Movie Review – Broken Blossoms

Principal Cast : Richard Barthelmess, Lillian Gish, Donald Crisp, Arthur Howard, Edward Peil Sr, George Beranger, Norman Selby.

Synopsis: A frail waif, abused by her brutal boxer father in London’s seedy Limehouse District, is befriended by a sensitive Chinese immigrant with tragic consequences.

*****

Startling silent film from cinematic pioneer DW Griffith, Broken Blossoms is a thematic and technical powerhouse production and boasts early roles for industry icons Lillian Gish, Donald Crisp and Richard Barthelmess, the latter of whom appears in the lead role of a oriental figure living in downtrodden Edwardian-era London despite being as European-looking as it’s possible to be. While better known for racially problematic film The Birth of A Nation and his corrective opus Intolerance, Griffith’s 1919 film contains issues of race some might find problematic (but specific to the era) and a heartbreaking rendition of domestic abuse, yet steels itself against such darkness with a moody, evocative romantic storyline that almost makes the salacious elements of the film worthwhile.

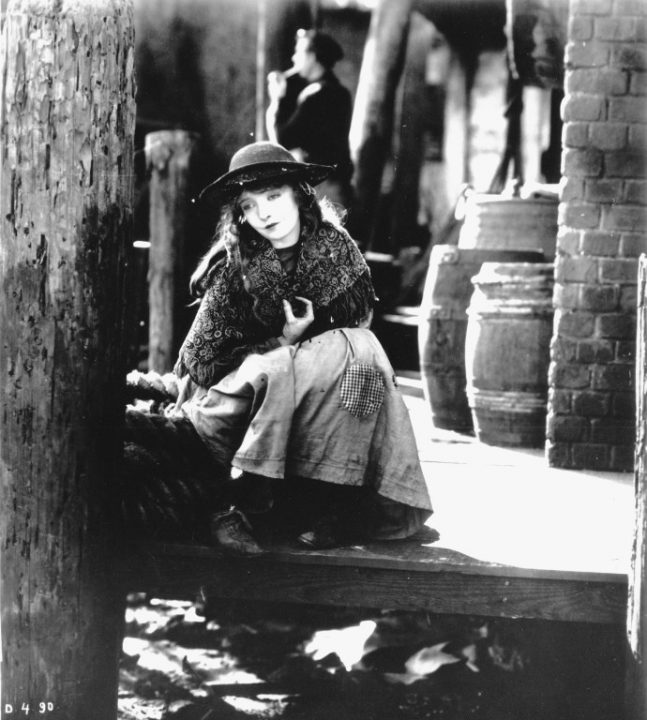

Plot synopsis courtesy Wikipedia: Cheng Huan (Richard Barthelmess) leaves his native China because he “dreams to spread the gentle message of Buddha to the Anglo-Saxon lands.” His idealism fades as he is faced with the brutal reality of London’s gritty inner-city. However, his mission is finally realised in his devotion to the “broken blossom” Lucy Burrows (Lillian Gish), the beautiful but unwanted and abused daughter of boxer Battling Burrows (Donald Crisp – How Green Was My Valley).

It’s worth noting that Broken Blossoms, which tells of an interracial romance (although the two actors were both white) came out at a time when America was gripped by the pervading “yellow peril“, so the success of this film kinda refutes the idea that an entire country was prejudiced against those of Asian descent. Still, despite a generally anti-racist plot, the film’s pervading sense of its period remains laughably offensive to modern eyes, with the constant referral to Cheng Huan as “the Yellow Man”, with yellow being the pejorative word for an oriental, while “chink” is utilised a lot. The downtrodden Lucy, played by Gish, is a waifish, innocent young thing, and the film’s prevailing arc is a kind of reverse white-saviour story, in which a near-anonymous asian fellow working the skanky streets of London’s eastern boroughs “saves” Lucy through love, so it makes for interesting viewing today.

The screenplay is written by Griffith himself, based on a play by Thomas Burke called “The Chink & The Child”, which only goes to show how problematic the film might seem to be to our eyes now, but if you can overlook the political un-correct-ness of Griffith’s film there’s a sweet-natured nostalgic flavour to the tale that works beautifully. Yes, the language used within the film is persistently racist, and the few supporting roles of ethnic truth we see are effectively minuscule, but the heart of the film’s story is palpably romantic despite problematic period-era issues.

