Movie Review – Apocalypse Now: Redux

Principal Cast : Martin Sheen, Laurence Fishburne (credited as “Larry Fishburne”), Marlon Brando, Robert Duvall, Frederic Forrest, Dennis Hopper, Harrison Ford, Albert Hall, Sam Bottoms.

Synopsis: Colonel Ben Willard is sent by his superiors to locate, and kill, a potential rogue officer living far up the Nung River during the Vietnam conflict. Along the journey, he encounters all kinds of bizarre situations and characters, adding to his own tortured psyche, until the final confrontation between him and his assignment threatens to send him over the edge himself.

******************

There are two moments in Apocalypse Now that have entered the pop-culture zeitgeist, moments that are spoofed, parodied and played upon whenever somebody wants a historical touchstone for war, or the madness of it. Robert Duvall’s oft-quoted line about loving the smell of napalm, and the epic helicopter attack utilizing the score for Wagner’s Ride Of The Valkyries. However, ask anybody under the age of around 25 what films they come from, or indeed anything else about that film, and you’ll probably receive a blank look. Which is a shame, because Apocalypse Now is a film worthy of inclusion into whatever pantheon of Great War Films you seek to fill. Director Francis Ford Coppola suffered a nervous breakdown whilst filming this monster, star Martin Sheen had a heart attack, and Marlon Brando…. well, behaved exactly like Marlon Brando would; yet for all its famed production troubles (and I use the term “troubles” in the lightest sense, because this was an apocryphal film to make) Apocalypse Now remains an enduring icon in Hollywood’s history. Today, we take a look back at the film itself, look beyond the anecdotes and myths, to see if it really does hold up after all these years.

We’ve decided to review the longer “redux” cut of the film, since this is the version preferred by Coppola himself, apparently. By adding 49 minutes of additional footage into his famed masterpiece, re-editing scenes and ultimately, changing the tone and character of the film, the Redux Version is considered by many critics to be a different film altogether. I tend to disagree, although only to a point. The Redux Version isn’t an entirely different film, rather, it’s a more complete version (a la Peter Jackson’s Lord Of The Rings Extended Editions) which enhances and strengthens the film overall. Some will see the addition of nearly an hour of extra footage to be some sort of desecration of the original, although I think that both the original cut, and the Redux cut, can be now viewed in the same light as the aforementioned Jackson epics. The same film, just extended. People can feel free to disagree with me if they want, but that’s the modus operandi for this review, take it or leave it. [Editors Note: There are a number of different versions of Apocalypse Now floating about, according to the Internet. One, a bootleg video version, runs around 289 minutes, and apparently there’s an even longer 330 minute workprint version out there too, all on low quality video.]

I wasn’t the right age to see this film when it first came out in 1979 (I was only 4), and I’ll go on record as saying that when I finally did get to see it, I wasn’t all that impressed. I was just finishing school, when I saw the original version, and the concepts and style of the film annoyed me, and confused me. Especially Brando’s mumbling portrayal at the end. I guess by that stage I’d had it built up in my head as some kind of masterpiece of film, a film that would redefine my concepts of what was possible on-screen, a kind of game-changer, to use a more modern phrase. At the time, though, Apocalypse Now simply disappointed me. With time and age comes maturity, however, and years later (back in 2001, I think it was) got to see the re-edited Redux Version in the local cineplex. It was only then that I got it. I’d become more of a film buff by then, and could readily appreciate the nuances, the technique, the style of the film, with a more positive outlook. And I was amazed at what I saw. After witnessing this Redux-ified film, I immediately went to my local video store and hired a copy of the documentary which accompanied the film (shot while Apocalypse Now was being made, and narrated by Coppola’s wife, Eleanor), Hearts Of Darkness: A Filmmaker’s Apocalypse. This doco showed just how hard it was to make Apocalypse Now, a trial of endurance, both physical and mental, in one of the worlds harshest environments; it drove home to me just how epochal Apocalypse Now is as a film experience.

