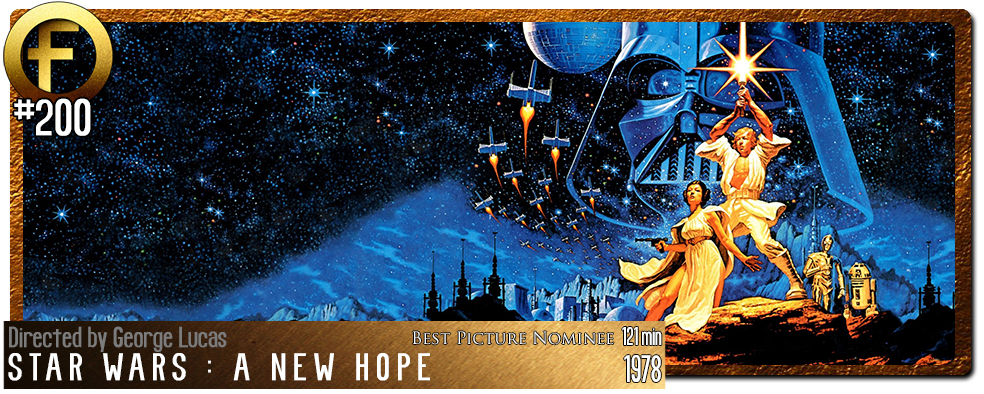

Movie Review – Star Wars: Episode IV – A New Hope

Cast : Mark Hamill, Harrison Ford, Carrie Fisher, Alec Guinnes, Anthony Daniels, Kenny Baker, David Prowse, James Earl Jones, Peter Cushing, Phil Brown, Shelagh Fraser, Denis Lawson, Jack Purvis, Richard LeParmentier.

Synopsis: When a tempestuous youth is taken on a galaxy spanning adventure, he has no idea that he is part of a larger destiny, and that his life will have an impact on the entire universe. Darth Vader appears here too.

******

Poor George Lucas. He had such a hard time making Star Wars I wouldn’t have been surprised if he’d eventually pulled the plug on the whole filmmaking malarkey and walked away into the sunset, content to forever be known as the man who buried 20th Century Fox and ruined the careers of a plethora of unknown actors. After all, budgetary constraints, technological constraints, and a lack of belief in the project by almost all involved led to him nearly giving up many times during production.

Imagine, you’re a big time film producer, responsible for handing over millions of studio dollars to filmmakers to create works of art. A young man comes to you, dreaming of making a big-budget sci-fi opera, filled with robots, strange knights known as Jedi, walking carpet-men and a mystical old man who teaches a young boy about the Force. You’d laugh yourself to sleep every night, probably. And you’d send him on his way. The legend of Star Wars, the little sci-fi film that could, is probably the greatest example of cinematic gambling ever told: thank goodness Fox decided to fund Lucas’s vision, otherwise we’d probably not be talking about Star Wars right now. In the mid 70’s, science fiction was all the rage, especially within the comic and literary circles. The world ate up tales of invention, adventure, and science overcoming all and sundry. It was a world of hope and imagination, and a way for creative people to have a shot at foretelling the future, in a sense.

Along came George Lucas, his idea for a galaxy-spanning space saga already almost fully formed within his brain. A story about a young boy, orphaned and looked after by his Uncle on a desert planet, who is whisked away on an adventure to rescue a princess from the clutches of an evil warlord, who they must defeat in a last-gasp effort to destroy his magnificent space station. Entitled Star Wars, the script called for a bunch of weird and wacky creatures and cast members, a slew of new technology to engineer some of the most amazing effects required to get this story to the big screen, and a sense of belief in the fledgling director, who, up until that point, had not directed a major feature film. After being passed around to various studios, it was accepted by Fox when Lucas’ two script deal with Universal Studios was done. Lucas had just finished American Graffiti, for Universal, when Fox optioned the Star Wars script. Lucas, himself wanting to direct the movie, struggled to gain the trust of the major studio, but eventually they relented, and he was given a budget just over $8 million to make the film.

Production difficulties aside, which saw his predominantly British crew all but revolt against Lucas’ directorial authority, and the constant berating of his ability as a filmmaker, Lucas managed to craft the ludicrously weird screenplay into a final film, which confused a lot of people at the time it was made. Revolutionary special effects, models, a thunderous soundtrack by John Williams, and a cast of relative unknowns, all helped to make Star Wars a fairly innocuous entry into the cinematic year of 1977. Almost nobody took the film seriously, from inception to completion, although most of Hollywood would sit up when the film debuted in 77 and propelled Lucas to the position of one of the industry’s most celebrated ingenues.

