Movie Review – Sherlock Jr

Principal Cast : Buster Keaton, Kathryn McGuire, Joe Keaton, Erwin Connelly, Ward Crane, Ford West.

Synopsis: A yound cinema projectionist dreams of becoming a world-famous detective.

********

You might be surprised to learn, as I was, that Buster Keaton’s 1924 comedic short film Sherlock Jr, in which its star daydreams of becoming a great detective in the mould of Conan Doyle’s eponymous Sherlock Holmes, was met with mediocre critical and popular success. It certainly wasn’t considered the masterpiece status it is afforded today, which goes a long way to understanding more how tastes wax and wane down through the years. Sherlock Jr isn’t just a great short film, clocking in at a brisk 45 minutes, it’s a flat-out masterpiece of technical astonishment, comedic timing and physical stunt-work that reportedly almost killed Keaton midway through filming.

Keaton plays a young cinema projectionist, who has a fancy for the wealthy daughter (Kathryn McGuire) of a businessman (Joe Keaton), only he lacks the cash to woo her. The Girl is courted by a local Sheik (Ward Crane), himself skint but also clever enough to pilfer an expensive watch and cause the projectionist, who dreams of becoming a detective like Sherlock Holmes, to be banished from the Girl’s home. As he daydreams at work, the projectionist enters a lavish film set and performs numerous stunts in the guise of a great detective, with the “film” populated by people from the real world in key roles.

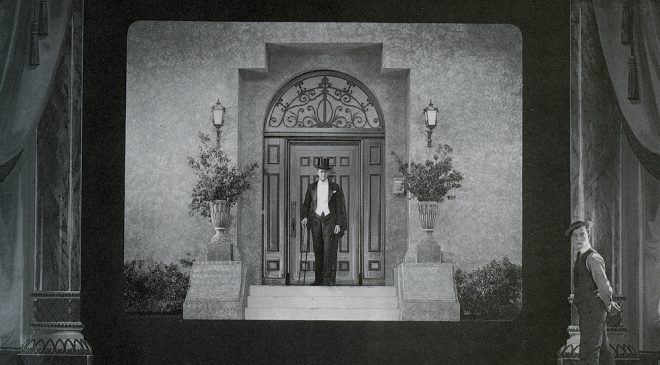

Arguably Keaton’s crowning achievement in the short film genre he starred in, Sherlock Jr is a witty, daring, occasionally awe-inspiring technical and comedic achievement. Few films of the period (that I’ve seen) have the talent to put the great Charlie Chaplin in the shade, but Keaton’s Sherlock Jr achieves this, with eye-popping visual effects (including a clever early use of double exposure to set off the “dream” motif) and Keaton’s trademark physical stunt work actually making you question how they achieved all they did. The short also establishes an early precedent for a “film within a film” idea, with Keaton’s character entering into a film playing at his cinema, and cavorting through a series of well-staged comedic edits to appear to be inside the film frame.

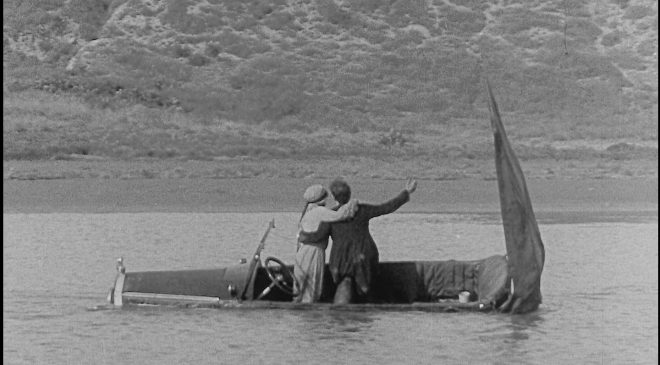

Like many short action films of the period, Sherlock Jr is built on a semi-romantic premise of “getting the girl”, with Keaton’s deflated hero down on his luck just enough that he has to wangle his way into the charms of the lucky lady. It’s as generic a story hook as you’ll find, yet it plays to very well in Keaton’s capable hands. Ward Crane’s dastardly villain character, slick hair and gleaming good looks, is an archetype of simplistic screen antagonists, and against Keaton’s more gangly frame and physical comedy he’s a perfect straight man. Kathryn McGuire’s unnamed female lead is just doe-eyed enough to elicit the response from both Keaton and Crane to warrant the antics that ensue, and with a relatively slow and confusing start the film quickly fires up to deliver some truly remarkable filmmaking.