Colonel Ben Willard (Martin Sheen) is a man on a mental precipice. His post traumatic stress disorder has manifested itself with some severe alcoholism and drug dependency: as the film opens he’s in a near catatonic state, due to his front line experiences in the Vietnam conflict. His superiors, sensing perhaps a chance to exploit his fragile mind, send him on a mission up the fictional Nung River to locate a fellow officer, Colonel Walter Kurtz (Marlon Brando), who he is told has gone rogue. His mission is to locate Kurtz, and terminate the Colonel’s command. Willard joins a team on a patrol boat, and begins his journey up the river. In what becomes an epic journey, Willard begins to question his orders, the motives of those around him, and even his very sanity, as he struggles to understand a war as pointless as it is needless: his witness to the dehumanization of those around him is powerful indeed.

Coppola based his epic war film on the Joseph Conrad story Hearts Of Darkness, transplanting the original book about the 19th century British man assigned to captain a ferry-boat in “darkest Africa”, to a man journeying on a river boat through darkest Vietnam. And indeed, Apocalypse Now is a very dark film. Moments of it are cinema at its finest, while others remain fragmented, fractured narrative at best. There will be those who say I am crazy to criticize this film, for every frame is a masterpiece in and of itself. I tend to disagree, for the Redux Version of Coppola’s monster of a film is nothing if not a flawed vision; albeit an entertaining one. A warning to the uninitiated, however: the Redux version clocks in at a staggering 202 minutes, which is around the same running time as the theatrical version of Return of The King. In racing parlance, it’s a marathon, not a sprint. So take a cup of warm milk and biscuits into this one.

The film begins with perhaps one of the most iconic opening sequences ever: a tropical treeline, the thwup thwup of Hueys flying past the screen, the discordant sounds of The Doors classic “The End” slowly fading in, before the jungle erupts in an enormous gout of flame. Cut to a hotel room in Saigon, where Colonel Willard sits, his mind nearly broken by unknown horrors, slowly flipping out. Willard is a wreck, a drunken, possibly suicidal mess, and it’s only with new orders from command that drags him from his room and back into combat. It’s hard to understand what’s going through Willard’s mind at times, because he remains predominantly a passive observer of all that takes place throughout the film: save for the climactic confrontation at the end. The war, and all it’s glorious madness, is personified by the varied characters Coppola puts into the film throughout. Robert Duvall, in particular, has a great time chewing the scenery as Lt Colonel Kilgore, a slightly mad officer who’s disregard for danger makes him the perfect leader. Kilgore gets one of the films most iconic lines, the “I love the smell of napalm in the morning” one, and Duvall is pitch perfect. The madness of his situation, trying to normalize things around him whilst doing unspeakable acts of violence, is indicative of the entire film. People, in war, do terrible things, dehumanizing things, and Apocalypse Now is the very best example of that. The river boat that Willard uses to get upriver to Kurtz is crewed by the best and worst of humanity during war: the stoic chief (Albert Hall), who’s authority on the boat cannot be questioned, and a highly moral man who does his job with the best moral compass he can; Clean (Fishburne), the representing the disillusioned youth who thinks of war as his birthright; Chef (Frederick Forrest), the tightly wound soldier at breaking point from the horror of battle, a man who detests what his country has forced him to do; and finally, Lance Johnson (Sam Bottoms), a former pro surfer from California who would rather suntan than fight.