The film opens with one of cinema’s most enduring visual cues: the Star Wars logo, and the famous theme from John Williams. Taking place, apparently, in a galaxy a long way away, and a very long time ago, a tiny spacecraft whizzes by, lasers flying past it, sometimes striking. Then, a thunderous bassline kicks in, followed by the roar of an enormous, white panelled starship, which fills the entire screen in the most jaw-dropping film openings of all time. The music continues to envelop us, the two spacecrafts slicing through space like knives, their respective laser fire flashing upon us and lighting up the screen. There’s a cacophony of noise, a cataclysmic shift in cinematic storytelling as this enormous living, breathing spacecraft comes to life. Soon, there’s a funny looking golden robot on screen, chatting animatedly to a smaller, wheeled robot which whistles and beeps like a dervish. A young woman, bent over the smaller robot, ducks away when danger appears to approach. She is captured, and is confronted by an ominous, black-suited man with asthma. She is now his prisoner, and apparently, she has plans that have been stolen.

Weird, unconventional, and without any explanation, we are given front-row seats in one of cinema’s greatest opening stanzas. Then, the film takes us to Tatooine, a desert planet where we meet Luke Skywalker, eponymous hero of the film, and his mysterious guardian, Obi-Wan Kenobi, an old man who seems to know more than he’s letting on. It’s like being thrown into a story and told to just run with it: we get no backstory, no explanation for what the heck is happening, and for some reason, we love it. Magic is happening before our very eyes. The simplicity of the story, the eloquence with which Lucas treats the material, and the complete lack of pandering to the audience (something which is refreshing, to be truthful) ensures that while we may not know what’s happening here, we are still emotionally caught up in the plight of our central cast. Luke and Obi-Wan, who tells Luke he is to become a Jedi Knight (a what then?) takes the boy to rescue the captures Princess Leia (she who was bent over the robot, and not in that way either, you clods!) from the space station she’s being held on. They meet up with Han Solo, a recalcitrant space pilot who offers to take them to where they need to go, and his first mate, Chewbacca, a gigantic shaggy-haired creature known as a Wookie. Boarding Han’s ship, the Millennium Falcon, they are whisked away to Alderaan, before discovering the planet has been destroyed by the evil Empire’s new space station, the Death Star. The Falcon is captured by the Death Star’s tractor beam, and thus, our intrepid heroes must not only rescue the princess, but turn off the tractor beam to escape.

Star Wars was unconventional from the outset. It’s world is primarily a dirty, battered universe of grimy creatures, militaristic ruling class, rundown technology and a sense of depression by the populace. A far cry indeed from the bright, shiny science fiction worlds espoused by films like Buck Rogers and 2001: A Space Odyssey. The Empire, the ruling party of the universe, and led by Darth Vader and assisted by General Tarkin (a wonderfully smooth Peter Cushing) have all but annihilated the resistance party who would seek to bring them down. Leia, herself a feisty princess who expects a lot, is on her way to the hideout of the resistance to help their cause, enlists the young Skywalker and soon, he finds himself in the sky above the Death Star seeking to destroy it. The themes within the film are almost universally understood: after all, who hasn’t wanted to be the hero of a story, which young girls hasn’t thought about being a princess, and which hairy man hasn’t wanted to be a Wookie? Most of us, I’d imagine. The imaginative power this film had upon a generation is profound to say the least. Many famous directors cite this film as being the catalyst for their own careers, something for which we can thank Mr Lucas.

