Movie Review – Seven Samurai

Principal Cast : Toshiro Mifune, Takashi Shimura, Daisuke Kato, Isao Kimura, Minoru Chiaki, Seiji Miyaguchi, Yoshio Inaba, Yoshio Tsuchiya, Bokuzen Hidari, Yukiko Shimazaka, Kamatari Fujiwara, Keiko Tsushima, Kokuten Kodo, Yoshio Kosugi, Shinpei Takagi.

Synopsis: A poor village under attack by bandits recruits seven unemployed samurai to help them defend themselves.

********

Revered as one of the greatest films ever made, Seven Samurai for the longest time formed a significant gap in my career in film appreciation. I have, of course, seen many a film for which Seven Samurai is the almighty ancestor, and so have you. Films such as The Magnificent Seven, Battle Beyond The Stars, Pixar’s A Bug’s Life, and even recent Star Wars series The Mandalorian have either outright used the plot or at least paid homage to the story to varying degrees. It’s a film referenced by almost all major Hollywood directors today as a key influence on their own careers, particularly the likes of Spielberg and Tarantino, and is routinely added to the top of many “best of” lists even to this day. Countless words have been written about its influence, its legacy and its purity as a film, which only adds to my reticence to adequately throw my own into the ring in singing its praises. Sings its praises I must, however, for Seven Samurai is exactly the masterpiece you may have heard it is.

Japan, the 1580’s, and a rural village is fearful of a band of bandits who plan on raiding their homes after the next harvest. The village patriarch (Kokuten Kodo) suggest sending a small group to the nearby city to recruit several ronin (masterless samurai) to their cause in protecting the village. Master Kambei (Takashi Shimura) is a war-weary samurai veteran who accepts the villagers’ invitation, and alongside his loyal deputy, Shichiroji (Daisuke Kato) and the gregarious Kikuchiyo (Toshiro Mifune) and four others, arrive at the small settlement to train its inhabitants to fight and protect their families from the marauding band. In the interim, a young disciple samurai, Katsushiro (Isao Kimura) falls for local farm girl Shino (Keiko Tsushima) much to her father’s disgust, whilst Kikuchiyo decides to infiltrate the bandit horde and strike a blow before the attacks.

There are all manner of themes and ideas floating around inside of Seven Samurai, most of which I’m probably not eloquent enough to elucidate. What I can tell you is the film is one bursting with intriguing characters, a sense of isolation, loss and fear, as well as a rising emotional state of brotherhood, something the titular ronin – samurai who have lost their masters – feel by the end of the movie. Kurosawa’s direction is a masterclass of structure, framing and editing, the screenplay (by Kurosawa, Shinobu Kashimoto and Hideo Oguni) fluctuates with despair and honour, and the performances are roundly excellent, bordering on exemplary. Clocking in at well over three hours, Seven Samurai is a slow-build dramatic story working towards a blistering combative climax fuelled by rage and filled with death, but you never really feel the time stretching. It’s the kind of film you soak in, like a good mud bath or spa, allowing the fragrance and visuals of Kurosawa’s mastery of the camera to wash over you completely.

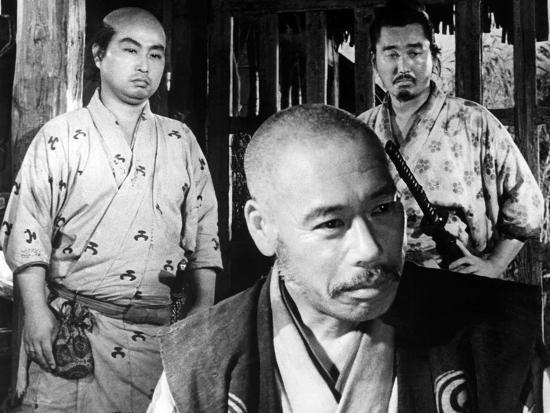

Although colour film had arrived in Japan in 1951, with the debut of Carmen Comes Home, Kurosawa chose to shoot Seven Samurai in black and white and the atmosphere this decision provides is iconic. The director’s use of framing for interiors, often having all seven samurai within a single frame in different “layers”, and frequently having the central figure with his back to camera, offers a dynamism more traditional filming techniques lack. The way the light plays upon the central figures in the film, casting shadows and spotlights on each character, indicates emotional content and forms a secondary storytelling canvas upon which the director powerfully accentuates his stars. The climactic battle sequences, of which there are a surprising number – Japanese culture of the day apparently had a “surge and retreat” attack style, returning multiple times to try and wear down the opposition – don’t feel choreographed as much as they are haphazard, with Kurosawa’s camera during these more energetic moments relatively isolated from the action to a large degree; this marks a different approach than that with which he films the dominant exposition and “character” sequences of the film, close and intimate and allowing each actor to inhabit their roles utterly. Such stark difference between the quiet and the battles gives the latter a frenetic realism, a who-will-die tension as men on horseback ride through the mud-soaked village on what appear to be suicide missions.

