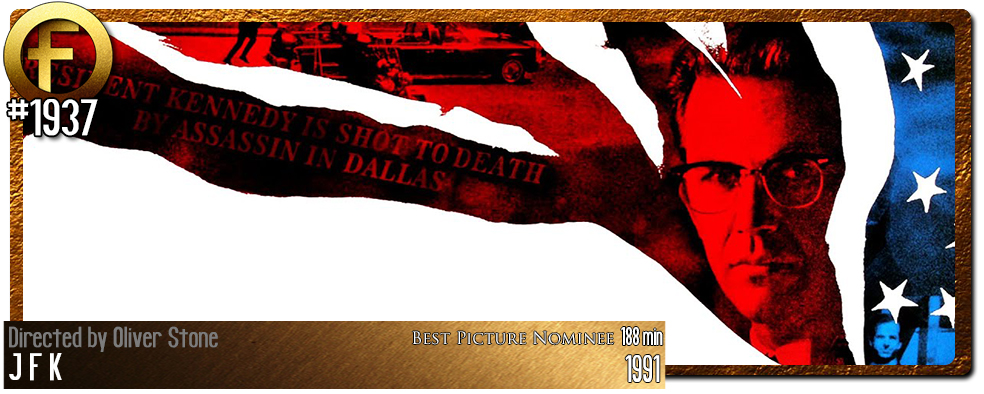

Movie Review – JFK

Principal Cast : Kevin Costner, Tommy Lee Jones, Laurie Metcalf, Gary Oldman, Michael Rooker, Jay O Sanders, Sissy Spacek, Kevin Bacon, Joe Pesci, Jack Lemmon, Walter Matthau, Donald Sutherland, Ed Asner, Beata Pozniak, Brian Doyle-Murray, John Candy, Sally Kirkland, Wayne Knight, Pruitt Taylor Vince, Tony Plana, Vincent D’Onofrio, Dale Dye, Lolita Davidovich, Ellen McElduff, John Larroquette, Willem Oltmans, Tomas Milian, Gary Grubbs, Ron Rifkin, Peter Maloney, John Finnegan, Wayne Tippit, Jo Anderson, Bob Gunton, Frank Whaley, Jim Garrison.

Synopsis: New Orleans District Attorney Jim Garrison discovers there’s more to the Kennedy assassination than the official story.

********

Of significant events to occur in the 20th Century, ones in which people “remember where they were when…”, easily slotting into the top five of every list would be the assassination of US President John F Kennedy. The popular president, still the youngest person to assume the the role, was killed by an assassin’s bullet on November 22nd, 1963, during a motorcade procession through the Texan city of Dallas. Upon his death, then-Vice President Lyndon Johnson assumed the role, captured in a famous photograph aboard Air Force One standing next to former First Lady Jackie Kennedy, who was still covered in her husband’s blood. At the time, media hysteria laid blame on a lone assassin, Lee Harvey Oswald, who proclaimed his innocence until two days later, when the accused killer was himself slain by Jack Ruby in the basement of the Dallas police headquarters. Ever since, the legend of JFK and the assassination has only grown through the decades, with theories of conspiracies over whether Oswald pulled the trigger, or whether the President was killed by other, nefarious faceless men who have never seen trial over the affair. Oliver Stone’s polarising feature attempts to rip open the weeping scab of one of America’s darkest days in his usual inimitable style, boasting a stellar cast, demanding narrative whiplash and a frantic editorial style make for compelling vérité cinema; whether you subscribe to Stone’s hysteria over the famous event or not, or agree with his statements as fact or heavily fictionalised, there’s no denying the emotive storyline packs a certain wallop that remains undiminished over time.

New Orleans District Attorney Jim Garrison (Kevin Costner) is as shocked as any American to learn that President Kennedy has been shot and killed in Dallas, Texas, on a sunny November day in 1963. He and his investigative team learn that the assassination has links in his own city, specifically a plot by resident David Ferrie (Joe Pesci), and set about beginning an investigation, before the accused assassin, Lee Harvey Oswald (Gary Oldman), is shot and killed only a few days later. Years later, Garrison is astonished reading the Warren Commission’s report into the assassination, believing there to be several glaring inconstancies and problematic detective results leading him to reopen the case. Through a series of interviews with witnesses to the event, as well as named people linked to various conspiracies, Garrison ends up arresting and sending to trial notable New Orleans businessman Clay Bertrand (Tommy Lee Jones), who had links to both David Ferrie and Oswald through various political affiliations in his city. Through the trial, Garrison unpacks his version of events leading up to, and following the assassination, including pointed arguments that Oswald could never have carried out the attack alone, and that people within the US government itself might very well be implicated.

Anyone doing even the smallest amount of research into the Kennedy assassination could only ever come to the conclusion that Lee Harvey Oswald could not have possibly have carried out such an attack on his own. That’s not JFK’s big reveal, really. Instead, what does become a jaw-dropping hook for Stone’s garrulous narrative is who the other party (or parties) may have been. Stone casts a wide net in his search for the truth as he sees it, aiming his laser-like focus on various conspiratorial possibilities, painting Oswald as a hapless patsy in one of history’s most iconic, indelible moments. Stone, a co-writer on the screenplay with Zachary Sklar, based not only on the real Jim Garrison’s memoir “On The Trail Of The Assassins” but also Jim Marrs’ “Crossfire: The Plot That Killed Kennedy”, gives his film a momentum that can only be described as that akin to a freight-train; the film kicks off with a barrage of newsreel footage from the years preceding the assassination, leading up to a dramatic recreation of the event, before introducing Costner’s Jim Garrison and his office team, including Laurie Metcalf, Wayne Knight and Michael Rooker in key roles, all of whom bring their particular slant to one of the most momentous moments in America’s history.