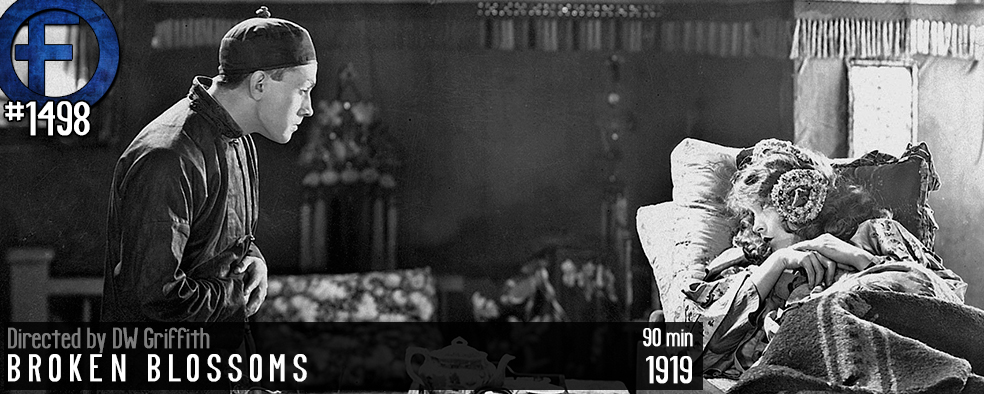

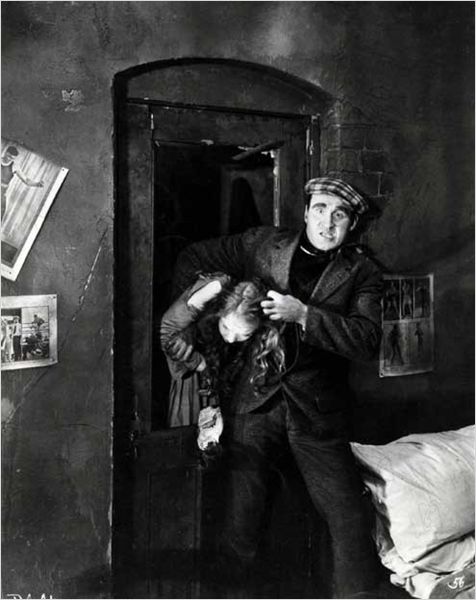

There’s a chemistry between Gish and Barthelmess to savour, which is key to the film being bearable. Gish, as Lucy, engenders sympathy almost immediately, opposite her domineering father in boxing champ Burrows. Donald Crisp, who was only 11 years older than the actress playing his daughter, is thoroughly menacing with his cauliflowered ear and high-waisted britches, and his physicality on screen is faultless. Barthelmess, whitewashing aside, is decent as Cheng Huan and his doe-eyed gaze at Lucy throughout endears him, where it could be utterly creepy. Conflict arises through Lucy and Cheng’s love, obviously through “Battling” Burrows’ masculinity and sense of pride (misplaced as it is) refusing to admit that an oriental could possibly love his daughter (or, perhaps, that his daughter could love, period) and Griffith elevates tension through this gradually rising sense of threat. While its romantic interludes are genteel enough, the brutal nature of Burrows’ abusive behaviour – and Donald Crisp’s fearless commitment to performing it – are in stark contrast to each other.

Whether intended or not, Griffith’s film today tackles subject matter that must have felt almost taboo to audiences of the day. Today we call this xenophobia, or the fear of something (or someone) which is foreign, and although the story isn’t strong enough to capitalise on such elements, it’s worth noting how prescient Broken Blossoms might feel to our eyes now, a century after its debuted. In many ways, it’s incredibly sad that such thinking hasn’t disappeared from our culture, and has only grown more virulent and destructive. The idealised love between two disparate people, who might not otherwise have found each other, is romanticised by Griffith’s use of tinting the film – scenes between Cheng and Lucy are rendered with a sweet pink hue, nighttime sequences come with blue, and the rest of the film is sepia-toned – and the director’s use of camerawork and editing is revelatory.

Griffith was a pioneer not just in silent film but in film generally, using a mix of close-up and wide shots, reverse angles and deep-irised footage to capture his story. Typically for the period, the camera doesn’t move (never tilts, pans, dollies or anything that would upset the mechanism inside the camera) so Griffith uses cuts to move his camera closer to or further away from the action. This elicits inherent tension in a scene – especially those in which Crisp’s character berates and bludgeons Gish’s Lucy – and it’s a visceral, effective tool at his disposal. Although previous and future films would display considerably more prowess and skill, this smaller, intimate story lacks not for Griffith’s sharp-eyed cinematic acuity.

Broken Blossoms is an effective effort from silent film pioneer DW Griffith, and despite some problematic phrasing and terminology within its screenplay, there’s a lot to like about it. Moody and atmospheric, ripe with nascent romantic interludes and a commanding villain performance by Donald Crisp, Broken Blossoms is an indicative escapade from the formative cinematic period of the day. Well worth a look.