Movie Review – Collateral

Principal Cast : Tom Cruise, Jamie Foxx, Jada Pinkett Smith, Mark Ruffalo, Peter Berg, Brice McGill, Irma P Hall, Barry Shabaka Henley, Klea Scott, Javier Bardem, Emilio Rivera, Thomas Rosales Jr, Inmo Yun, Jason Statham.

Synopsis: A cab driver finds himself the hostage of an engaging contract killer as he makes his rounds from hit to hit during one night in Los Angeles.

********

Nominated for a plethora of industry awards, including Best Supporting Actor for Jamie Foxx and Best Editing at the 2004 Academy Awards, Michael Mann’s crime-noir classic cannot hold a candle to the far superior Heat, and is interesting to me purely as an exercise in technical boundary-pushing. The then-nascent digital camera technology was improving thanks to filmmakers such as George Lucas pushing for its integration into cinematic creation workflows, although the obvious visual differences between early all-digital camera capabilities and tried-and-true 35mm optics was still significant enough to be noticeable – parts of Star Wars: The Phantom Menace were shot digitally, whilst almost all of Attack Of The Clones utilised the new technology in its pipeline – but it would be Michael Mann’s Collateral, shot by cinematographer Dion Beebe primarily on the Thomson Viper Filmstream Camera (a precursor to true 4K cameras used today) that would garner the most praise and controversy for using this method. It helped that the story and characters cemented the film’s popularity among cineastes, with the film’s boilerplate genre archetypes and sense of realistic, brooding menace throughout. If Collateral could be summed up in a single word representative of both story and style, it would be “gritty”.

In the neon-lit streets of a Los Angeles night, taxicab driver Max (Jamie Foxx) picks up US Attorney Federal Prosecutor Annie Farrell (Jada Pinkett Smith) from the airport and drops her at her office. Max’s second passenger is Vincent (Tom Cruise), ostensibly a businessman but it soon becomes apparent that he is a hitman, an assassin, who recruits Max to drive him across town on a variety of missions to kill targets. Although Max is horrified, Vincent continues to coerce the driver to do what needs to be done, until a dogged policeman, Ray Fanning (Mark Ruffalo sporting a terrible late-90’s slick-back hairdo) begins to put pieces of the crime-spree together. The hunt for Max, or rather Vincent, is on.