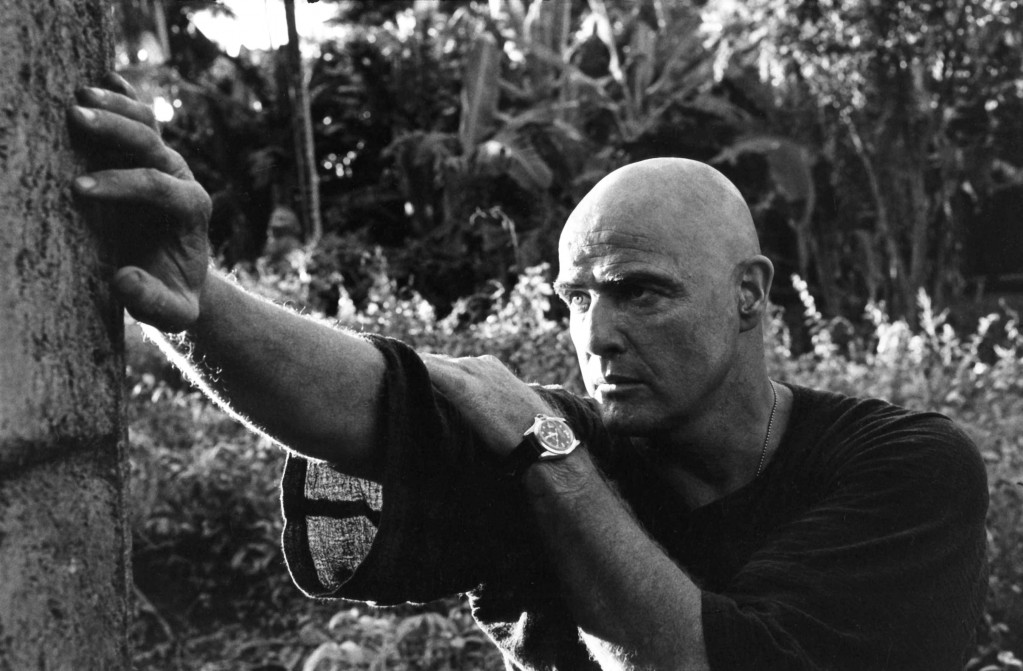

Marlon Brando, as Kurtz, the main antagonist in the films final act, is something of a cinematic enigma. The Kurtz character is built up over the course of the film to be an almost mythical, god-like figure of madness: Brando’s bald, sweaty portrayal is about as powerfully mad as Pee Wee Herman on acid. The final confrontation is so anti-climactic it’s truly disappointing. Perhaps that’s the point, though. Perhaps Kurt’s status and reputation isn’t what we first thought, a narrative about-face intended to highlight how little we understand about ourselves: Willard’s mission to kill Kurtz isn’t as clear-cut as we first thought. Over-thinking this plot thread, though, isn’t conducive to understanding it. It’s hard to understand if Brando is just making it up as he goes along, and his four (admittedly brief) scenes don’t really do the rest of the film justice. Just what the hell he’s talking about isn’t very clear. Or interesting. The same could be said for the unnamed US photojournalist, played by Dennis Hopper: his ramblings and pseudo-psychobabble becomes somewhat monotonous and repetitive. He’s obviously a believer in Kurtz’s cause, but exactly what he thinks Kurtz’s cause is is a little uncertain.

By far and away, though, this film belongs to Martin Sheen. His portrayal of Willard is wonderful, albeit undone by some confusing character moments. Generally, you can feel the underlying rage against his situation, even if the character himself states (during an opening narrative voice-over) that he feels more at home here in Vietnam than he does back in the USA. Outwardly, he appears calm and easy-going (to a point), but sometimes he snaps with rage (case in point: he drags a supplies clerk over his desk with a snarl to obtain some more fuel for the boat, before returning to his calm, calculating ways) and becomes a monster – perhaps the monster he’s destined to become to kill Kurtz when they meet. Willard’s internal struggle to connect the insane ramblings of Kurtz played to him at his mission briefing, and the personnel file he takes with him as a study, is the key element to his journey. He must find it within himself to commit the ultimate crime – murder – for the sake of the army and for those in Kurtz’ thrall. As a soldier, this would be easy, you’d think. but as a human, it’s much harder. In some ways, Willard finds himself empathizing with Kurtz’s decision to go off the radar, because for him, perhaps, it’s the easiest way to survive the un-survivable conflict. Martin Sheen’s understated performance holds this film together, the linchpin of the story that doesn’t always involve him directly, but rather revolves around him. As such, his reaction to events is key to his emotional core, and to us as an audience going on this journey with him. Sheen is an actor of such power, he doesn’t need much more than a glance, a look, a groan or a snarl, to elicit such a reaction from us. This isn’t a hysterical performance: nor should it be. Willard’s inner strength, when by rights most other men would have given up and gone quietly mad, is resolute, and his strength gives us strength.

