Widescreen – Can I Get A Cream To Make It Go Away? – Part 1

What is 16×9? What’s the difference between DVD and Blu-ray, and what on earth does “1080p” mean? Which is better, LCD or Plasma television sets? Can I get rid of the black bars I see when I watch a DVD on my TV? What’s with that anyway?

I get asked these questions a fair bit, and I also hear them mentioned in general conversation a lot as well. As somebody who prides themselves on knowing a reasonable amount about film (and it’s associated trappings) I figured it would be helpful if I published a Small Words Manual of sorts to help explain all this new, confusing terminology and technology. In this 4 part series, each essay will tackle the common issues that are causing the most confusion, in an easy to understand format that makes sense, and not confuse the issue even further.

In Part 1, we’ll cover the basic history of cinema, the onset of widescreen in cinematic form, and how it transfers across to DVD.

*******************

Part 1 – A Short History of Cinema.

In the early part of the 20th Century, people began experimenting with a new film technology that allowed once still images to move. The age of cinema was born, and audiences flocked to movie houses to see this new scientific wonder.

By exposing sequential frames of a roll of film through a specially designed camera, and replaying that film back later through a special projector, the speed of the film frames across the light gave people the impression that the images were, indeed, moving.

In the heady days of burgeoning science, this was, of course, revolutionary. Nowadays, of course, we take film for granted. But back then, motion pictures were the newest and greatest form of entertainment.

As film-making technology improved, those with money to back the new enterprise found ways of creating a whole new industry to capture the publics interest and money. And so the movie industry was born.

As usual with a new technology, people began to experiment with it over time, creating new film stock (“stock” is the term used to describe the actual film used in the camera) to make the movie-going experience better. With the advent of sound, film took on a whole new level of entertainment, as people could now hear what the actors on screen actually sounded like. Cinema houses became a mecca for people escaping the humdrum and war torn life they were experiencing through the Great Depression, and both World Wars.

In the 50’s, however, a challenger to cinema came along in the form of television. This revolutionary technology allowed images to be broadcast right into a persons home, free of charge, almost 24 hours a day. A ferocious battle between cinema studios and television broadcasters (who, at the time, were not all owned by the same corporation) erupted for control of the publics imagination.

The decline of cinema attendances meant that the major studios had to look at ways of increasing their patronage, by making the cinema-going experience a more entertaining event than just sitting at home watching the latest comedy television show. Money was poured into film technology like never before, new projection systems, the addition of colour and the awesome new “widescreen” or “scope” presentation, by which the screen sizes were wider and taller than ever before. Stereophonic sound, providing better sound separation and fidelity, was slowly added, thus giving cinema audiences a more involving, epic experience.

In the “olden days” of cinema, often referred to as the Golden Age of the studio system, Hollywood was ruled by the big 5 studios of the day. Warner Bros, Fox Pictures (a forerunner of 20th Century Fox), Paramount Pictures, MGM Studios, and RKO Studios all ran a tightly controlled ship, contracting their staff and creative personnel in such ways that it stifled the industry behind a cloud of control and backstage animosity.

Universal and Columbia, both smaller studios, also ran under the studio system, but to a lesser extent. Actors were unable to appear in a Fox Studio’s film if they were, say, under contract to Warners. Directors were unable to make a project for Fox if they had a contract with RKO. This control exerted by the industry was compounded by the fact that each studio owned their own cinema houses, or at least a controlling stake in them, which meant they could dictate to owners what films to show and what not to.

During the 50s, however, a major court ruling against the Studio System meant that it was unfair under the trading laws for studios to own their own cinemas, and consequently, they had to relinquish this control. The breakdown of the Studio System also meant that directors, stars and other staffers could take contracts for anybody they desired, and this ended up with the system of Hollywood we know today.

Cinema and TV studios are now all owned by major corporations, most of whom are pretty closely tied together anyway. Studio’s have come and gone (MGM Studios are now a subsidiary of Sony Pictures, which also owns Columbia (and the Tri-Star Studio’s label) as well as TV production studio Sony Pictures Television), but Hollywood has survived throughout many turbulent years.

Part 2 – The Introduction of the Widescreen Process (aka: What is an “Aspect Ratio”?)