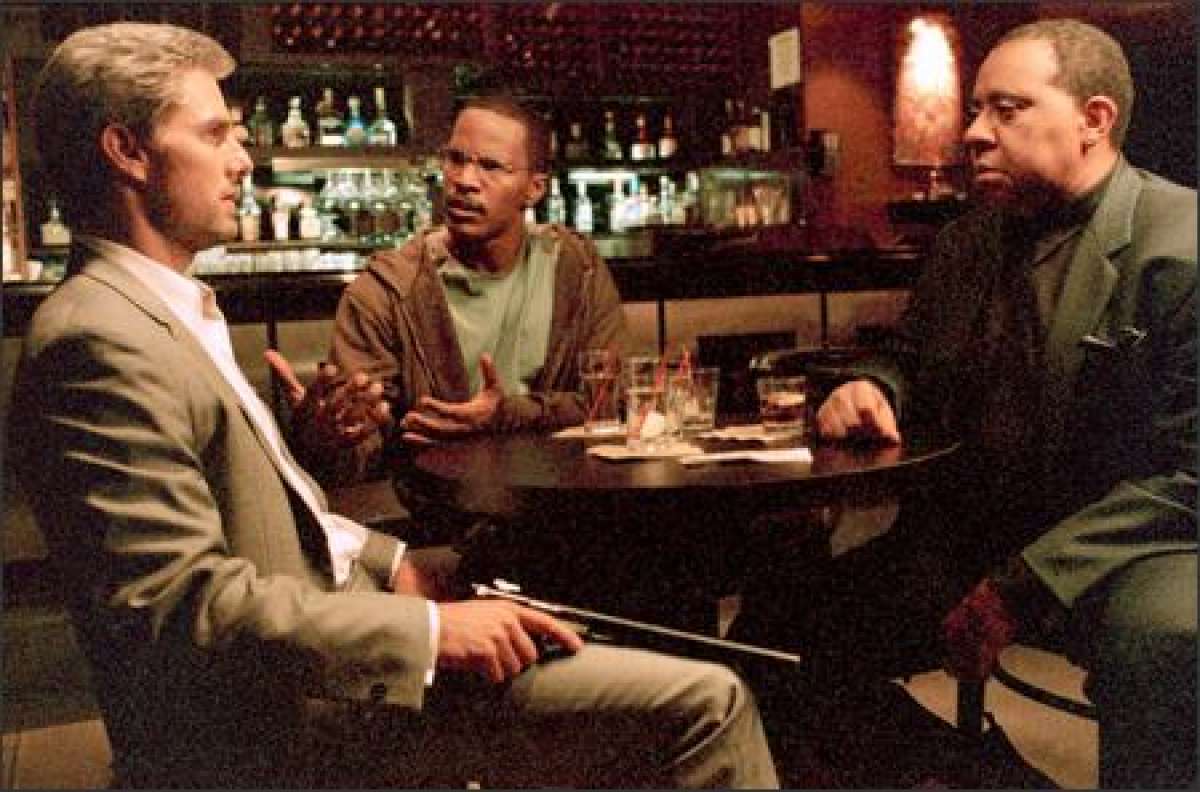

Collateral is a very, very good film. It legitimately borders on great were it not for a contrived, sometimes laughable final act in which convenience trumps logic, but that notwithstanding both Cruise and Foxx are excellent (Cruise is the better, for mine, and yet Foxx got the award chatter… huh) and Mann’s direction of both drama and action are superb. The man can stage an action setpiece like nobody’s business, and although Collateral lacks the powderkeg violence of Heat a decade prior, it makes up for it with some truly pulsating tension and edge-of-your-seat menace. Cruise playing the role of a sinister and dedicated hitman – a reverse of his Ethan Hunt role from Mission: Impossible – makes for a compelling character, with the actor’s renowned point-blank commitment to making the role as violently unhinged as the script will allow yet another reason he’s one of the biggest stars in the world. The decision to give him a blonde hairstyle, accentuated by white-tipped eyebrows and a suitably Miami Vice five-o’clock shadow, ought not to have worked for the actor but it throws us off-balance, and the look of Cruise as a man rigidly adhering to his goal in such a way with such a vibrant, sticks-out-like-a-thumb visual silhouette is actually creepy as hell. Jamie Foxx, in the role of the timid Max, showcases a range of emotional content as the film’s eponymous hero, thrust unwittingly into a horrifying situation and having to make decisions of life and death far beyond his scope of abilities. The contrast between Foxx’s Max and Cruise’s Vincent gives the story its murky noir vibe, the film’s best moments coming not in the abject violence but with calm absurdist philosophy discussion; Collateral works as a character piece moreso than a violent action film, with the balance between the two impeccably measured by Mann and editors Jim Miller and Paul Rubell.

For two-thirds of the film, Mann constructs a razor-sharp pulp crime film (despite an early and incongruous cameo appearance by Jason Statham reprising – of all characters – his role from the Transporter films!) that effortlessly floats through the out-of-focus streets of LA’s night scene. As Max’s taxi grinds the city streets on Vincent’s mission of death, the collision of both men and their unwillling partnership for a common goal forms the basis for most of the movie’s interest and intrigue. Sidebar characters, such as Ruffalo and Peter Berg’s police detective characters picking up after Vincent’s assassinations, Max’s lowkey infatuation with Pinkett Smith’s lawyer role, or Javier Bardem’s sinister and oily gangster archetype (and one of the film’s best scenes) create the sense of a macabre, almost River Styx-esque malevolence at play throughout, personified through a tinge of sickly green or urine-stained yellow lighting design working on a lot of the film’s exterior sequences to great effect. There’s a pulse to the film, a quiet cadence of ubiquitous nonchalant evil pervading Mann’s film, and although LA itself plays a small physical role in the story the backdrop it provides is one of a heaving tsunami of decadence, depravity and urbanity. Vincent’s mission to kill a fistful of people – all interconnected vicariously through Bardem’s character somehow, and the movie’s central MacGuffin – is merely a means to an end for Mann to give us two Hollywood heavyweights giving their all to two indecently different characters, neither without fault, but arguably Max being the most affecting.

Arguably Collateral’s biggest selling point, however, it’s its look. As mentioned, cinematographer Dion Beebe (who replaced original DP Paul Cameron barely weeks into filming) decided to shoot the majority of Collateral digitally, using a very early digital cinema camera to do so; digital photography of that era wasn’t known for accurate renders of black levels, generally resulting in grainy, artefact-ridden footage that lacks the crisp, sharp look cinema audiences expect. Collateral either benefits or suffers from this issue depending on your tolerance for this kind of artistic expression, because it’s a film shot almost entirely at night with minimal “realistic” lighting and, particularly in the film’s climactic final sequence, often in near-pitch black. From what I can gather, the Viper Filmstream Camera used to shoot Collateral was at best capable of capturing footage in 1080p, and for home releases I’ve no doubt the image was upscaled to 4K presentations, resulting in many moments of footage looking like a pretty average home video made using two of Hollywood’s biggest stars. Whether this aesthetic works for you will be a matter of personal taste – I did enjoy it in my recent rewatch, despite loathing it in cinemas initially (I joked to my friends that somebody had dropped the film negative into battery acid before editing it) – and on large 4K television screens the digitally captured footage will stand out starkly against the movie’s more minor 35mm sequences (scenes inside a jazz club and a dance club look positively warm-and-fuzzy compared to the majority of the movie) so be prepared.

What this particularly look does imbue Collateral with, however, is a sense of jarring immediacy, almost redolent of hidden camera trickery or found footage electrification. The visceral nature of Mann’s framing and his use of near constant close-ups on Cruise and Foxx during their in-cab conversations is exemplified by this low-fi look, by design or not, and you can’t help but feel a closer empathy to the characters than a cooler 35mm crispness might mitigate. The differences between Collateral and even Mann’s later film Miami Vice, which was again shot digitally, are considerable given the latter’s better reproduction of darker scenes even a year on. It’s perhaps the best happy accident of style and technology making a film better simply by virtue of not looking like cookie-cutter Hollywood product.

Collateral is a fascinating story of two disparate characters who collide one steamy LA night. The screenplay by Aussie writer Stuart Beattie (better known as the director of Tomorrow When The War Began and Golden Raspberry Nominee for writing GI Joe: The Rise Of Cobra) is a white-hot crime thriller that works beautifully most of the time, except in latter stages of the final act when time and space seem to shrink exponentially, contrivance and convenience of plotting override the film’s early brilliance, and Mann’s ability to humanise even the most inhumane of characters wanes a touch, bordering on Joel Schumacher-esque Batman & Robin-camp in parts. It’s undoubtedly a subgenre classic and worth the price of admission for Cruise playing against type as an out-and-out asshole villain, while Jamie Foxx is a delight as Max and bit-parts to Mark Ruffalo and Jada Pinkett Smith are worthwhile. Despite stumbling in its finale, Collateral is highly recommended for fans of crime noir thrillers and a stylishly modern take (for whatever its worth) on one of cinema’s most misunderstood genres.