Among the scenes Coppola reinserted into the Redux is a series of scenes involving a couple of Playboy bunnies, one of whom is played by Colleen Camp, who is best remembered around the fernbyfilms.com offices as Yvette the French maid from Clue. Of all the reinserted stuff, these scenes are the most poignant. The brutality of war, the madness of it all, is wonderfully counter-pointed by the frenzy of Playboy bunnies arriving for a show to the soldiers at base camp; it’s even more emotional when the boat crew stumble upon them again in an almost deserted base awaiting evacuation after their helicopter runs out of fuel. The off-kilter sexuality of the women in this hell-hole of a war is dreadfully sad and somehow beautiful. But by far the most obscure sequence re-inserted by Coppola is the French Plantation scenes, of which there are a large number. When Willard and the boat crew arrive to discover a French plantation still being run by a family, they stay and dine with them, before Willard is seduced by one of the female residents. A long, protracted and often intolerably indifferent conversation about French/US relations, the madness and insanity of war, as well as general French whinging, are played out in a sequence that, I’ll admit, has very little to do with the rest of the film. It’s strange, but I couldn’t see the point of it, and if there was one, I wonder what it was. Willard barely interacts with these people, probably even less than the crew of the river boat, and the scenario is a stark contrast to the more linear narrative that has come before. The French plantation sequence is definitely one I would have cut from the finished film if I was directing.

Apocalypse Now isn’t an easy film to “enjoy”, in the true sense of the word. Like the filmmakers and the cast, watching this movie is a test of both endurance and concentration. There’s moments of nuanced quiet, the dazzling scenery a sharp backdrop to the bloody warfare raging throughout it. There are also moments of grandiose, epic film-making from Coppola, the staging of which (all without the benefit of digital technology) must have been a feat in itself. The famous Valkyrie sequence, with the chopper attack on the Viet Cong outpost, is a testament to Coppola’s vision: it’s a powerful, confusing and violent eruption on screen. The river boat crew, who are on board the choppers for the attack, watch on in awestruck wonder as the American military machine cuts a swathe through the Vietnamese defence. The crass gung-ho attitude of the airborne soldiers, their cavalier attitude to their job and the consequences, is indicative of Coppola’s obvious intent to contrast the dehumanization of our leading cast by the end of the film. Of particular note, Sam Bottoms’ surfer dude Lance is terrified of the carnage around him, even though he takes it in his stride. By the end of the film, he’s mentally broken, a shell of a boy with little regard for his own safety, or even the safety of others. His journey in particular is, next to Willard’s, the most intense.

I use the term “intense” to describe this film to others a lot: there’s a lot of subtext going on here, and if you dig deep into the film’s more intimate themes, you’ll find more than a simple epic war film. Apocalypse Now, probably in either iteration, is a film that stays with you, long after you’ve finished it. I found myself humming various Doors riffs for a couple of days later, and contemplating moments in the film myself, what would I do, how would I react, if I were in that situation. The many haunting images in Apocalypse Now, the most enduring of which would be Willard’s emergence from the muddy, steaming river, his face painted in military war paint, impact subtly on your subconscious, you don’t expect it, nor can you understand it immediately afterwards. The final, brutal slaying of a bull, the seething crowd and tribal mentality of Kurtz’s “kingdom”, intercut with Willard’s confrontation with the mission he’s undertaken, is evocative and confronting: there’s no way PETA or the American Humane Society would have touched this film with a twenty foot p0le. But the bloody conclusion, the silent, melancholy motif afterwards, all add profound weight to the epic story which has unfolded before us. As a lover of cinema, it’s a film indelibly burnt into my psyche.