As mentioned above, to try and attract more viewers to their cinema’s in the face of television opposition, studio’s investigated the new “scope” cinematic format, that is, a large format widescreen film process by which cinema’s could display films on really wide screens, with larger and better sound quality.

Formats bandied about by studios were meant to inspire visions of grand epic films, with labels such as “Techniscope”, “Superscope”, “Cinerama” and others. While all labelled differently, they all amounted to the same thing: films shot with a large format film stock that provided a) greater resolution in image quality, and b) a wider image that allowed a more epic feel to the proceedings.

These wide images became larger and wider as time went by, as each studio wanted their own “widescreen” format to push onto the market.

A lot of these widescreen formats are now obsolete, as a standardised format was eventually settled upon as time went by. Using a special lens, known as an anamorphic lens, these wide images could be filmed onto a square (or almost square) film frame. This “Squeeze” effect is known as anamorphism, which, when played back in the cinema with an appropriate lens on the projector, appears nice and wide as normal (or unsqueezed).

The aspect of the frame was usually dependent on the lens used to capture said image. The aspect ratio is used by the film industry to standardize measurements in film stock and framing. You will usually see it written something like this: 2.35:1. With the last number being the unit of height, and the first number representing the width, this ratio will indicate to the viewer that the screen widthis 2.35 times as wide as it is high. It would follow that a film with a widescreen aspect of 1.85:1 would be almost twice as wide as high, although not quite.

This simple understanding of aspect ratio is pretty important to reproduction media such as DVD or Blu-ray Disc, which is used to play films in your home cinema. These aspect ratio formats will come back into play then.

First, though, let’s explore the different aspect ratios, which are relatively common on DVD these days.

1.33:1 – This is the original aspect ratio for feature film, and a ratio the Academy Of Motion Picture Art’s And Sciences calls Academy Ratio. The majority of films shot before 1950 use this ratio, which is essentially square. It’s this ratio that the old square televisions used to broadcast, which made it easy for films to fit onto TV screens during the early days.

1.66:1 – This aspect ratio is perhaps the most common aspect ratio used by early widescreen adopters, particularly Paramount Pictures and the Disney Studio. Stanley Kubrick shot most of his films in this aspect, which is also, very close in frame format to a squarish TV screen.

1.77:1 – This aspect is usually used as a standard for most High Definition television broadcasts. Some filmmakers will shoot a film in this aspect to ensure it can be screened on HD TV with no alteration in picture size. (More on this later).

1.85:1 – The most common aspect ratio used by Hollywood studios. Has replaced 1.33:1 as the default aspect for non-scope pictures.

2.35:1 (or 2.39:1) – The most common widescreen format in use today. Almost all “scope” pictures are filmed with this aspect.

2.55:1 – Extremely wide aspect ratio, used on several films in the 50’s and 60’s. Prime example of this is The Bridge On The River Kwai.

2.77:1 – Almost three times wider than it is high, this is the widest known single-camera aspect ratio ever utilised by the Hollywood system. Used to great effect on Charlton Heston’s Ben Hur, among others, this format was prohibitively expensive for cinema owners to install and make full use of. Only a small number for films were shot with this aspect ratio.

”]”]

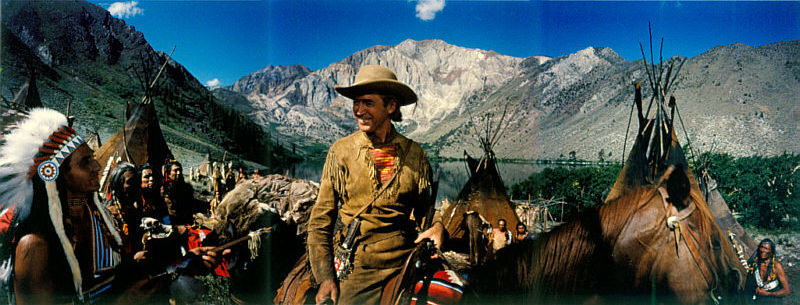

2.89:1 (Cinerama) – Cinerama is a film process by which three individual synchronised cameras filmed a sequence, and then the three images were spliced together next to each other, creating a superwide screen aspect. It was claimed that the film aspect had a ratio approximately 2.60:1 during filming, which could be expanded to 2.65:1 when displayed in the cinema. However, Warner Bros Studios claim their remastering effort on How The West Was Won is displayed in the widest known aspect, 2.89:1, so the point is contentious. In the above image, you can clearly see the three individually filmed images “spliced” together to form one single image. (Editors note: check out the different blue colours across the sky)

