludes into the past here are superbly filmed, exquisitely acted by DeNiro, Gastone Moschin, Frank Sivero (as a harangued landlord encountered by Vito late in the movie), and a young Bruno Kirby (also known to rom/com lovers as Jess from When Harry Met Sally), and have a sense of pace and timing and flavour that few films – save perhaps Sergio Leone’s Once Upon A Time In America – have ever truly captured. The early 19th Century New York City production design is flawless, as is Coppola’s use of lenses, colour, and flashes of violence to envelop the viewer. It should be noted that DeNiro snagged an Oscar for Best Supporting Actor for his work here, one of three nominations the category alongside Michael V Gazzo and Lee Strasberg, although I hesitate to suggest that perhaps it isn’t a role notable for its Capital-A Acting requirement. Pacino, who was nominated but didn’t win in the Best Actor category, deserved to win in my opinion.

The film’s strongest dramatic element, however, is the Pacino-led Michael Corleone storyline. It has a plethora of returning faces, including Talia Shire as Connie Corleone, Morgana King as the Corleone matriarch Mama Carmela, Abe Vigoda as Salvatore Tessio, and John Cazale as Fredo, alongside central figures like Robert Duvall and Diane Keaton in their respective reprisals. Lee Strasberg makes for a slimy character in the film’s violent Cuban-set mob scenes, as the wonderfully named Hyman Roth (seriously, who would name their kid Hyman?), while Michael V Gazzo’s turn as Frank Pentangeli is one supporting role for the ages. Pacino’s work against the film’s demanding dramatic arcs is sublime, and he pulverises ever scene he’s in with trademark venom and vigour. Michael Corleone is a hell of a meaty character and Pacino absolutely goes for broke, alternating between a shattered family man and a ruthless criminal with a lust for power and wealth, making him a dichotomy of the American ideal and a formidable fictional figure in cinema. While I felt the subplot involving Roth wasn’t particularly strong enough to warrant such lengthy exposition, the arc around Frank Pantangeli’s stool-pigeon turn to the FBI was one hell of a dynamic plot twist that I didn’t see coming. The betrayal by John Cazale’s Fredo, a crucial and defining moment for the franchise, remains a signature sequence and iconic moment for the entirety of Hollywood’s storied history, with both Pacino and Cazale (who would be dead just four years later from lung cancer) delivering powerhouse performances in these key scenes.

In terms of technical production, The Godfather Part II is a very strong movie indeed. Gordon Willis’ sumptuous cinematography continues the aesthetic commenced in the first film, facilitating bright and sunny Sicilian landscapes against dour, brooding old New York ones, while locations in and around Miami, Lake Tahoe, and a protracted sequence in Cuba, are all complex in their execution. Italian-born composer Nino Rota, also returning for the sequel, delivers more of his popular mandolin-infused themes amid a layered, nuanced orchestral score: the music of The Godfather films, particularly the two in which Rota was involved, have musical accompaniment that seems to sit in the background and just murmur away, refusing to spotlight itself when it is designed as an appetiser for the visuals on screen.

It’s the editing that takes center stage – a total of three pairs of hands are credited in this department, Peter Zinner, Barry Malkin and Richard Marks, with Zinner being the only one from the previous film returning – and it’s at this point the film really hits its stride. Editorially, each sequence individually absolutely sings, from camera angles, pacing and structure, to the grandiose sound mix accompanying the film. ADR tends to be a bit of a bother though, with more than a few moments of lip-sync being problematic and dragging the viewer out of the film. Still, structurally and storytelling-wise, The Godfather Part II is a monumental achievement in editing: the complaints against the dipping between the past and the present throughout do make for cumbersome pacing here and there, the film’s intimidating structure and a variety of cliffhanger plot points inadequately spliced together to create a cohesive whole a times. In all honesty, I’d have preferred it had Coppola simply presented each storyline as a whole linear sequence individually, maybe giving us an intermission between historical landmarks to separate the two, because I think that might have afforded the DeNiro segments to settle with the audience a little sweeter before getting to the Pacino stuff with a full head of steam. In any case, it makes for a fascinating case-study in editorial choices, and a remarkable, if not entirely successful, foray in intercutting competing narratives to maintain viewer interest.

The Godfather Part II is indeed worthy of the plaudits and reputation it has gathered since it released back in 1974. Time has been eminently kind to this formidable cinematic masterpiece. It isn’t without flaw, but these minor quibbles are easily overlooked when you consider the sheer weight of talent both in front of, and behind the camera. Coppola was at the height of his powers here, delivering yet another full-throated dramatic thundercrack across screens that remains an indelible, iconic moment of cinematic virtuosity. With a blue ribbon cast firing on all cylinders, superb production design (another of its well-deserved Oscar nominations went to Costume Design) and a roster of characters as engaging and brutally humanistic as anything you’d see in real life, The Godfather Part II is easily one of the great films – sequel or otherwise – and accompanies its predecessor as a legitimate masterpiece.