On the technical side, there are plenty of things I can say to make any budding filmmaker want to watch this film. Cinematically, this film has been released in both 2.35:1 and 1.33:1 aspect ratios during its long history: the Redux version is presented to us in the directors preferred 2.10:1 aspect. Coppola uses plenty of crossfades to move the action along, an old-school style of film-making that allows him to acknowledge the passing of time between scenes, or the fluid nature of consciousness (which is how I’d describe Willard’s opening scene in the hotel). From a cinematography outlook, the film really bucks the trend. Filled with anamorphic lens flare (the oblong ovals of light associated with the use of anamorphic lenses during photography) to a wildly rebellious level, there are (or would have been) a few professional film-makers who looked at this movie as a “how not to” use a camera. Historically, it’s the cinematographers job to avoid lens flare where possible, however Coppola (and DOP Vittorio Storaro) eschewed this “tradition” in favour of a more documentary-like feel. Many sequences shot during the night-time are particularly artistic, with almost every light and focus pull involving lens flare and the unique anamorphic distortion to enhance the final look. Nowadays, lens flare has become something of a defacto lighting style, thanks largely to influence of music videos and directors like Michael Bay and JJ Abrams. Editorially, Apocalypse Now Redux is superb, with editor Walter Murch reappraising his previous work alongside director Coppola to insert the “new” footage. The film isn’t a swiftly moving action piece: it’s human character study affords Murch the time to give these characters room to grow, to develop as people we come to understand and love. The editing is intimate, epic and everything in between. The film’s soundtrack, while containing a few music cues from era-centric popular music (Suzy Q comes in for a run, as well as The Doors), is predominantly a synth/orchestral score from Carmine Coppola (father of the director) and the director himself. While not a traditional score by any sense, the moody, atmospheric “instrumental” soundtrack gives enough discordant magic to the imagery, that it simply works. Predominantly a lot of twangs and thumps on drums and plucked instruments, the Coppola score is unique in it’s ability to convey the enduring madness of the story, and to never quite overstate itself.

Unfortunately, there will probably be people alive today who won’t “get” Apocalypse Now, in either its original version or the longer Redux. They won’t get it because the film isn’t an obvious one: it’s themes and ideas aren’t bubbling close to the surface like a Michael Bay movie. Francis Ford Coppola challenges us with Apocalypse Now, challenges us a lot. You need to approach this film with an open mind, and a mind ready to experience something that isn’t easy to like. It’s a film with a message, of that there is no doubt. But exactly what that message is, appears to change from viewer to viewer, and even from viewing to viewing for some people. A bafflingly obscure finale, with a shadowy, creepy Brando delivering lines which appear to make no sense, and some intense, ferociously produced battle/conflict sequences, make Apocalypse Now an experience more than a film. If you enjoy a film that makes you think, a film that challenges your idea on both war, and film itself, then this is a movie you need to see. As I mentioned, there will be those knockers who go away from this wondering what on Earth they wasted 3+ hours of their time for, and that’s fine. Those people aren’t ready for this movie. I was once in that position, because the first time I saw it, I felt the same way. But now, after I’ve matured and become more accepting of alternative forms of storytelling on film, I can appreciate Coppola’s monumental epic, and appreciate it for what it is: an examination in inhumanity, and what it takes to get us there. Devastatingly beautiful to watch, evocative and epochal in equal measure, Apocalypse Now Redux is not the perfect film, but it is the most impressive you’ll see for a long while. I loved going back up the river again, but I can understand why some people don’t.

For a final word, I’ll give it over to Colonel Kurtz.

“The horror. The horror.”

Came across this review while searching for Apocalypse Now images on google! No matter what version I think Apocalypse Now is a very powerful film about the sheer futility of war. The madness inherent in this film sums up the craziness of the war and those that continued to send patriotic soldiers to their deaths.

Thanks, Dan! I watched this film again only a couple of weeks ago, and it still manages to appall me for its depiction of this brutal, terrible war. From memory, Australia introduced conscription into the army as a way of boosting the number of soldiers we could send across – had they realized then what the cost would be now, perhaps people might have thought differently…..