It’s hard to try and criticise Star Wars, now retitled A New Hope in the aftermath of its successful sequels. Originally released simply as Star Wars, the film had to be reflective of the sequel titles such as The Empire Strikes Back and Return Of The Jedi, so was rebadged upon re-release in cinemas and on subsequent video/DVD releases. The reference of the hope is, of course, Luke Skywalker, portrayed quite convincingly by Mark Hamill, forever typecast by the iconic role. Luke represents the hope of defeat for the Empire, a somewhat cryptic link to the fact that he’s really Darth Vaders son, which would be revealed only in the immediate sequel. However, as far as fan’s could make out, the hope in the title represented a victory by the resistance to the Death Star, itself destroyed by Luke and Han in one of the great space battles of modern times. A New Hope is replete with great characters, among them Obi-Wan Kenobi, portrayed by Oscar Winner Alec Guinness, Harrison Ford’s laconic portrayal of Han Solo, and Carrie Fisher’s tiny (but bossy) Princess Leia. But by far the most iconic and enduring image of this film was that of black-garbed Darth Vader, the principal villain, and possessor of the mysterious energy known as the Force. In one of his early scenes, he all but strangles an officer by merely closing his fingers together in mid-air, the Force a tangible element that runs through the universe, as defined by Obi-Wan in an expository scene with Luke. Vader, his breathing augmented by machine, his body kept alive by the very suit he lives in, is the personification of evil in cinema. He’s malice personified, and a seemingly unstoppable force to be reckoned with.

The film has a kind of joyously cool, hip-smart dialogue, a sense of enjoyment within itself that’s hard to quantify. While the Empire is evil, and Luke and Obi-Wan face impossible odds, the sense of fun within the film is palpable, and often infectious. The dialogue, which is razor sharp and filled with great humour, accompanied with some memorable quotes that have since entered the pop-culture DNA (Use the Force Luke) is smartly written by Lucas, his screenplay a perfect blend of action and drama, sci-fi extravagance and a subtle, simple frugality: at no stage to we feel overawed by the story or characters, they manage to retain a humanity that we can attach to as viewers. We gain an empathy for them, even, to some degree, Vader, who in his final moments of battle with Obi-Wan, manages to hint of something larger at work, a history we are unaware of coming to fruition. There’s a sense of large-scale epic-ness to A New Hope, engendered by the cast and engineered perfectly by Lucas. You either get it, or you don’t. The story moves along at a cracking pace, never allowing itself to become bogged down by explanation or self importance. It’s a refreshing film, a casting off of old-style Hollywood clichés, engendering a zest and simplicity most films, especially the heavier ones, don’t quite match.

You have to remember, this is the first of the Star Wars films. It’s the first time we get to hear about the Force, see lightsabres, know about Jedi and Sith Lords, Millennium Falcons (which, in a small aside, remains the second coolest spacecraft ever devised, behind Doctor Who’s TARDIS!) and Death Stars. The concepts on display are epic, and intimate, in alternate levels. The special effects, for their time, were revolutionary, and to this day, are among the most complex real-live model work ever accomplished for a feature film. The models of the spaceships, in their incredible detail, allow for the film to maintain it’s battered realism throughout, unlike the Prequel Trilogy’s more CGI-ified world, which lacks the realism needed to keep the same tonality. The sight of the Millennium Falcon streaking through space between the almighty Star Destroyers of the Empire is an indelible image for me from this series. The world had never seen anything like it, and neither had I. It suddenly allowed us to imagine science fiction in a whole new way, and it somehow tapped into the Jedi in all of us. Suddenly, the impossible could be possible for the lowbrow among us: unlike the more convoluted upper-class sci-fi of Kubrick’s 2001, A New Hope gave us the lower class equivalent. A Lawrence Of Arabia for the socially downtrodden, if you will. Everybody could enjoy this film, the fanciful nature of the universe it eschewed allowed for all manner of experiences to be enjoyed: the villainous, the heroic, the diffident, the beautiful.

I’m going to be unable to criticise A New Hope here today, mainly because of the regard with which I hold the film generally. It’s one of my all-time favourite films, although not my most favourite of the Star Wars series. That honour goes to Return Of The Jedi. All I am willing to say about A New Hope is that it managed to unleash upon the world a new way of thinking about cinema: technologically, it uncorked the genie, in terms of advancements in cinematic form. It’s not a perfect film, by no means. It’s got it’s own issues, that’s for certain, that prevent it from reaching the zenith of the marking scale we award films here at at fernbyfilms.com. But A New Hope is not meant to be a perfect film. It’s meant to be a wonderful escapist treasure, a fantasy of the highest order designed to release us, for a couple of hours, from the drudgery of our own lives and live for a minute on a distant planet, in a spaceship, in a distant galaxy. We often dream of being a hero, being a princess (well, not me, per se, but you female readers out there!) or flying through space at the speed of light: thanks to A New Hope, we could finally live out that fantasy writ large.