From there JFK becomes an enormous information dump. Typically these kinds of films don’t work so well if the subject matter isn’t as astounding as JFK’s is, but Stone, together with the Oscar-winning team of editors in Joe Hutshing and Pietro Scalia, maintain our interest and rage at what Stone perceives as a complete miscarriage of justice, and through the crash-bang-wallop of the slick visuals and flashback-within-flashback backstory work you almost can’t disagree with his viewpoint. A viewpoint, it should be pointed out, given the blessing of the real Jim Garrison, who (in one of the film’s grandest moments of sublime irony) appears in cameo moments portraying the very Supreme Court Justice Warren whose report he absolutely repudiates. That the screenplay makes the sensation of info overload seem like a fine wine with dinner mixed with John Williams’ patriotic orchestrations and Costner’s earnest, blue-eyed performance is all the more compelling, with Stone laying the furtive exploratory dissection of Warren’s lengthy (if facetious) dissertation of his findings out for even the dumbest viewer to wrap their heads around it. Understanding the political climate of the 1960’s is also a big help, although not a complete moodkiller, with just enough backdrop setup provided to make it palatable even to people decades distant with the setting.

Whether the film was honed by editorial prowess (my guess) or by Stone’s directorial conductorship is a conversation we don’t have enough of, although the film’s rank pride in the American Dream and how Kennedy’s death was a partial extinguishment of of that dream might seem positively poetic in light of the United States’ current political woes. I’d go so far as to state that JFK is arguably one of the greatest examples of editing for storytelling I’ve ever seen. There’s so much information, so many disparate players to this story, so many hidden corners and rocks to be kicked over, the sheer volume of dialogue, exposition and reconstruction work involved in this movie is astonishing. Shot using a variety of different film stocks, between steadycams, hand-held and traditional cinematography, with a variety of tones and forms between sequential scenes, the effect can be somewhat discombobulating but the overall result is one of potent bullishness towards its subjects.

Costner’s performance as Garrison is typical of his 90’s output, playing the good-guy with a measure of stiff-backed honesty that works just enough without feeling overly sentimental. Costner delivers one of Hollywood’s great monologues with the film’s climactic courtroom sequences in which Garrison goes through the case second-by-second, ending it with a rousing exhortation to the jury (and therefore, us) to stand firm in the face of overwhelming darkness – perhaps Stone is more prescient than we realise, given how far away from the light much of American politics have become since even 1991. The supporting cast around Costner, who holds the film together, is also quite possibly one of the greatest ensembles ever assembled for a single movie. Gary Oldman’s Oswald is an off-kilter, wide-eyed villain of sorts, as is Joe Pesci’s unhinged performance as David Ferrie and the depiction of then underground homosexual proclivities. Tommy Lee Jones’ slimy turn as businessman Clay Bertrand (aka Clay Shaw) is one of the film’s chief highlights, and you just can’t help but want him to get his ass handed to him in the end, while Sissy Spacek is terrific as Garrison’s long-suffering wife. Garrison’s team of Laurie Metcalf, as Susie Cox, Wayne Knight as Numa Bertel, Michael Rooker as Bill Broussard, and Jay O Sanders as Lou Ivon, form a quartet of dedicated ancillary players who assist Stone’s rapid dissertation of explanatory material, with a who’s who of Hollywood star power essaying various smaller roles fleshing out the conspiratorial demagoguery. John Candy, Jack Lemmon, Walther Matthau, Ed Asner, John Larroquette, and Kevin Bacon all have substantive effect on Garrison’s understanding of the plot to kill Kennedy, whilst Donald Sutherland’s mid-film “deep throat” government whistle-blower character is a fascinating example of forming opinions based on information that doesn’t match up – the character also gives one of the film’s best lines: do your own thinking, don’t take my word for it. Which is perhaps the most ironic thing Stone delivers in this powderkeg diatribe against US government corruption.

JFK portrays itself as the definitive answer to the world’s most famous public assassination, when it really isn’t. Oliver Stone, a director noted for his exceptional political bias throughout his film career, delivers a polarising dagger to the heart of rational thinking with this masterclass of editing, a rousing evisceration of the Warren Commission’s work whether true or not. Is it overwrought? Certainly. Is it committed to its concept? Definitely. Is it entertaining? Hell yes, it absolutely achieves that aim. JFK is a masterclass in propagandist narrative storytelling, a heart-on-sleeve belief in a particular outcome whether legitimate or grasping at straws. I think Stone touches on a lot of great points here, working a devil’s dance manipulating the viewer into believing every word (the film has elements of truth but perverts honesty for the sake of salaciousness and an urgency to kick over rocks at every turn), and honestly has one of Costner’s best performances ever (yes, even better than Dances With Wolves) on film. At over three hours, it never once feels like it, maintaining attention with gunshots, whizz-bang editing and a collection of terrific actors doing their thing. But it’s an unmissable film event, one no discerning film fan should skip.