Movie Review – Blue Skies

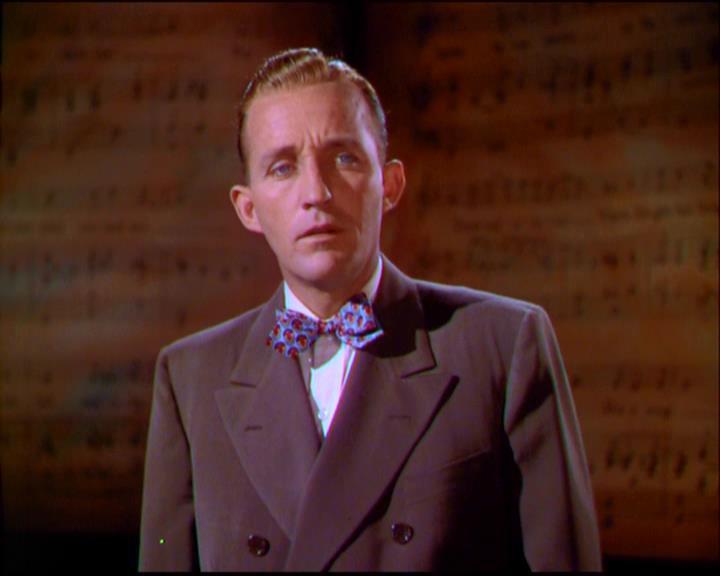

Principal Cast : Bing Crosby, Fred Astaire, Joan Caulfield, Billy de Wolfe, Olga San Juan, Mikhail Rasumny, Frank Faylen.

Synopsis: An ex-dancer and New York radio star narrates his love story for a band singer who loved a self-centered man who was unable to commit to his nightclub business or his family.

********

Touted as Hollywood legend Fred Astaire’s “final film” prior to release, Blue Skies formed a wonderful send-off for the iconic hoofer, but also as a platform for a series of delectable Irving Berlin tunes and Bing Crosby’s always amenable crooning. While the storyline might feel a bit naff by today’s standards, the positively baffling character arc for Crosby chief among the flaws, the inclusion of so many wonderful songs, so much terrific dancing, and a beautiful leading lady in Joan Caulfield, Blue Skies feels like an A-list event film despite a relatively low budget feel and a wonky directorial style.

Bing Crosby stars as a commitment-phobic nightclub owner, Johnny Adams, who catches up with former dancer-turned-radio-star Jed Potter (Astaire), who is telling his life story on-air (for some reason). Johnny, it seems, has a penchant for owning, then selling, nightclubs in the years just after World War I. This gypsy-like existence is a hindrance to his relationships, especially when he falls for band singer Mary O’Hara (Joan Caulfield), who is introduced to him by Potter, the latter of whom secretly loves her. Throughout the years, Mary and Johnny’s on-again, off-again relationship waxes and wanes, with the self-centered Johnny unable to commit to a settled life with his wife, or their children, or even his many nightclubs. It is revealed that Jed, after a failed attempt at a relationship with Mary, suffered a career-ending injury and fell into alcoholism, before turning to his radio career.

Blue Skies isn’t so much a dramatic musical film as it is a musical showcase for Irving Berlin, the iconic American composer and lyricist whose tunes have become legendary standards in the decades since; titles such as “Puttin’ On The Ritz”, “Cheek To Cheek”, and the eponymous “White Christmas” are instantly recognisable even today. Written by the composer, Blue Skies was directed by Stuart Heisler, best known at the time for his 1944 propaganda film The Negro Soldier, and sees almost every minute of this film include an Irving Berlin tune, be it ostensibly in the dozen or so songs sung throughout, but also in the incidental music (again, composed and conducted by Berlin himself). A cavalcade song film, Blue Skies doesn’t demand attention at all, as a superficially thin character drama plays out over the cannily linked melodies in such a way as to never treat the audience with diminished respect but rather with a warm embrace of familiarity – most, if not all, the songs included were already well known, just repurposed for this project, making Blue Skies feel effortlessly familiar to those watching.

One of the chief features of the film is the always enticing screen presence of Astaire, who seems to glimmer on the screen whenever he’s present. The charisma the man has with a film camera cannot be understated: here, approaching 50, Astaire inhabits a worn-out edge to his role but during one of the film’s most astonishing moments, dances to an updated “Puttin’ On The Ritz” number alongside multiples of himself that show just how awesome his gravity-defying physicality could be. And his forlorn love-story persona, whilst pursuing, losing, gaining and then losing Mary again, is apropos of the 1940’s style of romanticised tragedy. Joan Caulfield, for her part, holds her own alongside the more astute performers, adopting a coquettish nature throughout that makes her the apple of both men’s eyes.

Yet it’s Bing Crosby’s frustratingly selfish character that derails a lot of Blue Skies’ sense of fun. He’s indifferent to Mary’s charms when it counts (ie when the going gets tough, so to speak) and is easily bored by what he has right in front of him, always seeking… something else to entertain him. This is a difficult character trait to make feel worthy of a leading man – honestly, Jed should have slapped the baritone right out of him and moved on, whilst Mary deserved much, much better – and I had difficulty accepting that a man of Crosby’s indelibly soft-edged persona would stoop to leaving not just his wife but also his beautiful daughter (Karolyne Grimes) in such a cavalier manner. But he always rebounds, crooning his way through the film with that relaxed air we’re so used to, his blue eyes all dreamboat-like and making us forget that his character is an entirely reprehensible deadbeat.

There’s a sequence where Crosby and Astaire do an early-form sing-off battle, “A Couple of Song And Dance Men”, in which the pair tango around each other’s flaws and failures, that is absolutely wild to watch, whilst the film’s major production number, “Heat Wave”, boasts a staggering level of design, intricacy and thematic purpose, ending with tragedy. The more intimate songs are shot with a fairly standard era soft-focus by DP’s Charles Lang and Bill Snyder, using that wonderfully vaseline-smeared lens style to shoot close-ups and cutaways that kinda doesn’t mix well with the wide and midrange shots, but is effective for driving the sweetly bucolic story into each drooling musical number. Irving Berlin was terrific at lyrics, but in my opinion he was a master of melody, and Blue Skies has some (not all) of his best. The soundtrack alone is enough to make me nostalgic for a simpler time (admittedly, the film was released barely a year after the end of World War II, so not exactly a simple time by any stretch) and most of the songs have a resonance that supersedes the film entirely.

Blue Skies may not be the most accessible film – a knowledge of Irving Berlin’s songs is practically a must – but it is a charming little time-waster that features a blistering Astaire dance number, some terrific Bing Crosby crooning, and a packed-to-the-rafters jukebox of Berlin’s great compositions. As weary as Astaire must have felt, he was certainly far from actual retirement despite the film being marketed as such, and the story, while a little silly in spots, hits just the right note of genteel melodrama you never feel slighted by just how slight it truly is.