The image below is a diagram of the cinema experience of showing a Cinerama film. As you can see, three projectors are required to display the image on a deeply curved screen, which itself was required to counteract the distortion inherent in such a filming process.

IMAX – 70mm Film Format

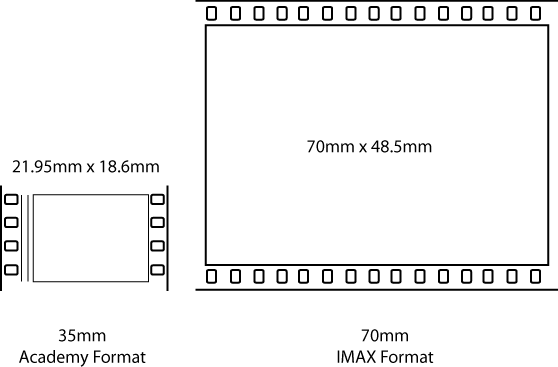

IMAX is a large gauge format film, similar in many ways to 70mm film, in that the film stock contains a higher “picture area” with which to work, allowing for resolution far superior to traditional 35mm cinema film. Unlike regular motion pictures using 70mm film, IMAX film stock is run through the camera sideways, allowing for a greater aperture to be used, resulting in crisper, sharper pictures.

Due to cost, IMAX feature length films are relatively uncommon, although shorter documentaries are shown in specially built cinema’s around the world. Some feature films are specifically designed for IMAX, such as Robert Zemeckis’ The Polar Express, and other films are shown in IMAX format on rare occasions.The space plane rescue sequence from Superman Returns was shown in some IMAX cinema’s in 3D, for example.

To give you an idea on the quality picture IMAX is capable of, the image below if a representation in the difference between standard 35mm film, and an IMAX frame. Note the larger area of the IMAX frame, allowing for substantially more detail to be captured during shooting.

We have now covered the issues of aspect ratios in cinematic terms, many of which will come to play in the home theatre market, involving DVD, Blu-Ray Disc and HD TV.

Part 3 – How Widescreen films look on DVD, and other matters like that.

In 1997, the first DVD’s were released onto the Australian market, to take the place of the VHS system in use at the time. Se7en, Priscilla Queen of The Desert, The Crow and one other I’ve forgotten were the original 4 released, and they were awful to see. Picture quality on those original disc’s was woeful, of course, given that the format and technology wasn’t quite up to scratch at that stage, but the mind boggled with just how useful the ability to store films on a medium that wasn’t as bulky as VHS tape would be.

Of course, uptake here in Australia for DVD, especially in light of niche disc format LaserDisc, was relatively slow compared to other markets (particularly the US) but eventually, the promulgation of product and machines to play these newfangled discs ensured that DVD was here to stay. Superb picture quality, coupled with stunning surround sound and lavish widescreen presentations gave film lover’s the added bonus of seeing their favourite films in a way they hadn’t done so since originally screened in cinemas.

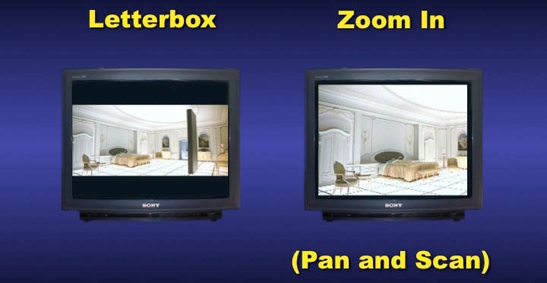

In the old day’s of VHS, widescreen film images (like the above 2.35:1 or wider) were “pan and scan” transferred onto VHS tape. Essentially, the image was cropped at the sides to ensure the entire square TV screen would be filled with picture. Of course, this cropping of the original picture image resulted in a substantial loss of information. Scenes originally shot in one frame, with an actor on each side of the screen, now had to be edited to show each actor at different moments, otherwise the viewer would loose track of what was happening. The use of pan/scan proliferated through the film industry when VHS became dominant, and continued right up until the death of the format recently. Most, if not all, film directors whose work had been butchered by these pan/scan edits of their films, decried this style of film presentation, as it took the dramatic impact of a scene and altered it somewhat, in most cases, lessening the impact of the scene overall.