For me, though, it’s Seven Samurai’s quiet languid language of honour and hubris that works so beautifully. Although the film never outright stipulates the ronin’s pain at being ostracised, their dishonour is rectified by their actions in keeping the village safe from the roaming bandits. Each of the seven have specific characteristics, some more prominent than others (Mifune comes across as a bit of a dick at first, but by the latter stages feels more like a legitimate member of the group despite not quite fitting with samurai zen-like precision), and to a workable degree Kurosawa allows each their “moment” to shine within the film. I really liked Takashi Shimura’s calm, reasoned leader of the group, Kambei, a man for whom battle is a way of life despite never wanting to actively participate; a master strategist and honourable man personifying the samurai legacy, Kambei’s arc isn’t so much intrinsic to himself but rather a father figure to those who follow him. In many ways, Mifune’s charismatic Kikuchiyo and Shumira’s Kambei form a yin-yang dynamic for the assembled seven, offering different approaches to a problem that inevitably work well enough together to overcome the odds.

I also really enjoyed the arc of young samurai disciple Luke Skywalker Katsushiro, played wonderfully by Isao Kimura. Kimura’s youth and infectious zeal in becoming a samurai, and protecting the village, is offset by his ignorance to the deadly nature of battle, and his infatuation with the beautiful Shino is one of the film’s highlights. I thought his performance during one of the film’s more sombre moments, when Shino’s father beats her for sleeping with Katsushiro (thus, becoming “damaged goods” in Japanese honour culture) was restrained and excellent, even if he utters nary a single word. So too is the restraint show by Seiji Miyaguchi, who plays the stone-faced swordmaster Kyuzo. He’s undeniably the “badass” character of the film, somebody with exceptional skill who only uses it when he has to. Miyaguchi has this magnetism to his screen presence, giving off a subliminal strength that resonates right through to the final battle.

One of the things I generally struggle with in most Eastern Cinema is the music; I’m not a fan of plinky-plinky Japanese scores and I was all set to dislike Seven Samurai because of this. It’s a prejudice I’m not afraid to admit to, mainly because I think it comes down to personal taste, and my tastes don’t lean that way. Seven Samurai has a truly masterful musical score by Fumio Hayasaka, one that disappears into the film so subtly you don’t even notice it. Nuanced and elegant, I may have a hard time humming it but for the context of Seven Samurai it is beautifully written. It’s not so much plinky-plinky as it is ethereal and captivating, a haunting melodic work accompanying the on-screen visuals perfectly. Speaking of visuals: longtime Kurosawa cinematographer Asakazu Nakai’s photography here is, in a word, exceptional. It’s a work of art, this film, from its production design, makeup and costuming, but without Nakai’s prowess behind the camera Seven Samurai would be a lesser film. The way the film uses light and shadow, the way it uses focus in large ensemble sequences, the way the camera moves in action sequences and to heighten tension within a specific moment, is remarkable indeed. There’s a showmanship, an operatic vivacity behind the camera here, and whether it was entirely Nakai or a little bit of Kurosawa himself the end result is stellar.

Seven Samurai is a film often described as a masterpiece and I’m here to reiterate that statement one hundred percent. It’s the kind of film you need to invest entirely into, not a film you can watch half-assed whilst tweeting that meme at your friends; at over 200 minutes you’re going to need a catheter to survive it, but it’s well worth the bodily disharmony. Compelling characters, a baseline plot and Kurosawa’s powerhouse direction (the film’s production was shut down several times, according to the director, who simply went fishing in the interim knowing the suits would realise their investment was so considerable they’d need it to be completed to recoup their expenditure) as well as indelible performances make for a film it’s impossible not to enjoy and appreciate. Seven Samurai is evocative and entirely wonderful. What a great film!