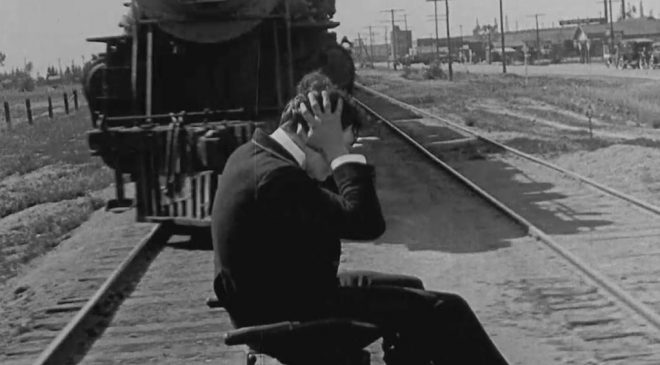

The film’s first significant wonder is the lengthy sequence in which Keaton’s character enters into a film, obviously built as a practical set on the filmmaker’s Hollywood backlot and remarkably effective considering the absence of computers to enable such trickery. A series of montages, in which Keaton ambles through a series of scenes that “cut” together to produce some delightful physical comedy, are exceptionally well executed and must have been a royal pain to pull off. There’s the period’s usual clown-car tomfoolery, with Keaton at invariably putting himself into harms way to deliver great laughs or thrills, including riding the handlebars of a motorcycle through the streets of a youthful Los Angeles completely unaware his driver has fallen off way back, and coming perilously close to being cleaned up by an oncoming train. There’s also a cute moment where Keaton runs along the roof of a train in the opposite direction, running out of carriages until he dangles precariously from the spout of a water-tower, which inevitably gives up its liquid contents and nearly drowns Keaton in a torrent. Remarkably, it was during filming of this sequence that Keaton, unaware of the force of the water awaiting him, would nearly break his neck in the ensuing flood and notoriously had severe physical complications for years afterwards.

There’s a lengthy game of pool in which the Villain, together with his Butler (Erwin Connelly) attempt to assassinate the Detective Keaton with exploding billiard balls, only to discover that the Detective is a pool-playing genius and avoids imminent death. At one point there is also an amazingly inventive quick-change moment, as well as one of the most startling rewind-and-rewatch moments of vaudevillian physicality I’ve ever seen; there’s so much going on in Sherlock Jr you’ll likely miss something and find new things upon more rewatches. And it’s all so impeccably timed, so perfectly edited and so wonderfully acted by the entire ensemble, it’s little wonder the film is so highly regarded by Keaton fanatics today. It really is a film filled with such technical 1920’s wizardry behind the camera (the film was co-directed by William Goodrich, who gets a credit, and Keaton’s mentor Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle – then trying to re-establish himself following a (false) rape allegation – who does not), showing off the daring physicality of Keaton whilst treating the viewer to some wonderful visual effects and tricks.

Sherlock Jr is a masterpiece of the format. It sets up the story well, slides into fantasy with ease, before giving us what is hands-down the most breathtaking series of stunts and comedic pratfalls I’ve seen in any silent film to-date. The descriptive title cards keep the story developing but, like a good short film ought, the story doesn’t really need them, with Keaton flexing his considerable creative talent to ensure the laughs and thrills are maximised as best as possible. Immensely enjoyable, with a timelessness and honesty of the day, Sherlock Jr is one hell of a fine film from one of cinema’s most accomplished creators.

Just a quick note: William Goodrich is Roscoe Arbuckle. That was the pseudonym he came up with as a play on Keaton’s joking suggestion of “Will B. Goode.”