In the above example, taken from the film Seven Brides For Seven Brothers, we can see the red square highlighting what a “full screen” version of the film would look like were it to be Pan/scanned onto VHS. The red square moves along the original film frame, resulting in a loss of side information, and even the elimination of characters completely from a shot. Everything outside the red square is lost on a square TV screen with the Pan/Scan process.

The best analogy I’ve heard for Pan/Scan is this: imagine if they’d simply hacked off the edges of the Mona Lisa to fit the first available frame they’d found lying about. That’s the artistic equivalent of pan/scan: hacking off the edges to suit the available screen size. The art world would obviously prefer “them” to find a frame to fit the painting, not the other way around. If you consider film to be an art-form, then the analogy is perfect.

With the advent of LaserDisc, film buffs had the ability to see films in their intended, or original, aspect ratio. OAR, as Original Aspect Ratio was known, became the norm for disc technology at the time, even though Pan/Scan VHS releases were more commercially viable.

The problem with showing a widescreen image on a square TV, for most people, were “the annoying black bars at the top and bottom of the screen”. You can’t fit an OAR rectangle into a square without leaving some space somewhere, and while viewer’s didn’t realise that they were being gypped by studios due to the re-editing of a film, most film-knowledgeable fans knew this, and hated the practice. The pan/scan process became known as Modified Aspect Ratio, or MAR, since the film was not being presented as the director intended.

On the release of DVD as a format, however, it was decided by the powers that be that films would be presented (at least, by major studios) in their OAR. Whether in 1.33:1 aspect as OAR, or 2.55:1 OAR, the formats adaptability enabled studios to present their films in the best possible way: the way it was meant to be seen. But the DVD industry faced an uphill battle for acceptance. People who had grown up with VHS pan/scan hack jobs didn’t know what those annoying black bars were for on new DVD releases. They wanted an image that filled their television screens, not some kind of freak show which DVD seemed to be presenting.

Slowly, however, education of the public managed to placate these fears, and once people realised that those back bars represented more visual information rather than less, DVD began to be accepted.

These days, all major HD & DVD releases by studios are with the original aspect ratio on the disc. With the advent of widescreen televisions, the resolution afforded on BluRay and DVD enabled the best possible sound and picture to be presented, ensuring that those who set themselves up with a surround sound speaker system also got the most accurate cinematic presentation right there in their own home.

Part 4 – What is Anamorphic Widescreen?

So, you get your DVD home to watch, and your brand new DVD player, all plugged in and ready to go. But when you pop it into the machine, the picture looks all funny. Like it’s been squashed somehow. Stretched and pulled in the wrong direction.

More often than not, a film will be “transferred” to DVD (that is, put onto the disc) in something known as “anamorphic” widescreen. What does this term mean, and how can I describe it in such a way that people lacking a degree in science engineering will understand?

First, the term anamorphic has changed meaning through the entire film industry into a multitude of meanings.

The original anamorphic meaning referred to the type of lenses directors used to attach to the front of film camera’s to capture an image. In the same way we use terms like “wide angle lens”, filmmakers used the term “anamorphic” to distinguish between flat film and those who used specialised lenses to achieve that wide format look.

Nowadays, while that term is still used by filmmakers, it’s more readily known by home cinema buffs as the way in which a picture image is presented on DVD. Due primarily to the large quantity of square, traditional televisions around the world, as well as the new technology of widescreen plasma’s and LCD’s, DVD manufacturers had to be savvy to the requirements of this newly forming technology.

For the sake of this article, we will simply be using the anamorphic term in its DVD styling.

DVD technology enables a large quantity of horizontal lines of information to be available for the presentation of a film. These horizontal lines are important in the reproduction of anamorphic video, compared with “letterbox” formats. Oh great, you think, he’s gone and used another term that I don’t understand.

Letterboxing derives it’s name from the fact that a 2.35:1 aspect ratio presented on a square screen looks substantially like a doorway mail slot; hence the term “letterbox”. There’s no more technical reason that that.

Therefore, when displaying a wide aspect ratio film on a square screen, it’s generically known as a letterbox format, with a minimal amount of horizontal lines of information displayed.

With a widescreen television, however, the fact that the wider screen more easily suits a widescreen image means that the full number of horizontal lines on offer in the image can be fully presented, without compromising the aspect ratio. This “anamorphism” technique means that a higher quality image can be presented on a widescreen television than on an older 4×3 one.

If you inspect the back of any DVD release on the shelf, at some point there will be a reference to “16×9” or “anamorphic transfer”, or something similar, which will indicate that to obtain the best possible picture image, the DVD should be viewed on a widescreen television screen.

The addendum to this, however, will occur with films originally shot in a 1.33:1 aspect ratio, which cannot be shown in a 16×9 format without compromising the image substantially. Conversely to a rectangle image being shown in a square screen, a square image cannot fit into a rectangular screen unless you crop the top and bottom of the original image.

In the case of a 1.33:1 aspect ratio film being screened on a widescreen TV, more often than not the image will be “pillar-boxed”, which means that black bars will be present at the left and right side of the screen, in order to preserve the square aspect ratio. In this case, the black bars look like pillars, hence the term being used.

If you have a digital set top box for either standard definition or high definition terrestrial TV broadcasts, you’ll be familiar with this practice, as most programmes filmed on TV before the introduction of TV widescreen are originally 1.33:1 aspect, and most TV stations pillar-box their broadcasts automatically to preserve the image on screen.

The nutshell thing to remember is this: an anamorphic DVD transfer is preferred in order to obtain the maximum amount of resolution on screen, regardless of screen size or aspect. The other thing to remember that those black bars you see on a widescreen television indicates that the film was shot in a really wide aspect ratio, and doesn’t mean you’re missing any information from the film. In actuality, you’re seeing the film the way the director intended, so it stands to reason that this would be the best way to watch.

*****************************

And so we conclude Part 1 of our series on widescreen and cinematic formats. In the next part, we turn our attention to the High Definition field, including the HD-DVD and BluRay Disc format war, the advent of HD television, and how this wave of the future will impact you and the way your kids live.

Still waiting for my Blu-ray player to arrive. It'll take a while because I haven't ordered it yet! But it's on my wish list of things to do now I have my new HD telly!

…but I'd be interested in seeing that Blu-ray at some point. I briefly studied film at university and the discussions of aspect ratio and how filmmakers have used the camera frame over the years always interested me. I'd love to see Lawrence of Arabia in its original format.

Man, we'd all love to see LOA in HD on Blu – the last DVD release I saw of it featured the restored version in OAR overseen by Robert Harris (he who writes for the prestigious Home Theatre Forum) was absolutely stunning in 720 format, one can only imagine seeing it on HD. Heck, I'd go see it in a cinema if anybody in Adelaide actually managed to snag a copy of the restored version! Imagine that stunning score in full lossless sound! Oh man, I'm drooling just thinking about it!

Brilliant article Rodney! I've certianly learnt a thing or two – especially about the Cinerama 2.89:1 format and how it was filmed. I've never seen How The West was Won but I wouldn't mind checking out the film with the Cinerama format in all its glory. Doubt there's many of those prints doing the rounds though.

There's no prints here in Australia, and doubtful there's any in England either – but the BluRay version of the film does a splendid job of replicating the film in both its original "curved" format ratio, and in a more traditionally presented 2.89:1 aspect as well. Can I suggest grabbing hold of the BluRay version, which includes a great documentary on the Cinerama process as well!!

Awsome article. I've linked to it on my "Links" page.

Keep up the good work.

Tony Hurd

Aspect Ratio Police (.com)

Cool site you have there Tony! When I get a moment over the weekend, I'll do up a link in return!